I have always been a big proponent of filtered (or dry stack) tailings over conventional tailings disposal. Several years ago I had written a blog (Fluid Tailings – Time to Kick The Habit?) that this is the tailings disposal approach the mining industry should be moving toward.

Recently I have been seeing more mining studies proposing to use the dry stack approach. In some cases, they no longer even do the typical tailings trade-off study that look at different options. The decision is made upfront that dry stack is the preferred route due to its environmental acceptability and positive perceptions.

Recently I have been seeing more mining studies proposing to use the dry stack approach. In some cases, they no longer even do the typical tailings trade-off study that look at different options. The decision is made upfront that dry stack is the preferred route due to its environmental acceptability and positive perceptions.

Recently I came across a nice document prepared by BHP and Rio Tinto titled “Filtered Stacked Tailings – A Guide for Study Managers (March 2024)”. I will refer to this document as “The Guide”. You should definitely get a copy of this Guide if your project is considering a dry stack operation. An information link is included at the end of this post.

A Guide for Study Managers

The Guide covers several topics, including tailings characterization; site closure concepts; filtered tailings stack design; material transport, stacking systems; and tailings dewatering methods. The Guide covers all the basics very well. The one area that jumped out at me is the tailings characterization and testing aspect.

The Guide covers several topics, including tailings characterization; site closure concepts; filtered tailings stack design; material transport, stacking systems; and tailings dewatering methods. The Guide covers all the basics very well. The one area that jumped out at me is the tailings characterization and testing aspect.

Many assume that dry stack is simply filter, haul, dump, then walkaway. Its all very easy! However, in reality, the entire dry stack approach is complex.

One needs to be able to consistently dewater tailings from different ore types, then transport it under different climatic conditions, and then place and compact the tailings efficiently.

One also needs to be able to deal with plant upsets, when the filtered tailings don’t meet the optimal product specifications. So its not really that simple.

One of the chapters in the Guide details the different test work that should be done to understand the dry stack approach. The list of tests is a lot longer than I had envisioned. I previously knew some of the types of lab testing required, however the Guide outlines a very comprehensive list.

The Guide also categorizes the tests according to study stage, be it concept study, order of magnitude study, or Pre-Feasibility level. Interestingly, the concept study can rely mainly on published information. However, the more advanced mining studies require the lab testing of actual tailings material.

Testing Checklist

To help organize the complexity of testing, I have listed their suggested tests as to whether the test is related to material characterization, process characterization, or filtered product characterization. Each aspect serves a different purpose in understanding the workings of the filtered tailings approach. The engineer will decide at which study stage they wish to do each of the tests, or which of the them they actually need to do.

To keep the blog post brief, I am not describing the details for each test. Most geotechnical or process engineers will already be familiar with them, or anyone can search the web to learn more.

MATERIAL CHARACTERIZATION TESTS

-

Chemical composition Testing: using atomic absorption or spectroscopy, identify the elements within the tailings stream to highlight contaminants and potential flocculation issues.

-

Conductivity Test: increase knowledge of the tailings stream.

-

Mineralogy Testing: identify mineral types and clay minerals (if any) that could impact on performance.

-

Particle Shape Analysis: are there fibrous minerals present, as well as settling and rheology effects.

-

Particle Size Distribution: are the tailings coarse, or mainly fine silt and clay sized particles that can impact on filtering and product performance.

-

pH Test: determine the acidity of the tailings steam, can relate to flocculant selection.

-

Tailings Slurry Density Test: assess the pumpability and amount of thickening and filtering that will be required.

-

Tailings Solid Mass Concentration and Moisture content: required for process mass balances.

-

Specific Gravity Testing: assess the SG of the tailing particles, i.e. light or heavy minerals.

-

Total Dissolved Solids Test: assess the fluid composition, are minerals dissolvable.

-

Zero Free Water Test: relates to the solids concentration at which the sample is fully saturated and may relate to transportability.

PROCESS CHARACTERIZATION TESTS

-

Total Suspended Solids: assess the quality of the return water from thickening or filtration.

-

Drained and Undrained Settling Test: to assess the thickening aspects and stack performance.

-

Setting Cylinder Tests: used to assess thickener settling performance.

-

Raked Setting Cylinder Tests: used to assess thickener settling performance.

-

Dynamic Continuous Settling Tests: used to assess thickening under continuous feed situation.

-

Minimum Moisture Content: assess the minimum moisture content achievable in filtration.

-

Vacuum/Pressure Filtration Test: often done by vendors, assess the filtering performance.

-

Compression Rheology: design consolidation / permeability data for filtering and disposal design.

-

Shear Rheology: provide information for pump and pipeline design.

-

Shear Yield Stress: provide processing insights for slurry dispersion and flocculation.

FILTERED PRODUCT CHARACTERIZATION TESTS

-

Leaching Tests (long term): assess whether the tailings stack will continue to leach metals and contaminants over the long term.

-

Leaching Tests (short term): assess whether the tailings stack will rapidly leach metals and contaminants.

-

Acid Base Accounting Tests: will the stack be an ARD concern.

-

Net Acid Generation: relates to ARD and neutralizing potential.

-

Air Drying Tests: determine the rate of natural air drying and dry density.

-

Atterberg Limits Testing: determine the plastic limit, liquid limit with respect to moisture content and stackability.

-

Consolidation Tests (one-dimensional): to assess the consolidation and settlement of the stack over time.

-

Proctor Density Tests: assess the optimal compacted density and moisture content vs the moisture content delivered by filtration.

-

Critical Void Ratio Tests: assess compaction, consolidation, and liquefaction potential.

-

Shear Testing: determine the geotechnical strength of the filtered product for stack height design.

-

Permeability Testing: assess the internal drainage characteristics of the filtered product.

-

Soil-water characteristics Tests: assess the unsaturated behavior of the filtered product.

-

Flow Moisture Point Tests: assess how well the material can be transported and placed.

-

Conveyance Testing: assess how well the material can be conveyed (troughing, steepness).

-

Minimum Angle for Discharge: used in the design of hoppers and chutes.

-

Angle of Repose Tests: used in hopper design and dry stack design. Ground Bearing Pressure: used to assess the trafficability of the deposit.

Conclusion

A dry stack operation might be just as complex as conventional tailings disposal, although that might not be the perception. Certainly, the processing side of filtered tailings is more complex than conventional tailings. The transportation design may also be more complex, as is the tailings placement methodology. The main complexity missing from the dry stack is the need for a large sludge retaining dam, albeit that is a huge and important difference.

Some might view the suggested testing checklist as overkill and decide that not all test work is necessary. That is most likely true for some situations, especially for small mines not dealing with large quantities of tailings. However for a project with a high capital investment, one doesn’t want to see the entire mill off-line because the tailings disposal system isn’t functioning.

Major miners, such as BHP and Rio Tinto, typically spare no expense on material testing for metallurgical or geotechnical purposes. They have the funds available to test and engineer to a high level to adequately de-risk the project to meet their investment thresholds.

Major miners, such as BHP and Rio Tinto, typically spare no expense on material testing for metallurgical or geotechnical purposes. They have the funds available to test and engineer to a high level to adequately de-risk the project to meet their investment thresholds.

Junior miners often don’t have the time or funds to spend on such comprehensive testing programs. “Good enough” is often good enough.

One reason why junior miners sign 5-year JV deals with the Major is the amount of technical work required to properly evaluate a project.

The Major understands the amount of time needed for sample collection, testing, analysis of results, and follow up with more testing. It takes a fair bit of time to reach a comfort level for moving forward. Even then, there are no guarantees of success.

Each tailings disposal project is unique in size, location, type of mineralization, site layout, and throughput rate, so each company must decide what level of testing is “good enough” to address their risk tolerance.

For those that would like to get a copy of the the Guide, you can find more information at this LinkedIn link. I thank BHP and Rio Tinto for putting their heads (and wallets) together to prepare (and share) this document.

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some.

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some. The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates.

The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates. ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen.

ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen. Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times. Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant.

Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant. Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate. These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers. There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work.

There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work. Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type.

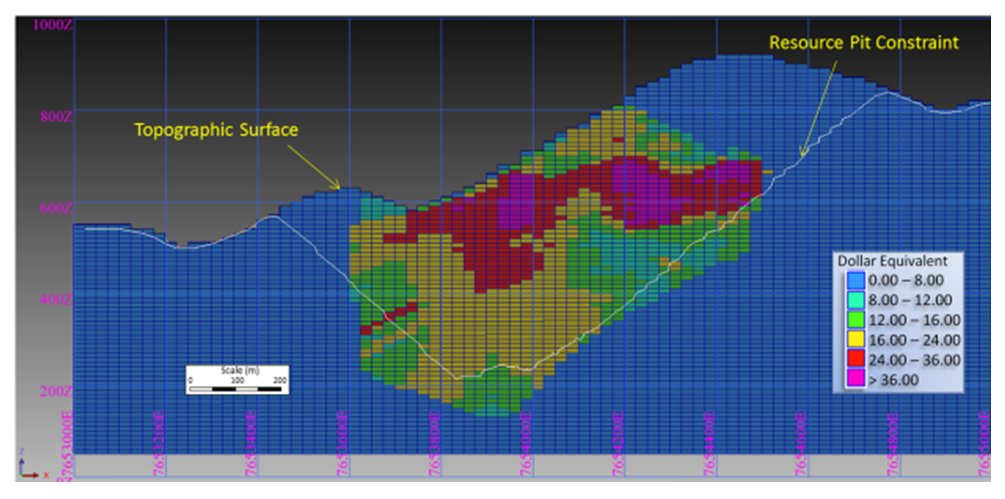

Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type. Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal.

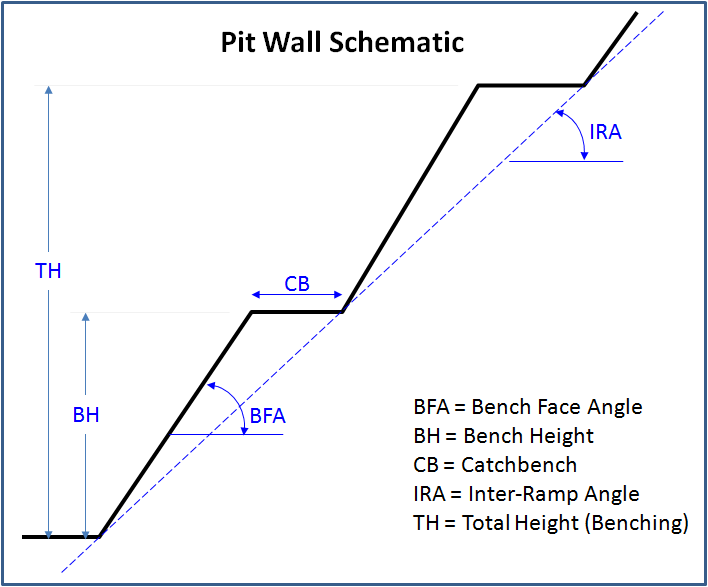

Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal. The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created. This ends Part 1. In Part 2 we will discuss the mining engineer’s next tasks; production scheduling; waste dump design; and equipment selection. The mining engineer QP will sign off and take responsibility for all the mine design work done so far. You can read Part 2 at this link “

This ends Part 1. In Part 2 we will discuss the mining engineer’s next tasks; production scheduling; waste dump design; and equipment selection. The mining engineer QP will sign off and take responsibility for all the mine design work done so far. You can read Part 2 at this link “

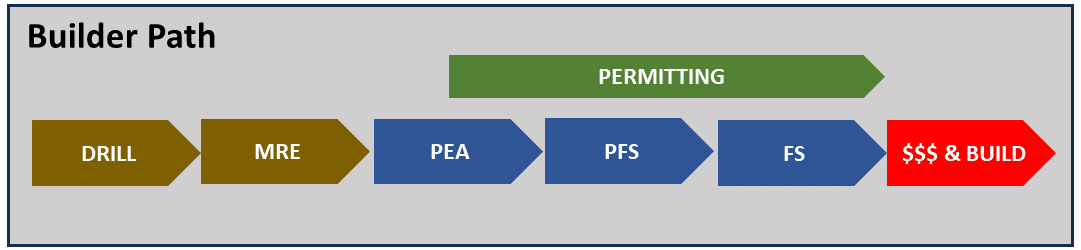

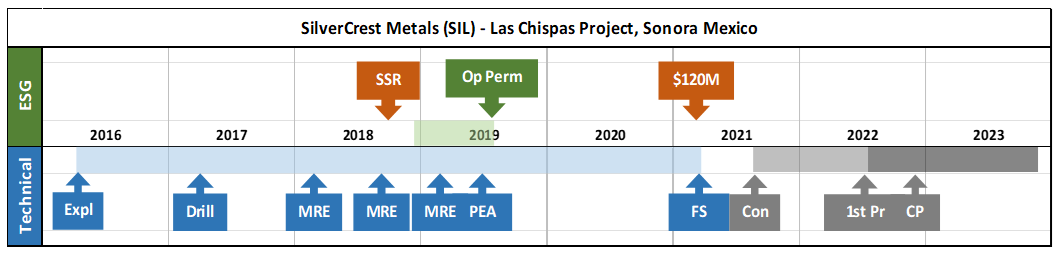

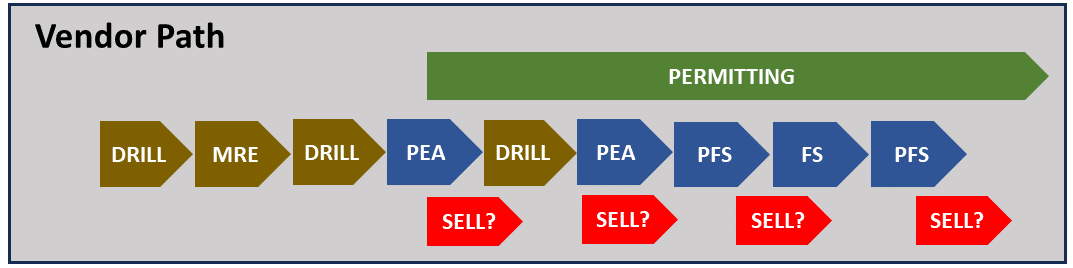

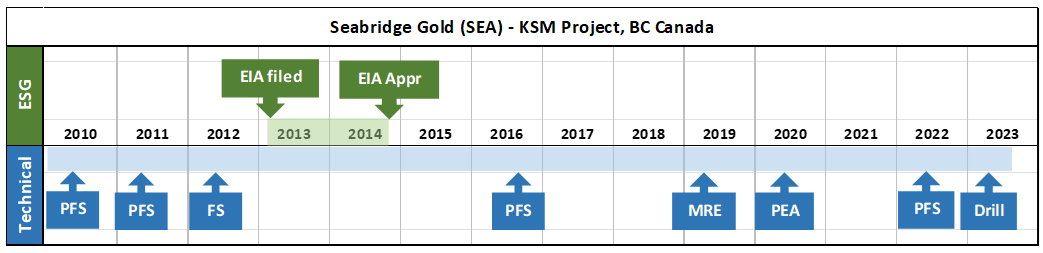

If an engineer understands that a Mine Builder’s project will move from PEA to PFS to FS in rapid succession, then there is more incentive to ensure each study is somewhat integrated.

If an engineer understands that a Mine Builder’s project will move from PEA to PFS to FS in rapid succession, then there is more incentive to ensure each study is somewhat integrated. As an engineer, it is helpful to understand the objectives of the project owner and then tailor the technical studies to meet those objectives. This does not mean low balling costs to make the study a promotional tool. It means focusing on what is important. It means recognizing the path, and what doesn’t need to be engineered in detail at this time. This may save the client time, money, and improve credibility in the long run.

As an engineer, it is helpful to understand the objectives of the project owner and then tailor the technical studies to meet those objectives. This does not mean low balling costs to make the study a promotional tool. It means focusing on what is important. It means recognizing the path, and what doesn’t need to be engineered in detail at this time. This may save the client time, money, and improve credibility in the long run. This post is just a brief discussion of mining project timelines. For those interested, there a few additional project timelines for curiosity purposes. Each path is unique because no two mining projects are the same. You can find these examples at this link “

This post is just a brief discussion of mining project timelines. For those interested, there a few additional project timelines for curiosity purposes. Each path is unique because no two mining projects are the same. You can find these examples at this link “

NPV One is targeting to replace the typical Excel based cashflow model with an online cloud model. It reminds me of personal income tax software, where one simply inputs the income and expense information, and then the software takes over doing all the calculations and outputting the result.

NPV One is targeting to replace the typical Excel based cashflow model with an online cloud model. It reminds me of personal income tax software, where one simply inputs the income and expense information, and then the software takes over doing all the calculations and outputting the result. Pros

Pros Like anything, nothing is perfect and NPV may have a few issues for me.

Like anything, nothing is perfect and NPV may have a few issues for me. The NPV One software is an option for those wishing to standardize or simplify their financial modelling.

The NPV One software is an option for those wishing to standardize or simplify their financial modelling.

I remember in the late fall of that year, the company had a chance to bid on a larger project in Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland. So our President, Frank Nolan (he was a brother to Fred Nolan, the infamous land-owner at Oak Island, by the way), decided he wanted to see the site and he chartered a Bell 106 helicopter to fly us there from Deer Lake. It was December (they say “December month” in that province) and when we got close to the Park, we ran into a sudden snow squall.

I remember in the late fall of that year, the company had a chance to bid on a larger project in Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland. So our President, Frank Nolan (he was a brother to Fred Nolan, the infamous land-owner at Oak Island, by the way), decided he wanted to see the site and he chartered a Bell 106 helicopter to fly us there from Deer Lake. It was December (they say “December month” in that province) and when we got close to the Park, we ran into a sudden snow squall. The QMM field office In Port Dauphin, Madagascar was located near the edge of town, and I typically walked from my lodging to the office each morning when I was there, about the time when school started for the children. Typically I passed dozens and dozens of tiny bamboo huts with corrugated metal roofs, and dirt floors each about 2 meters square.

The QMM field office In Port Dauphin, Madagascar was located near the edge of town, and I typically walked from my lodging to the office each morning when I was there, about the time when school started for the children. Typically I passed dozens and dozens of tiny bamboo huts with corrugated metal roofs, and dirt floors each about 2 meters square. It is one thing to briefly visit a remote project as part of a review team. It is another thing to be there as part of a design team trying to solve a problem and engineer a solution. I know of many engineers and geologists that would have similar work life experiences as part of their careers. However John has taken the initiative to write it all down.

It is one thing to briefly visit a remote project as part of a review team. It is another thing to be there as part of a design team trying to solve a problem and engineer a solution. I know of many engineers and geologists that would have similar work life experiences as part of their careers. However John has taken the initiative to write it all down.

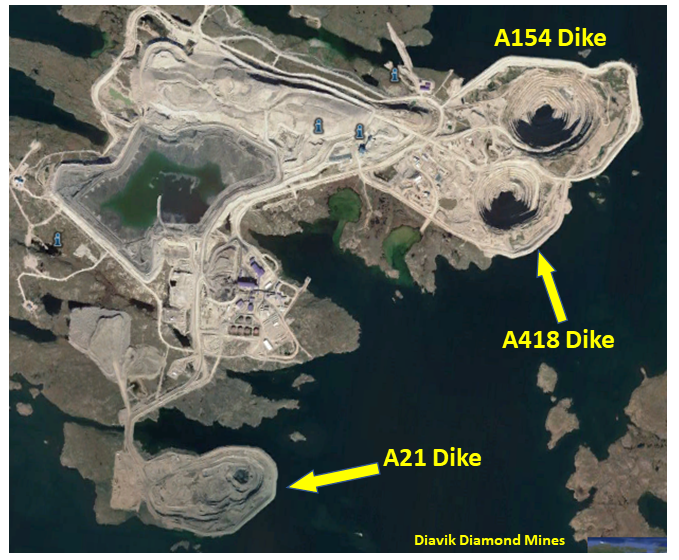

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction. There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project.

There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project. An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit.

An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit. Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time?

Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time? As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

This pessimism training started early in my career while working as a geotechnical engineer. Geotechnical engineers were always looking at failure modes and the potential causes of failure when assessing factors of safety.

This pessimism training started early in my career while working as a geotechnical engineer. Geotechnical engineers were always looking at failure modes and the potential causes of failure when assessing factors of safety. When undertaking a due diligence, particularly for a major company or financier, we are not hired to tell them how great the project is. We are hired to look for fatal flaws, identify poorly based design assumptions or errors and omissions in the technical work. We are mainly looking for negatives or red flags.

When undertaking a due diligence, particularly for a major company or financier, we are not hired to tell them how great the project is. We are hired to look for fatal flaws, identify poorly based design assumptions or errors and omissions in the technical work. We are mainly looking for negatives or red flags. It has been my experience that digging in a data room or speaking with the engineering consultants can reveal issues not identifiable in a 43-101 report. Possibly some of these issues were mentioned or glossed over in the report, but you won’t understand the full extent of the issues until digging deeper.

It has been my experience that digging in a data room or speaking with the engineering consultants can reveal issues not identifiable in a 43-101 report. Possibly some of these issues were mentioned or glossed over in the report, but you won’t understand the full extent of the issues until digging deeper. My hesitance in investing in some companies unfortunately can be penalizing. I may end up sitting on the sidelines while watching the rising stock price. Junior mining investors tend to be a positive bunch, when combined with good promotion can result in investors piling into a stock.

My hesitance in investing in some companies unfortunately can be penalizing. I may end up sitting on the sidelines while watching the rising stock price. Junior mining investors tend to be a positive bunch, when combined with good promotion can result in investors piling into a stock.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy. With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation.

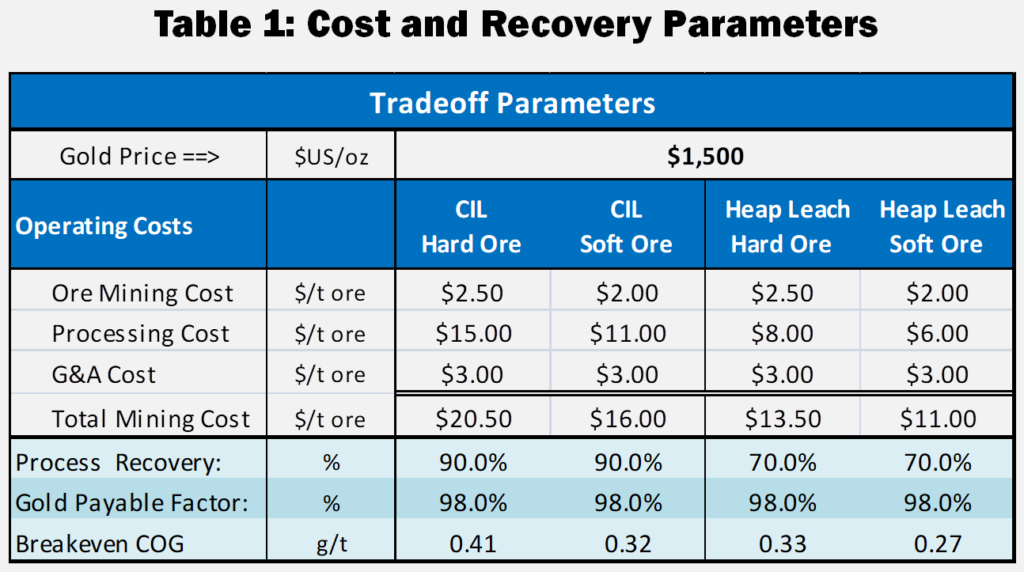

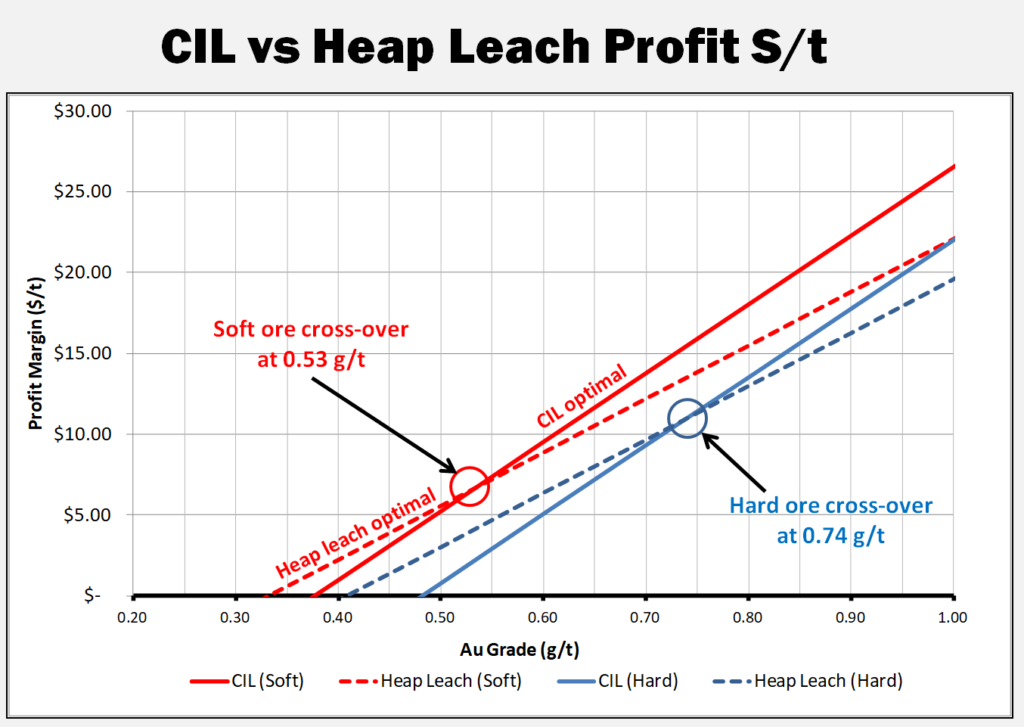

With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation. I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz.

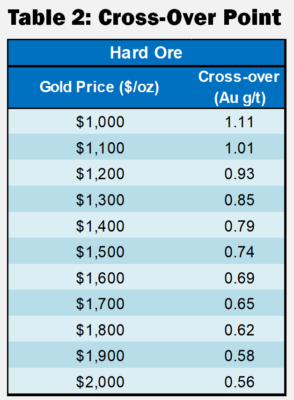

I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz. These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.