One of the first things we normally look at when examining a resource estimate is how much of the resource is classified as Measured or Indicated (“M+I”) compared to the Inferred tonnage. It is important to understand the uncertainty in the estimate and how much the Inferred proportion contributes. Having said that, I think we tend to focus less on the split between the Measured and Indicated tonnages.

Inferred resources have a role

We are all aware of the regulatory limitations imposed by Inferred resources in mining studies. They are speculative in nature and hence cannot be used in the economic models for pre-feasibility and feasibility studies. However Inferred resource can be used for production planing in a Preliminary Economic Assessment (“PEA”).

Inferred resources are so speculative that one cannot legally add them to the Measure and Indicated tonnages in a resource statement (although that is what everyone does). I don’t really understand the concern with a mineral resource statement if it includes a row that adds M+I tonnage with Inferred tonnes, as long as everything is transparent.

When a PEA mining schedule is developed, the three resource classifications can be combined into a single tonnage value. However in the resource statement the M+I+I cannot be totaled. A bit contradictory.

Are Measured resources important?

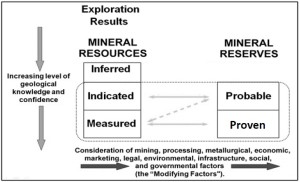

It appears to me that companies are more interested in what resource tonnage meets the M+I threshold but are not as concerned about the tonnage split between Measured and Indicated. It seems that M+I are largely being viewed the same. Since both Measured and Indicated resources can be used in a feasibility economic analysis, does it matter if the tonnage is 100% Measured (Proven) or 100% Indicated (Probable)?

The NI 43-101 and CIM guidelines provide definitions for Measured and Indicated resources but do not specify any different treatment like they do for the Inferred resources.

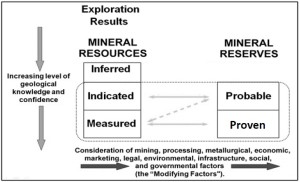

Relationship between Mineral Reserves and Mineral Resources (CIM Definition Standards).

Payback Period and Measured Resource

In my past experience with feasibility studies, some people applied a rule-of-thumb that the majority of the tonnage mined during the payback period must consist of Measure resource (i.e. Proven reserve).

The goal was to reduce project risk by ensuring the production tonnage providing the capital recovery is based on the resource with the highest certainty.

Generally I do not see this requirement used often, although I am not aware of what everyone is doing in every study. I realize there is a cost, and possibly a significant cost, to convert Indicated resource to Measured so there may be some hesitation in this approach. Hence it seems to be simpler for everyone to view the Measured and Indicated tonnages the same way.

Conclusion

NI 43-101 specifies how the Inferred resource can and cannot be utilized. Is it a matter of time before the regulators start specifying how Measured and Indicated resources must be used? There is some potential merit to this idea, however adding more regulation (and cost) to an already burdened industry would not be helpful.

Perhaps in the interest of transparency, feasibility studies should add two new rows to the bottom of the production schedule. These rows would show how the annual processing tonnages are split between Proven and Probable reserves. This enables one to can get a sense of the resource risk in the early years of the project. Given the mining software available today, it isn’t hard to provide this additional detail.

Note: If you would like to get notified when new blogs are posted, then sign up on the KJK mailing list on the website. Otherwise I post notices on LinkedIn, so follow me at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kenkuchling/.

Recently we have seen a trend of higher cash costs at operating mines when commodity prices are high. Why is this?

Recently we have seen a trend of higher cash costs at operating mines when commodity prices are high. Why is this?Do the opposite

Different companies have different corporate objectives and each mining project will be unique with regards to the impacts of cutoff grade changes on the orebody.

Different companies have different corporate objectives and each mining project will be unique with regards to the impacts of cutoff grade changes on the orebody.

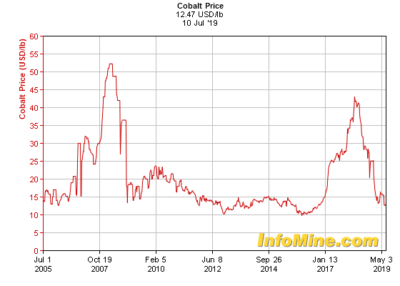

It seems that as soon as there is a price spike or positive market narrative, a commodity specific projects can take on a life of their own. The following list gives a few examples and, when you reflect upon them, ask how many actually came into successful production. These events occur at different times in different economic cycles.

It seems that as soon as there is a price spike or positive market narrative, a commodity specific projects can take on a life of their own. The following list gives a few examples and, when you reflect upon them, ask how many actually came into successful production. These events occur at different times in different economic cycles.

We have all seen the staking rushes that occur when a world class prospect is discovered. I’m sure we can all recall getting the large claim maps (as shown) with their multicolored graphics showing the patchwork of acquisitions around a discovery. PDAC was great for distributing these. They were well done and interesting to study.

We have all seen the staking rushes that occur when a world class prospect is discovered. I’m sure we can all recall getting the large claim maps (as shown) with their multicolored graphics showing the patchwork of acquisitions around a discovery. PDAC was great for distributing these. They were well done and interesting to study. Even mining or processing technologies could get caught up in somewhat of a wave and become a fad for further study. Sometimes this is driven by suppliers or consultants. For the engineers out there, who can recall…

Even mining or processing technologies could get caught up in somewhat of a wave and become a fad for further study. Sometimes this is driven by suppliers or consultants. For the engineers out there, who can recall…

The term Theory of Constraints may be common to some. However that concept is different than what is being discussed in the book. The TOC essentially relies on managing a constraint or eliminating it, and then addressing the next constraint in sequence.

The term Theory of Constraints may be common to some. However that concept is different than what is being discussed in the book. The TOC essentially relies on managing a constraint or eliminating it, and then addressing the next constraint in sequence.

The tech start-up model is similar to the junior mining business model as it relates to early stage funding followed by additional financing rounds. One obvious difference is that mining mainly uses the public financing route (IPO’s) while the tech industry relies on private equity venture capital (VC’s).

The tech start-up model is similar to the junior mining business model as it relates to early stage funding followed by additional financing rounds. One obvious difference is that mining mainly uses the public financing route (IPO’s) while the tech industry relies on private equity venture capital (VC’s). My first experience with the tech industry was associated with the many after-hours networking meetings called “meetups”. They are held weeknights from 6 to 9 pm and consist of guest speakers, expert panels, and for general networking purposes. Often guest speakers will describe their learnings in starting new companies and failures they had along the way.

My first experience with the tech industry was associated with the many after-hours networking meetings called “meetups”. They are held weeknights from 6 to 9 pm and consist of guest speakers, expert panels, and for general networking purposes. Often guest speakers will describe their learnings in starting new companies and failures they had along the way. Most of the tech meetups are held in local tech offices. These offices are great. They have an open concept, pool tables, ping pong, video games, fully stocked kitchen. Who wouldn’t want to work there?

Most of the tech meetups are held in local tech offices. These offices are great. They have an open concept, pool tables, ping pong, video games, fully stocked kitchen. Who wouldn’t want to work there? In the late 1990’s I was working in the Diavik engineering office in Calgary. They provided a unique office layout whereby everyone had an “office” but no front wall on the office so you couldn’t shut yourself in. There were numerous map layout tables scattered throughout the office to purposely foster discussion among the team.

In the late 1990’s I was working in the Diavik engineering office in Calgary. They provided a unique office layout whereby everyone had an “office” but no front wall on the office so you couldn’t shut yourself in. There were numerous map layout tables scattered throughout the office to purposely foster discussion among the team.

Irrespective of 43-101, if you are working at a mining operation the last thing you want to do is present management with an incorrect reserve, pit design, or production plan.

Irrespective of 43-101, if you are working at a mining operation the last thing you want to do is present management with an incorrect reserve, pit design, or production plan. As a QP, I suggest the onus is on the software developers to demonstrate that they can produce reliable and comparable results under all conditions. They need to be able to convince the future users that their software is accurate.

As a QP, I suggest the onus is on the software developers to demonstrate that they can produce reliable and comparable results under all conditions. They need to be able to convince the future users that their software is accurate.

So there likely is a significant network of experienced people out there. It’s just a matter of being able to tap into that network when someone needs specific expertise.

So there likely is a significant network of experienced people out there. It’s just a matter of being able to tap into that network when someone needs specific expertise.