There have been recent heap leach pad failures in the Yukon and Turkey and tailings dam failures in Chile and the Philippines. As a result I have been seeing more posts on LinkedIn about the application of satellite based InSAR deformation monitoring. Prior to that I had never heard of InSAR, so thought a little bit of background study might be worthwhile.

The following are my observations on what InSAR is and where it may be going. I am by no means an expert in this technology. I am merely viewing it from the perspective of a mine design engineer.

What is InSAR

InSAR is satellite-based “Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar”. It can measure the distance from a satellite to a ground feature. With repeated imaging it is used to detect changes in distance and measure displacements to within 5-10 millimetre accuracy. Hence it can be used as a potentially cost-effective slope monitoring tool, albeit it cannot be the only tool, as discussed later.

The relevant satellite images have been available for years. Currently the availability of analytical software to interpret the satellite data is improving. It can detect millimeter-scale displacements, however only in the line-of-sight (LOS) direction of the satellite. Using two or more satellites in different orbits, displacements in horizontal and vertical directions can be defined.

An example of a satellite being used is the Sentinel-1, launched in mid-2015 by the European Space Agency. This satellite information is open-source data. It will have a 6 to 12 day revisit cycle in many locations.

An example of a satellite being used is the Sentinel-1, launched in mid-2015 by the European Space Agency. This satellite information is open-source data. It will have a 6 to 12 day revisit cycle in many locations.

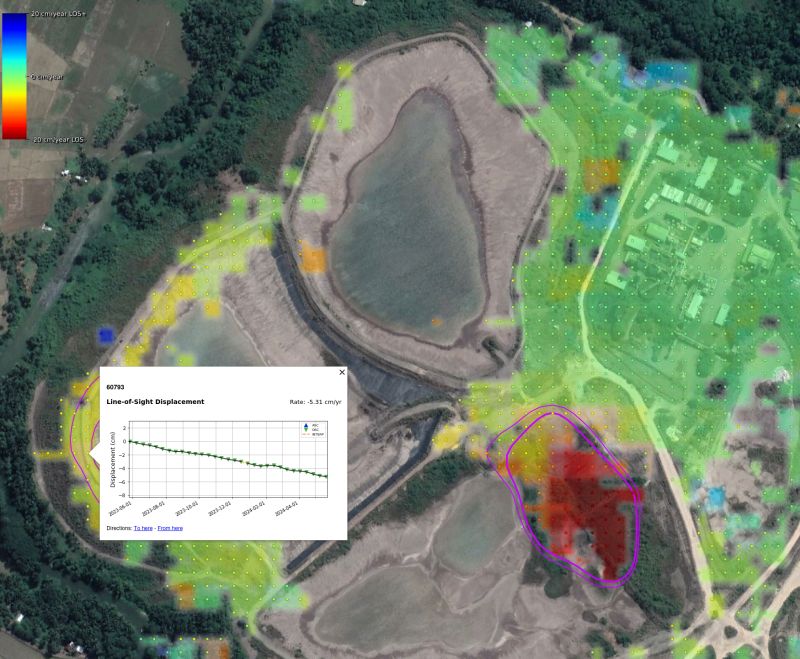

The results of an InSAR displacement survey are typically shown as a series of colored data points, typically coloured green for the stable points, trending to yellow and red for points that are moving.

This blog has some example images.

Some Limitations With InSAR

There are some limitations with InSAR, so it can only be part of a monitoring program. These limitations are:

-

The displacement direction is only measured in the direction of the satellite. Hence one may not know in which direction the movement is occurring. The magnitude of displacement could be underestimated depending on the apparent angle of measurement.

-

The movement being measured could consist of vertical settlement due to material consolidation and may not be horizontal and related to impending failure.

-

The displacement magnitude measured on opposite sides of a facility may have different accuracy, depending on the slope orientation versus the line-of-sight.

-

Areas with heavy vegetation may be difficult to monitor

-

Areas with heavy or persistent cloud cover can be difficult to monitor.

-

Areas with snow cover will be difficult to monitor.

-

The satellite return period may be weekly or every two weeks, so one is not able to analyze daily movements if a situation is critical. If the return visit day has cloud cover, there will be no new satellite data collected.

-

Areas with on-going construction or tailings deposition will lead to erroneous results.

-

Due to the line of sight, not all slope failure modes may be detectible (for example piping failure).

Regardless of these limitations, InSAR can still play a role in any monitoring program since it is able to monitor large areas quickly. Consider it as a pre-screening tool, being aware that not all failure modes may be detectible with it.

Discussion

On LinkedIn, one can see numerous posts where independent experts are examining historical InSAR data for recent failures to see whether early movement should have been detected. The results seem to be quite positive in that areas that have failed might have been red-flagged prior to failure.

On LinkedIn, one can see numerous posts where independent experts are examining historical InSAR data for recent failures to see whether early movement should have been detected. The results seem to be quite positive in that areas that have failed might have been red-flagged prior to failure.

There are also zones that showed critical displacements but have not failed.

Typically, there are four ways to monitor displacement in pit slopes, tailings dams, heap leach pads, and waste dumps. They are:

-

Insitu monitoring using embedded instruments, for example slope indicators, extensometers, and settlement gauges. These instruments provide information on what is happening internally within a slope, where actual movement is occurring, and they can be used in warning alert systems.

-

Surface monitoring using radar (ground based InSAR) systems and survey prisms. These tools measure only surface movements in selected areas, can be monitored as frequently as needed on an automated basis, and integrated into warning alert systems.

-

Drone or aerial surveys can be used to measure topography and monitor movements over large areas. This method requires a data processing delay (not real time) to derive the movement information, but such surveys can be done as frequently as needed.

-

InSAR from satellite can be used over very large regions to highlight areas with movement. That should trigger the implementation of one or more of the other monitoring approaches (if not already in place).

Conclusion

A mining site consists of numerous constructed embankments and slopes of all types and heights. Many of these slopes may be creeping and moving all the time – it’s a living beast.

A mining site consists of numerous constructed embankments and slopes of all types and heights. Many of these slopes may be creeping and moving all the time – it’s a living beast.

Recently I have been seeing more mining studies proposing to use the dry stack approach. In some cases, they no longer even do the typical tailings trade-off study that look at different options. The decision is made upfront that dry stack is the preferred route due to its environmental acceptability and positive perceptions.

Recently I have been seeing more mining studies proposing to use the dry stack approach. In some cases, they no longer even do the typical tailings trade-off study that look at different options. The decision is made upfront that dry stack is the preferred route due to its environmental acceptability and positive perceptions. The Guide covers several topics, including tailings characterization; site closure concepts; filtered tailings stack design; material transport, stacking systems; and tailings dewatering methods. The Guide covers all the basics very well. The one area that jumped out at me is the tailings characterization and testing aspect.

The Guide covers several topics, including tailings characterization; site closure concepts; filtered tailings stack design; material transport, stacking systems; and tailings dewatering methods. The Guide covers all the basics very well. The one area that jumped out at me is the tailings characterization and testing aspect. Major miners, such as BHP and Rio Tinto, typically spare no expense on material testing for metallurgical or geotechnical purposes. They have the funds available to test and engineer to a high level to adequately de-risk the project to meet their investment thresholds.

Major miners, such as BHP and Rio Tinto, typically spare no expense on material testing for metallurgical or geotechnical purposes. They have the funds available to test and engineer to a high level to adequately de-risk the project to meet their investment thresholds.

We hear a lot about the need for the mining industry to adopt sustainable mining practices. Is everyone certain what that actually means? Ask a group of people for their opinions on this and you’ll probably get a range of answers. It appears to me that there are two general perspectives on the issue.

We hear a lot about the need for the mining industry to adopt sustainable mining practices. Is everyone certain what that actually means? Ask a group of people for their opinions on this and you’ll probably get a range of answers. It appears to me that there are two general perspectives on the issue. The solutions proposed to foster sustainable mining depend on which perspective is considered.

The solutions proposed to foster sustainable mining depend on which perspective is considered. If one views sustainable mining from the second perspective, i.e. “What’s in it for us”, then one will propose different solutions. Maximizing benefits for the local community requires specific and direct actions. Generalizations won’t work. Stakeholder communities likely don’t care about the sustainability of the mining industry as a whole.

If one views sustainable mining from the second perspective, i.e. “What’s in it for us”, then one will propose different solutions. Maximizing benefits for the local community requires specific and direct actions. Generalizations won’t work. Stakeholder communities likely don’t care about the sustainability of the mining industry as a whole. There are teams of smart people representing mining companies working with the local communities. These sustainability teams will ultimately be the key players in making or breaking the sustainability of mining industry. They will build and maintain the perception of the industry.

There are teams of smart people representing mining companies working with the local communities. These sustainability teams will ultimately be the key players in making or breaking the sustainability of mining industry. They will build and maintain the perception of the industry.

Process water supply, water storage and treatment, and safe disposal of fine solids (i.e. tailings) are major concerns at most mining projects.

Process water supply, water storage and treatment, and safe disposal of fine solids (i.e. tailings) are major concerns at most mining projects. Electrostatic separation is a dry processing technique in which a mixture of minerals may be separated according to their electrical conductivity. The potash industry has studied this technology for decades.

Electrostatic separation is a dry processing technique in which a mixture of minerals may be separated according to their electrical conductivity. The potash industry has studied this technology for decades. The recovery of non-ferrous metals is the economic basis of every metal recycling system. There is worldwide use of eddy separators.

The recovery of non-ferrous metals is the economic basis of every metal recycling system. There is worldwide use of eddy separators. Given the contentious nature of water supply and slurried solids at many mining operations, industry research into dry processing might be money well spent.

Given the contentious nature of water supply and slurried solids at many mining operations, industry research into dry processing might be money well spent.

From time to time the Landslide Blog will examine mine slopes, tailings dams, and waste dump failures, however much of their information relates to natural earth or rock slopes along roads or in towns.

From time to time the Landslide Blog will examine mine slopes, tailings dams, and waste dump failures, however much of their information relates to natural earth or rock slopes along roads or in towns.

Environmental groups continually discuss ways of forcing regulators and mining companies to take action against the risk of tailings failure. This is commendable.

Environmental groups continually discuss ways of forcing regulators and mining companies to take action against the risk of tailings failure. This is commendable.