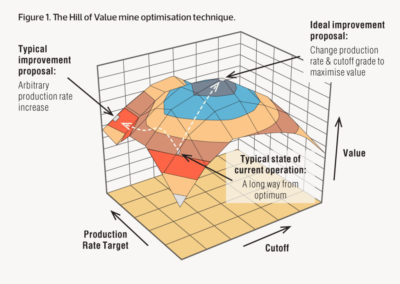

Recently I read some articles about the Hill of Value. I’m not going into detail about it but the Hill of Value is a mine optimization approach that’s been around for a while. Here is a link to an AusIMM article that describes it “The role of mine planning in high performance”. For those interested, here is a another post about this subject “About the Hill of Value. Learning from Mistakes (II)“.

(From AusIMM)

The basic premise is that an optimal mining project is based on a relationship between cut-off grade and production rate. The standard breakeven or incremental cutoff grade we normally use may not be optimal for a project.

The image to the right (from the aforementioned AusIMM article) illustrates the peak in the NPV (i.e. the hill of value) on a vertical axis.

A project requires a considerable technical effort to properly evaluate the hill of value. Each iteration of a cutoff grade results in a new mine plan, new production schedule, and a new mining capex and opex estimate.

Each iteration of the plant throughput requires a different mine plan and plant size and the associated project capex and opex. All of these iterations will generate a new cashflow model.

The effort to do that level of study thoroughly is quite significant. Perhaps one day artificial intelligence will be able to generate these iterations quickly, but we are not at that stage yet.

Can we simplify it?

In previous blogs (here and here) I described a 1D cashflow model that I use to quickly evaluate projects. The 1D approach does not rely on a production schedule, instead uses life-of-mine quantities and costs. Given its simplicity, I was curious if the 1D model could be used to evaluate the hill of value.

I compiled some data to run several iterations for a hypothetical project, loosely based on a mining study I had on hand. The critical inputs for such an analysis are the operating and capital cost ranges for different plant throughputs.

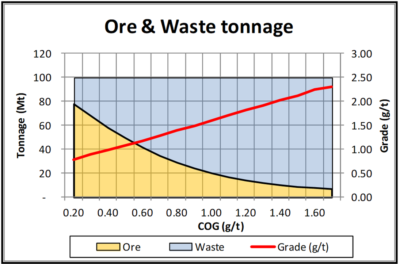

I had a grade tonnage curve, including the tonnes of ore and waste, for a designed pit. This data is shown graphically on the right. Essentially the mineable reserve is 62 Mt @ 0.94 g/t Pd with a strip ratio of 0.6 at a breakeven cutoff grade of 0.35 g/t. It’s a large tonnage, low strip ratio, and low grade deposit. The total pit tonnage is 100 Mt of combined ore and waste.

I had a grade tonnage curve, including the tonnes of ore and waste, for a designed pit. This data is shown graphically on the right. Essentially the mineable reserve is 62 Mt @ 0.94 g/t Pd with a strip ratio of 0.6 at a breakeven cutoff grade of 0.35 g/t. It’s a large tonnage, low strip ratio, and low grade deposit. The total pit tonnage is 100 Mt of combined ore and waste.

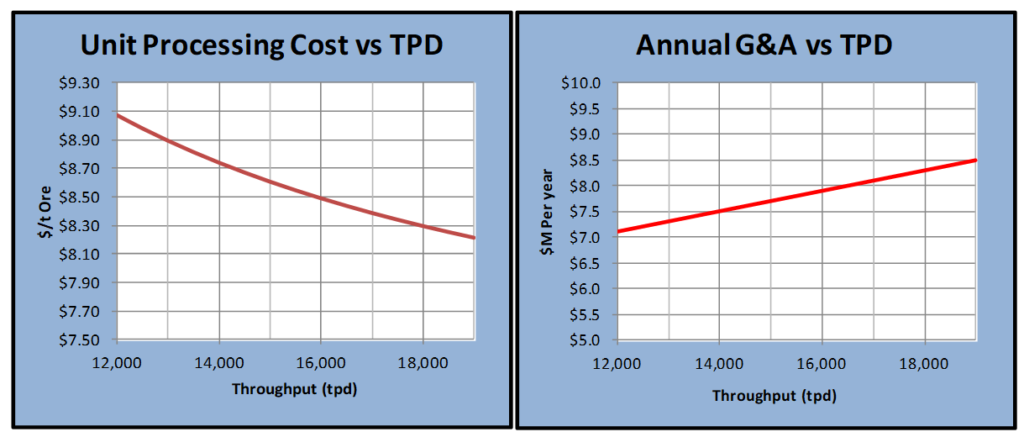

I estimated capital costs and operating costs for different production rates using escalation factors such as the rule of 0.6 and the 20% fixed – 80% variable basis. It would be best to complete proper cost estimations but that is beyond the scope of this analysis. Factoring is the main option when there are no other options.

The charts below show the cost inputs used in the model. Obviously each project would have its own set of unique cost curves.

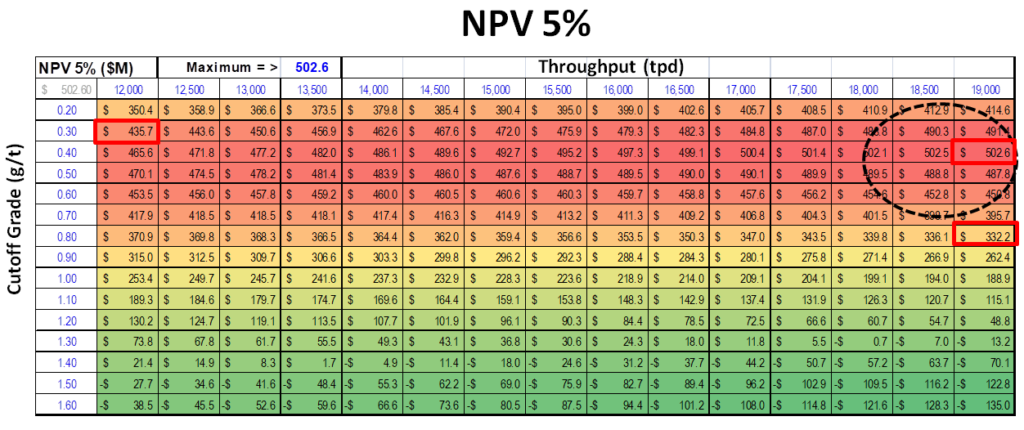

The 1D cashflow model was used to evaluate economics for a range of cutoff grades (from 0.20 g/t to 1.70 g/t) and production rates (12,000 tpd to 19,000 tpd). The NPV sensitivity analysis was done using the Excel data table function. This is one of my favorite and most useful Excel features.

A total of 225 cases were run (15 COG versus x 15 throughputs) for this example.

What are the results?

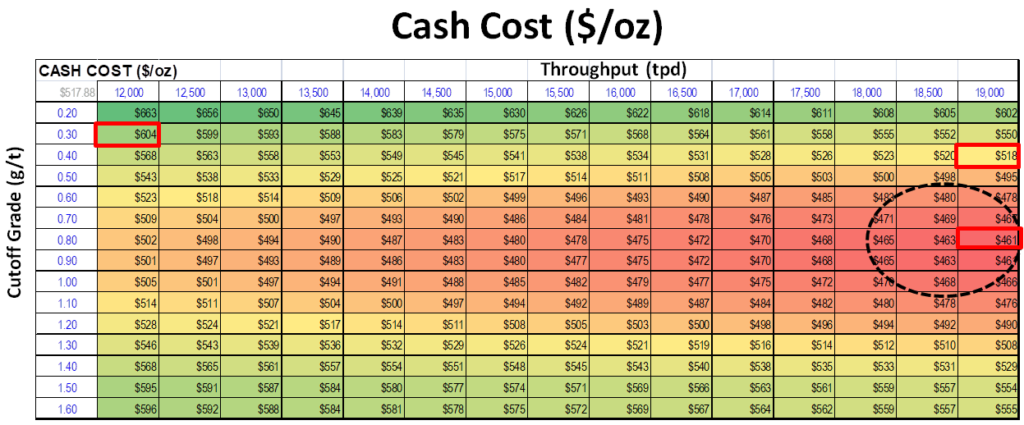

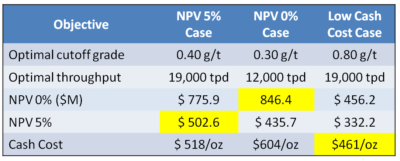

The results are shown below. Interestingly the optimal plant size and cutoff grade varies depending on the economic objective selected.

The discounted NPV 5% analysis indicates an optimal plant with a high throughput (19,000 tpd ) using a low cutoff grade (0.40 g/t). This would be expected due to the low grade nature of the orebody. Economies of scale, low operating costs, high revenues, are desired. Discounted models like revenue as quickly as possible; hence the high throughput rate.

The undiscounted NPV 0% analysis gave a different result. Since the timing of revenue is less important, a smaller plant was optimal (12,000 tpd) albeit using a similar low cutoff grade near the breakeven cutoff.

If one targets a low cash cost as an economic objective, one gets a different optimal project. This time a large plant with an elevated cutoff of 0.80 g/t was deemed optimal.

The Excel data table matrices for the three economic objectives are shown below. The “hot spots” in each case are evident.

Conclusion

The Hill of Value is an interesting optimization concept to apply to a project. In the example I have provided, the optimal project varies depending on what the financial objective is. I don’t know if this would be the case with all projects, however I suspect so.

The Hill of Value is an interesting optimization concept to apply to a project. In the example I have provided, the optimal project varies depending on what the financial objective is. I don’t know if this would be the case with all projects, however I suspect so.

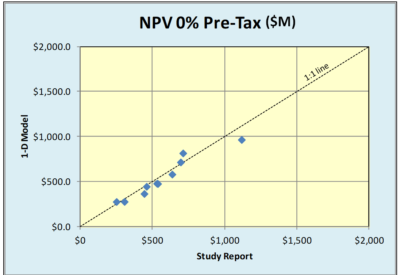

One of the questions I have been asked is how valid is the 1D approach compared to the standard 2D cashflow model. In order to examine that, I have randomly selected several recent 43-101 studies and plugged their reserve and cost parameters into the 1D model.

One of the questions I have been asked is how valid is the 1D approach compared to the standard 2D cashflow model. In order to examine that, I have randomly selected several recent 43-101 studies and plugged their reserve and cost parameters into the 1D model. There is surprisingly good agreement on both the discounted and undiscounted cases. Even the before and after tax cases look reasonably close.

There is surprisingly good agreement on both the discounted and undiscounted cases. Even the before and after tax cases look reasonably close.

Perhaps with technology, like Zoom, one can replicate the personal feel of a trade show booth. One can still have back and forth conversations with investors rather than just doing lecture style webinars.

Perhaps with technology, like Zoom, one can replicate the personal feel of a trade show booth. One can still have back and forth conversations with investors rather than just doing lecture style webinars. Management teams should introduce more than just the CEO or COO. Include VP’s of geology, engineering, corporate development, from time to time. Don’t hesitate to let the public meet more of your team. Trade show booths are often manned by different team members.

Management teams should introduce more than just the CEO or COO. Include VP’s of geology, engineering, corporate development, from time to time. Don’t hesitate to let the public meet more of your team. Trade show booths are often manned by different team members. Better communication with investors can increase confidence in a management team. Although some investors may not enjoy technical discussions, I think there is a subset that will find them very helpful and interesting. There will likely be an audience out there.

Better communication with investors can increase confidence in a management team. Although some investors may not enjoy technical discussions, I think there is a subset that will find them very helpful and interesting. There will likely be an audience out there. As an aside, if you are using Zoom make sure the host has configured the right settings. There are instances where anonymous participants can suddenly share their own computer screen, i.e. with questionable videos, to the group. It’s been referred to as “zoom bombing”.

As an aside, if you are using Zoom make sure the host has configured the right settings. There are instances where anonymous participants can suddenly share their own computer screen, i.e. with questionable videos, to the group. It’s been referred to as “zoom bombing”.

The number of independent mining consultants is increasing daily as more people reach retirement age or are made redundant.

The number of independent mining consultants is increasing daily as more people reach retirement age or are made redundant. GLG (

GLG ( Digbee (

Digbee (

We often see junior mining companies benchmarking themselves against others. Sometimes corporate presentations provide graphs of enterprise value per gold ounce to demonstrate that a company might be undervalued.

We often see junior mining companies benchmarking themselves against others. Sometimes corporate presentations provide graphs of enterprise value per gold ounce to demonstrate that a company might be undervalued. Lenders may have observers at site monitoring both construction progress and cash expenditures. Shareholders and analysts are watching for news releases that update the capital spending. Their concern is well founded due to several significant cost over-run instances.

Lenders may have observers at site monitoring both construction progress and cash expenditures. Shareholders and analysts are watching for news releases that update the capital spending. Their concern is well founded due to several significant cost over-run instances. It would be a good thing if the mining industry (or other concerned parties) work together to create open source project databases. These would incorporate summary information and cost information for global mining projects. The information is already out there, it just needs to be compiled.

It would be a good thing if the mining industry (or other concerned parties) work together to create open source project databases. These would incorporate summary information and cost information for global mining projects. The information is already out there, it just needs to be compiled. Benchmarking can be a great tool when done correctly. Benchmarking capital costs might bring more transparency to the project development process. It may help convince nervous investors that the proposed costs are reasonable.

Benchmarking can be a great tool when done correctly. Benchmarking capital costs might bring more transparency to the project development process. It may help convince nervous investors that the proposed costs are reasonable.

Reading it further, it was apparent that their study consultant, Ausenco, was being paid in company stock in lieu of cash. The arrangement included an initial financing of $750k with a further $375k to follow once the pre-feasibility study was 75% complete. Upon completion of the study another share payment was due.

Reading it further, it was apparent that their study consultant, Ausenco, was being paid in company stock in lieu of cash. The arrangement included an initial financing of $750k with a further $375k to follow once the pre-feasibility study was 75% complete. Upon completion of the study another share payment was due. I have never been in a situation where I was consulting with company shares as my compensation. Neither have I ever managed a study where outside consultants were being paid in shares. However I can see the possibility of interesting dynamics at play.

I have never been in a situation where I was consulting with company shares as my compensation. Neither have I ever managed a study where outside consultants were being paid in shares. However I can see the possibility of interesting dynamics at play. Regarding the first item “impartiality”, in the past there have been questions raised about the impartiality of engineering firms. I first recall reading this claim many years ago in a public response to a mining EIA application. Unfortunately I cannot find the exact source now.

Regarding the first item “impartiality”, in the past there have been questions raised about the impartiality of engineering firms. I first recall reading this claim many years ago in a public response to a mining EIA application. Unfortunately I cannot find the exact source now. It would be interesting to know how many consulting firms would be willing to accept compensation solely in shares. Stock prices move up and down and the outcome of the study itself can have an impact on share performance.

It would be interesting to know how many consulting firms would be willing to accept compensation solely in shares. Stock prices move up and down and the outcome of the study itself can have an impact on share performance.

In general to get financing and investor interest, development projects must demonstrate a high NPV, high IRR, and short payback period. This requirement tends to apply more to the small and mid tiered companies than to the major companies. The majors normally have different access to financing.

In general to get financing and investor interest, development projects must demonstrate a high NPV, high IRR, and short payback period. This requirement tends to apply more to the small and mid tiered companies than to the major companies. The majors normally have different access to financing. There are several scenarios where NPV analysis decision making may conflict with the objectives of sustainable mining. Here are a few examples.

There are several scenarios where NPV analysis decision making may conflict with the objectives of sustainable mining. Here are a few examples. 4. Low grade ore stockpiling can help to increase early revenue and profit, thereby improving the project NPV and payback. Stockpiling of low grade and prioritization of high grade means that lower grade ore will be processed in the later stages of the project life. Who hasn’t been happy to develop a mine schedule with the grade profile shown on the right?

4. Low grade ore stockpiling can help to increase early revenue and profit, thereby improving the project NPV and payback. Stockpiling of low grade and prioritization of high grade means that lower grade ore will be processed in the later stages of the project life. Who hasn’t been happy to develop a mine schedule with the grade profile shown on the right? 7. Accelerated depreciation, tax and royalty holidays are types of economic factors that will improve NPV and early payback. They are one tool governments use to promote economic activity. These tax holidays will greatly enhance the NPV when combined with high grading and waste stripping deferral.

7. Accelerated depreciation, tax and royalty holidays are types of economic factors that will improve NPV and early payback. They are one tool governments use to promote economic activity. These tax holidays will greatly enhance the NPV when combined with high grading and waste stripping deferral. NPV is one of the standard metrics used to make project decisions. The deferral of upfront costs in lieu of future costs is favorable for cashflow and investor returns. Similarly, increasing early revenue at the expense of future revenue does the same. Both approaches will help satisfy the financing concerns. However they may not be advantageous for creating long term sustainable projects.

NPV is one of the standard metrics used to make project decisions. The deferral of upfront costs in lieu of future costs is favorable for cashflow and investor returns. Similarly, increasing early revenue at the expense of future revenue does the same. Both approaches will help satisfy the financing concerns. However they may not be advantageous for creating long term sustainable projects.

We hear a lot about the need for the mining industry to adopt sustainable mining practices. Is everyone certain what that actually means? Ask a group of people for their opinions on this and you’ll probably get a range of answers. It appears to me that there are two general perspectives on the issue.

We hear a lot about the need for the mining industry to adopt sustainable mining practices. Is everyone certain what that actually means? Ask a group of people for their opinions on this and you’ll probably get a range of answers. It appears to me that there are two general perspectives on the issue. The solutions proposed to foster sustainable mining depend on which perspective is considered.

The solutions proposed to foster sustainable mining depend on which perspective is considered. There are teams of smart people representing mining companies working with the local communities. These sustainability teams will ultimately be the key players in making or breaking the sustainability of mining industry. They will build and maintain the perception of the industry.

There are teams of smart people representing mining companies working with the local communities. These sustainability teams will ultimately be the key players in making or breaking the sustainability of mining industry. They will build and maintain the perception of the industry.

I was at the 2019 Progressive Mine Forum in Toronto and a presentation was given on underground compressed air storage. The company was Hydrostor (

I was at the 2019 Progressive Mine Forum in Toronto and a presentation was given on underground compressed air storage. The company was Hydrostor (

Converting an abandoned mine into a power storage facility will still have its challenges. Cost and economic uncertainty are part of that. In addition, permitting such a facility will still require some environmental study.

Converting an abandoned mine into a power storage facility will still have its challenges. Cost and economic uncertainty are part of that. In addition, permitting such a facility will still require some environmental study.

It’s always open to debate who these 43-101 technical reports are intended for. Generally we can assume correctly that they are not being written mainly for geologists. However if they are intended for a wider audience of future investors, shareholders, engineers, and C-suite management, then (in my view) greater focus needs to be put on the physical orebody description.

It’s always open to debate who these 43-101 technical reports are intended for. Generally we can assume correctly that they are not being written mainly for geologists. However if they are intended for a wider audience of future investors, shareholders, engineers, and C-suite management, then (in my view) greater focus needs to be put on the physical orebody description. I would like to suggest that every technical report includes more focus on the operational aspects of the orebody.

I would like to suggest that every technical report includes more focus on the operational aspects of the orebody. Improving the quality of information presented to investors is one key way of maintaining trust with investors. Accordingly we should look to improve the description of the mineable ore body for everyone. In many cases it is the key to the entire project.

Improving the quality of information presented to investors is one key way of maintaining trust with investors. Accordingly we should look to improve the description of the mineable ore body for everyone. In many cases it is the key to the entire project.