Mosaic K1 Mine

Between 1985 and 1989 I worked at the Mosaic K1 potash mine in Saskatchewan, Canada. I had roles that included mine engineer, chief mine engineer and production foreman. This was relatively early in my work career so it represented an important learning period of time for me.

Each of these roles gave me a different perspective about a mining operation. In this two part blog, I’ll share some stories relating to the uniqueness of potash mining.

The K1 mine is 15 kilometres outside the town of Esterhazy; about 2.5 hours east of Regina. The mine is located at a depth of around 3,000 feet below surface, hence the title of this blog.

I will be referring to imperial units in this text because when the mine started production in the early 1960’s the maps and units were imperial and continued on through the 80’s. At my previous job with Syncrude we used metric units, so it took some time to mentally recalculate back.

Geologically, the province wide Esterhazy Member was being mined, named after the town. The layer was about 8 ft high. In other regions of Saskatchewan they are mining a different potash layer (the Patience Lake Member) which is located a few feet higher up. These mines have slightly different mining conditions than we experienced in Esterhazy. An example of their conditions is shown in the photo, where a parting layer can result in a roof collapse.

The Mosaic K1 and K2 mine shafts are interconnected at depth 6 miles. The total expanse of the K1 and K2 underground workings probably extends laterally over 18 miles. Back in the 80’s they said there were over 1,000 miles of tunnel underground and probably a lot more now since the mines are still operating. There is now a new K3 shaft which allows access to more distant potash reserves.

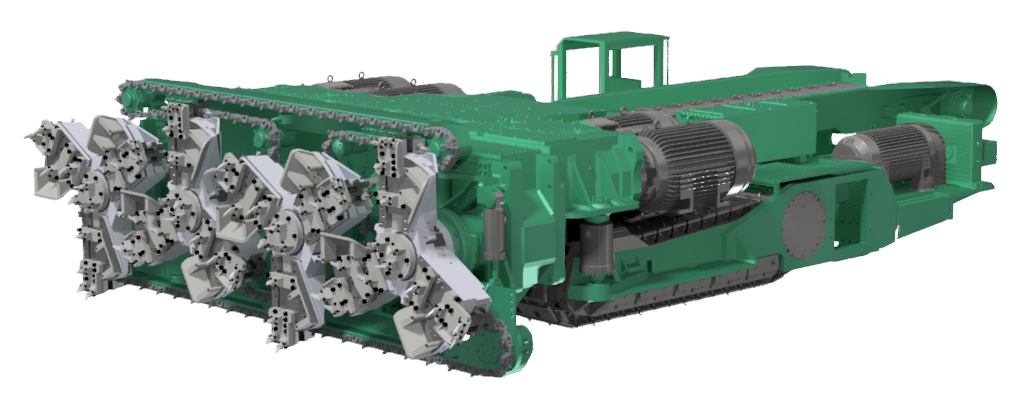

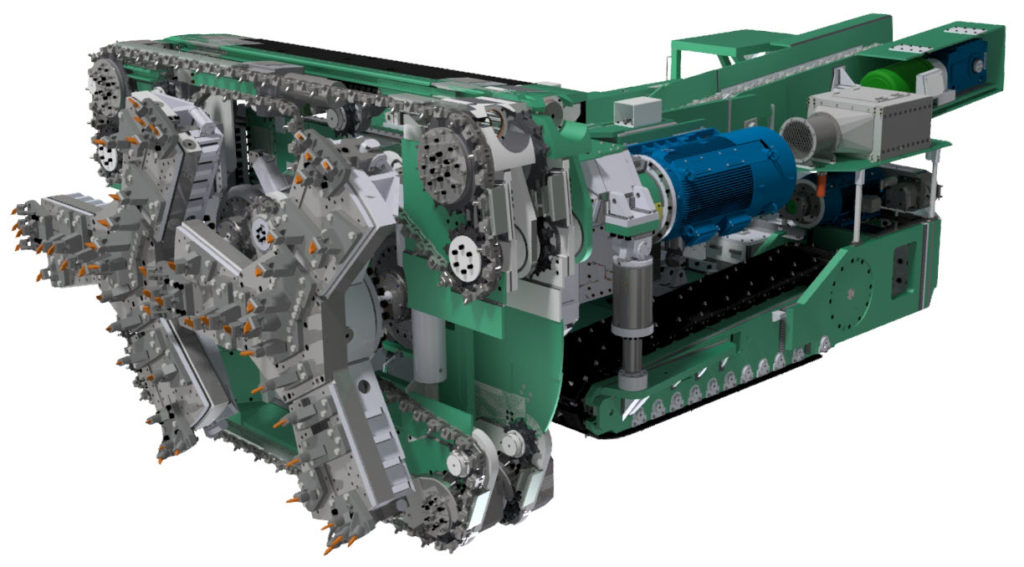

4-rotor borer

Potash, also termed sylvanite, mainly consists of intermixed halite (rock salt) and sylvite (potash) crystals. There are also minor amounts of insolubles (clays) and sometimes carnallite (a magnesium salt). Sylvite (KCl) is the pay dirt, salt is the gangue mineral.

The production rooms being mined were about 75 ft. wide and 5,000 ft. long. That is quite a large span, not likely possible in many other rock types other than salt rock. Overall, the mine would extract about 40-45% of the potash, leaving behind the rest in the form of large pillars to support the overlying rock mass.

2-rotor borer

The mines use continuous miners or borers. In the 80’s they were Marietta miners and now they use borers from Prairie Machine (read more here). When I was there they were starting to transition from two-rotor to four rotor machines. The small machines would carve out ~350 tph, and the large ones could do over ~700 tph.

All borers are directly connected to the massive underground conveyor network that moves the ore from the cutter head to the shaft in a continuous process.

Mining excavates an 8 ft. high room consisting of three layers of interest. A 4.3 ft. layer of high grade ore, a 1.7 ft. layer of low grade ore, and a 2.5 ft. layer of moderate grade potash. This adds up to 8.5 ft., so the miners try to take the best 8 feet. The best head grade would be delivered if the borer cut exactly to the top of the high grade 4.3 ft. seam. One didn’t want to overcut into overlying salt or undercut and leave high grade behind in the roof. I’ll have more on how grade control was done in Part 2.

The air temperature underground is about 25C, so it’s quite a pleasant short sleeve climate. Around the cutting face, the electric motors, and cutter head, temps can reach into the high 30 degree range. Hot but better than freezing. The mine was dry with very low humidity. Hence metal didn’t rust. However, bring the metal to surface and it would rust in no time.

Potash is termed a plastic rock, in that it will deform slowly under stress. Hard rock will build up stresses and erupt violently in a “rock burst”. Potash will go with the flow and deform. Pillars will compress vertically and expand horizontally. Room heights can decrease over time as much as 6 inches over several weeks in higher stress areas.

Potash is termed a plastic rock, in that it will deform slowly under stress. Hard rock will build up stresses and erupt violently in a “rock burst”. Potash will go with the flow and deform. Pillars will compress vertically and expand horizontally. Room heights can decrease over time as much as 6 inches over several weeks in higher stress areas.

Interestingly when the borer shut down and all was quiet, one could walk to the freshly cut face. You could hear the potash walls gently crackling like rice krispies, as the potash expanded into the opening. After all, a few moments earlier the potash was being laterally confined under a vertical stress of 3,000 psi. That confinement is suddenly gone.

Roof closure was always an issue. In panels that were almost mined out, all the ground stress was being carried by the unmined ground. When advancing into this ground, roof closure could be so rapid that once a borer finished a 4 to 6 week room, the miner operator would need to cut a few inches off the roof to get back to the front of the room. It took a couple of days to get the borer out, rather than during a regular shift.

In very high stress areas you could see the floor heaving up as pillars were compressing laterally. That’s when you really knew that mining panel was done and operations should relocate to a new area.

I recall inspecting some of the very old workings from 20 years past. The rooms looked like new except the roof had compressed down to 5 ft. in height. We’d have to drive leaning sideways out of the jeep because the steering wheel was literally scraping the roof.

Flooded Russian Potash Mine

For a year or so, I also worked as a production foreman. It was an interesting role. How does a young mining engineer four years out of school tell guys working underground for 20 years what they need to do?

For a year or so, I also worked as a production foreman. It was an interesting role. How does a young mining engineer four years out of school tell guys working underground for 20 years what they need to do?

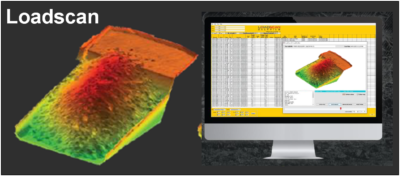

Loadscan has been around for a few years, but I only became aware of it recently. It is a technology that allows the rapid assessment of the load being carried in truck. It does not rely on the use of load cells or weigh scales to measure the payload.

Loadscan has been around for a few years, but I only became aware of it recently. It is a technology that allows the rapid assessment of the load being carried in truck. It does not rely on the use of load cells or weigh scales to measure the payload. What is interesting about this technology is that it is simple to install in an operation. It does not require retrofitting of a truck.

What is interesting about this technology is that it is simple to install in an operation. It does not require retrofitting of a truck. SedimentIQ is a new smartphone vehicle tracking platform that is trying to establish itself. Their proposed technology makes use of a phone’s built-in GPS, Bluetooth, and accelerometer to track vehicle operation. The phone’s sensor can measure vibrations produced by an operating truck or loader.

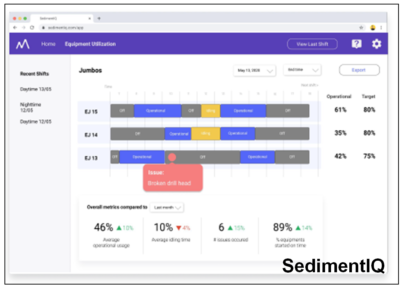

SedimentIQ is a new smartphone vehicle tracking platform that is trying to establish itself. Their proposed technology makes use of a phone’s built-in GPS, Bluetooth, and accelerometer to track vehicle operation. The phone’s sensor can measure vibrations produced by an operating truck or loader. The SedimentIQ software will aggregate the cycle time and delay information and upload it in real time to a cloud based database. A web-based dashboard allows anyone with access to view the real time production data graphically or export it to Excel.

The SedimentIQ software will aggregate the cycle time and delay information and upload it in real time to a cloud based database. A web-based dashboard allows anyone with access to view the real time production data graphically or export it to Excel.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction. There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project.

There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project. An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit.

An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit. Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time?

Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time? As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

This pessimism training started early in my career while working as a geotechnical engineer. Geotechnical engineers were always looking at failure modes and the potential causes of failure when assessing factors of safety.

This pessimism training started early in my career while working as a geotechnical engineer. Geotechnical engineers were always looking at failure modes and the potential causes of failure when assessing factors of safety. When undertaking a due diligence, particularly for a major company or financier, we are not hired to tell them how great the project is. We are hired to look for fatal flaws, identify poorly based design assumptions or errors and omissions in the technical work. We are mainly looking for negatives or red flags.

When undertaking a due diligence, particularly for a major company or financier, we are not hired to tell them how great the project is. We are hired to look for fatal flaws, identify poorly based design assumptions or errors and omissions in the technical work. We are mainly looking for negatives or red flags. It has been my experience that digging in a data room or speaking with the engineering consultants can reveal issues not identifiable in a 43-101 report. Possibly some of these issues were mentioned or glossed over in the report, but you won’t understand the full extent of the issues until digging deeper.

It has been my experience that digging in a data room or speaking with the engineering consultants can reveal issues not identifiable in a 43-101 report. Possibly some of these issues were mentioned or glossed over in the report, but you won’t understand the full extent of the issues until digging deeper. My hesitance in investing in some companies unfortunately can be penalizing. I may end up sitting on the sidelines while watching the rising stock price. Junior mining investors tend to be a positive bunch, when combined with good promotion can result in investors piling into a stock.

My hesitance in investing in some companies unfortunately can be penalizing. I may end up sitting on the sidelines while watching the rising stock price. Junior mining investors tend to be a positive bunch, when combined with good promotion can result in investors piling into a stock. Most times the issue is something we couldn’t fully address given the level of study. We might have been forced to make best guess assumptions to move forward. The review engineers will have their opinions about what assumptions they would have used. Typically the common comment is that our assumption is too optimistic and their assumption would have been more conservative or realistic (in their view).

Most times the issue is something we couldn’t fully address given the level of study. We might have been forced to make best guess assumptions to move forward. The review engineers will have their opinions about what assumptions they would have used. Typically the common comment is that our assumption is too optimistic and their assumption would have been more conservative or realistic (in their view).

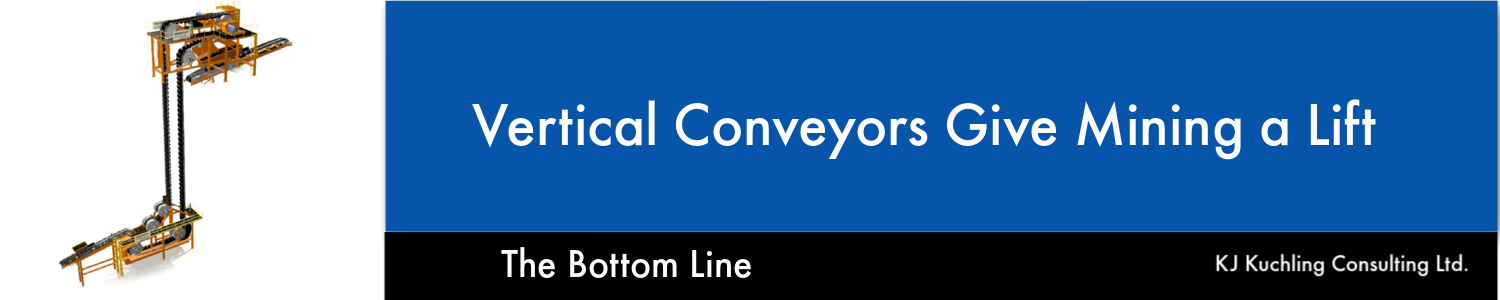

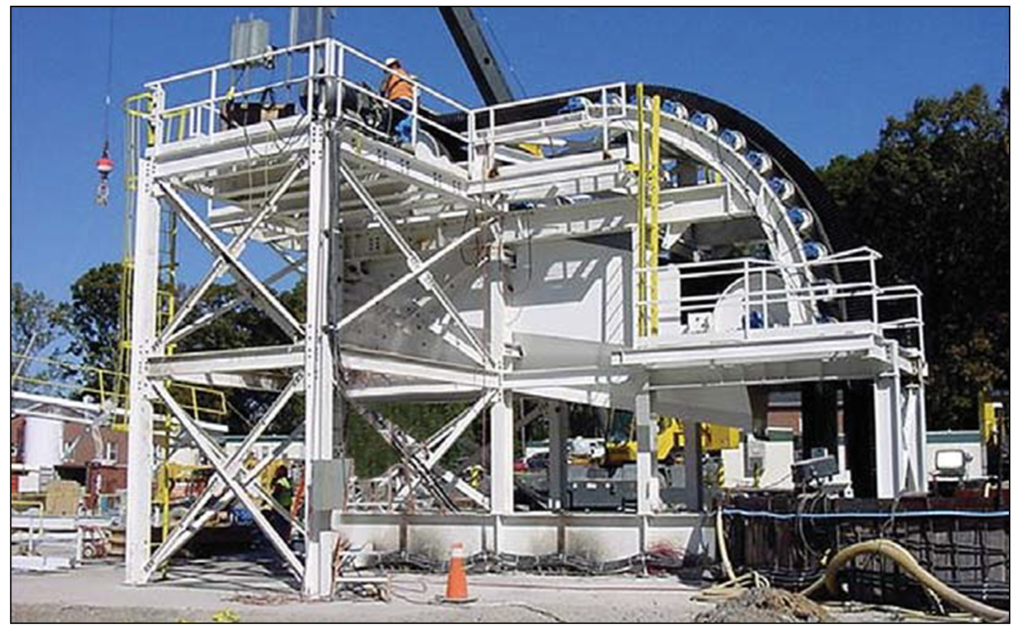

The background information on vertical conveying was provided to me by FKC-Lake Shore, a construction contractor that installs these systems. FKC itself does not fabricate the conveyor hardware. A link to their website is

The background information on vertical conveying was provided to me by FKC-Lake Shore, a construction contractor that installs these systems. FKC itself does not fabricate the conveyor hardware. A link to their website is  The FLEXOWELL®-conveyor system is capable of running both horizontally and vertically, or any angle in between. These conveyors consist of FLEXOWELL®-conveyor belts comprised of 3 components: (i) Cross-rigid belt with steel cord reinforcement; (ii) Corrugated rubber sidewalls; (iii) transverse cleats to prevent material from sliding backwards. They can handle lump sizes varying from powdery material up to 400 mm (16 inch). Material can be raised over 500 metres with reported capacities up to 6,000 tph.

The FLEXOWELL®-conveyor system is capable of running both horizontally and vertically, or any angle in between. These conveyors consist of FLEXOWELL®-conveyor belts comprised of 3 components: (i) Cross-rigid belt with steel cord reinforcement; (ii) Corrugated rubber sidewalls; (iii) transverse cleats to prevent material from sliding backwards. They can handle lump sizes varying from powdery material up to 400 mm (16 inch). Material can be raised over 500 metres with reported capacities up to 6,000 tph. Vendors have evaluated the use of vertical conveying against the use of a conventional vertical shaft hoisting. They report the economic benefits for vertical conveying will be in both capital and operating costs.

Vendors have evaluated the use of vertical conveying against the use of a conventional vertical shaft hoisting. They report the economic benefits for vertical conveying will be in both capital and operating costs. The vendors indicate the conveying system should be able to achieve heights of 700 metres. This may facilitate the use of internal shafts (winzes) to hoist ore from even greater depths in an expanding underground mine. It may be worth a look at your mine.

The vendors indicate the conveying system should be able to achieve heights of 700 metres. This may facilitate the use of internal shafts (winzes) to hoist ore from even greater depths in an expanding underground mine. It may be worth a look at your mine.

Based on my own career, mining has definitely provided me with a chance to travel the world. It will also help anyone overcome their fear of travel. One will also learn that both international and domestic travel can be as equally rewarding. There is nothing wrong with learning more about your own country.

Based on my own career, mining has definitely provided me with a chance to travel the world. It will also help anyone overcome their fear of travel. One will also learn that both international and domestic travel can be as equally rewarding. There is nothing wrong with learning more about your own country.

Business travel has always been one of the best parts of my mining career. I can remember the details about a lot of the travel that I did. Unfortunately the project details themselves will blur with those of other projects.

Business travel has always been one of the best parts of my mining career. I can remember the details about a lot of the travel that I did. Unfortunately the project details themselves will blur with those of other projects.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy. With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation.

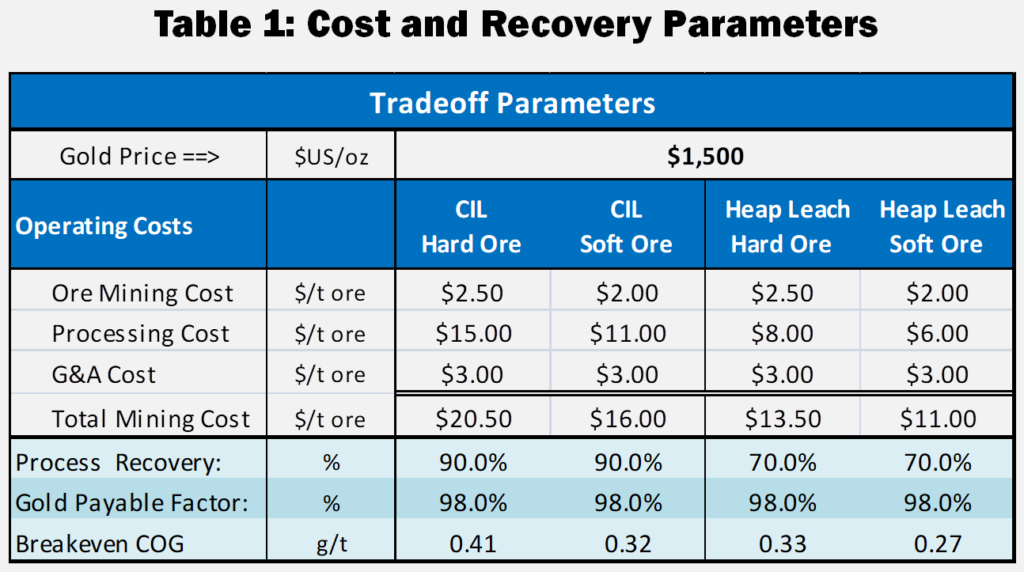

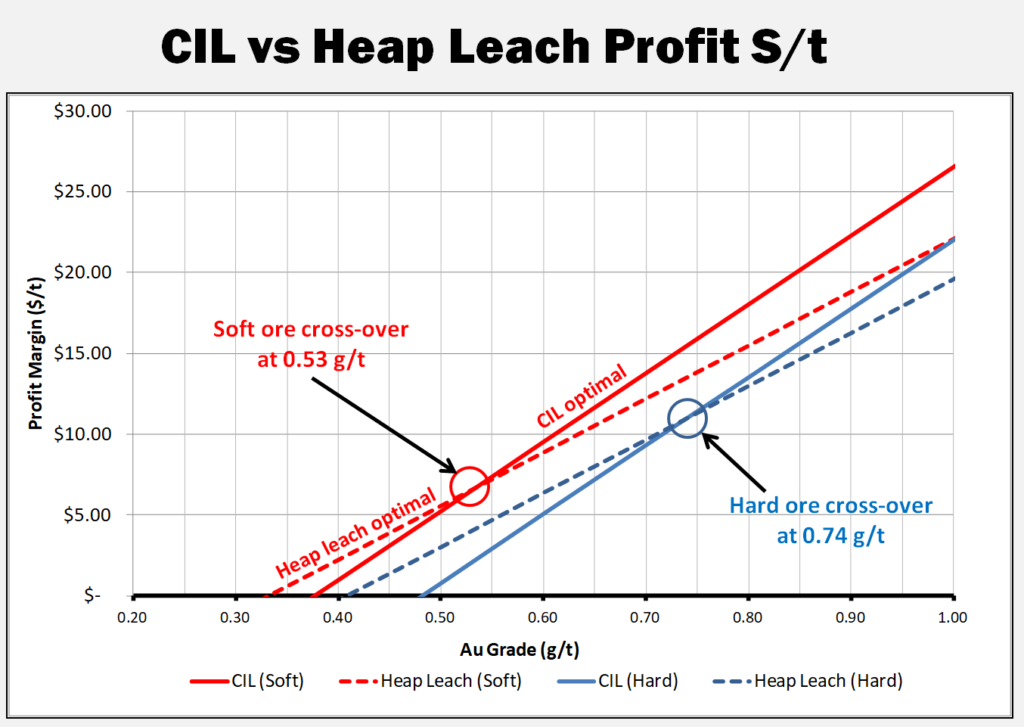

With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation. I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz.

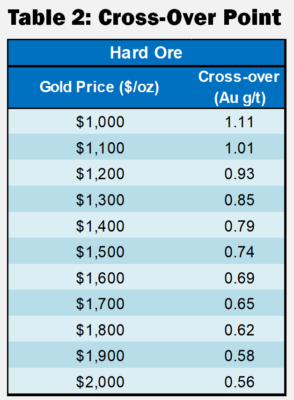

I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz. These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

Normally I don’t write about mining stock markets, preferring instead to focus on technical matters. However I have seen some recent discussions on Twitter about stock price trends. For every stock there are a wide range of price expectations. Ultimately some of the expectations and realizations can be linked back to the Lassonde Curve.

Normally I don’t write about mining stock markets, preferring instead to focus on technical matters. However I have seen some recent discussions on Twitter about stock price trends. For every stock there are a wide range of price expectations. Ultimately some of the expectations and realizations can be linked back to the Lassonde Curve.

Stage 5 is the start-up and commercial production period, possibly nerve-racking for some investors. This is where the rubber hits the road. The stock price can fall if milled grades, operating costs, or production rates are not as expected.

Stage 5 is the start-up and commercial production period, possibly nerve-racking for some investors. This is where the rubber hits the road. The stock price can fall if milled grades, operating costs, or production rates are not as expected. Some corporate presentations will highlight the Lassonde Curve, particularly when they are rising in Stage 1. You are less likely to see the curve presented when they are rolling along in Stages 2 or 3.

Some corporate presentations will highlight the Lassonde Curve, particularly when they are rising in Stage 1. You are less likely to see the curve presented when they are rolling along in Stages 2 or 3.

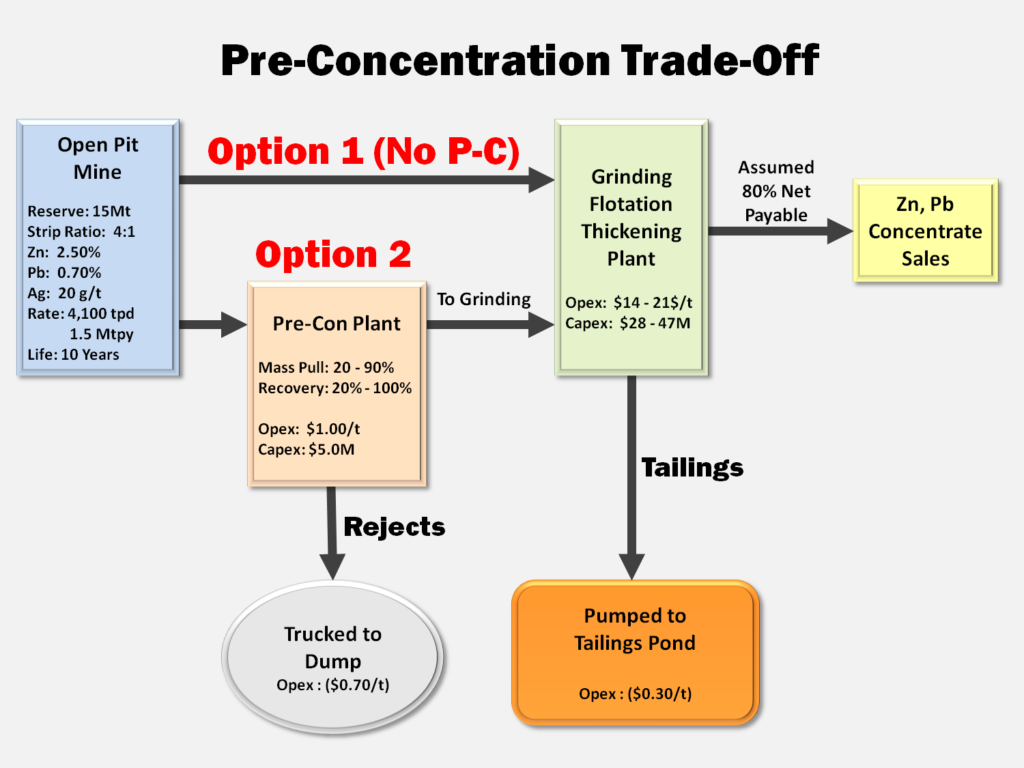

Concentrate handling systems may not differ much between model options since roughly the same amount of final concentrate is (hopefully) generated.

Concentrate handling systems may not differ much between model options since roughly the same amount of final concentrate is (hopefully) generated.

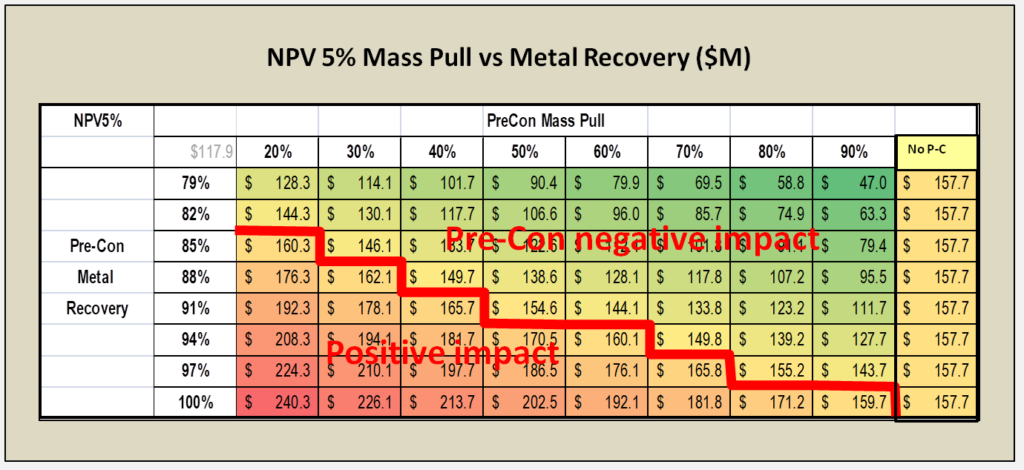

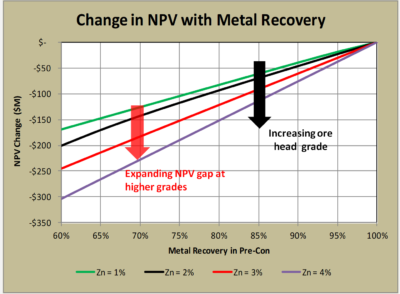

4. The head grade of the deposit also determines how economically risky pre-concentration might be. In higher grade ore bodies, the negative impact of any metal loss in pre-concentration may be offset by accepting higher cost for grinding (see chart on the right).

4. The head grade of the deposit also determines how economically risky pre-concentration might be. In higher grade ore bodies, the negative impact of any metal loss in pre-concentration may be offset by accepting higher cost for grinding (see chart on the right).

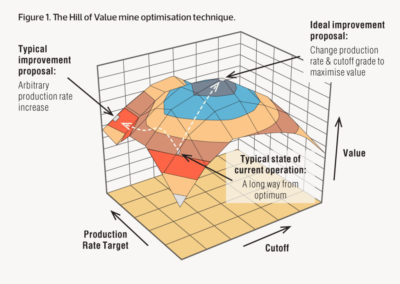

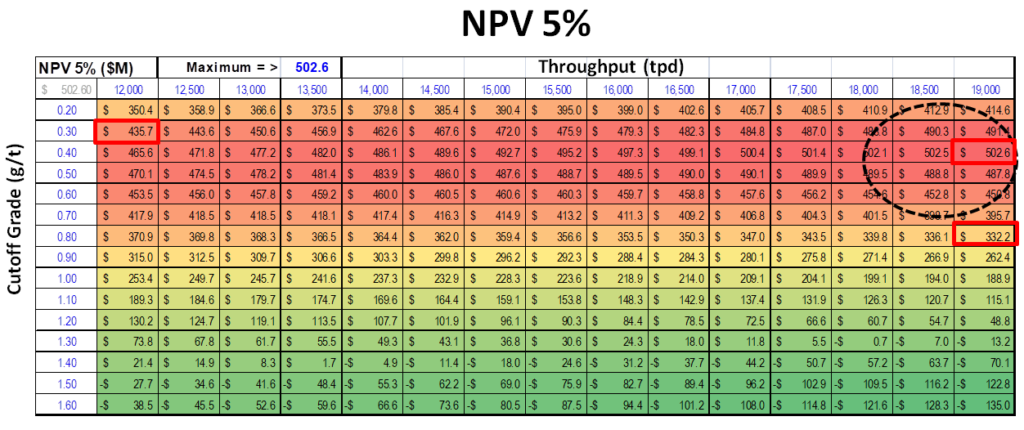

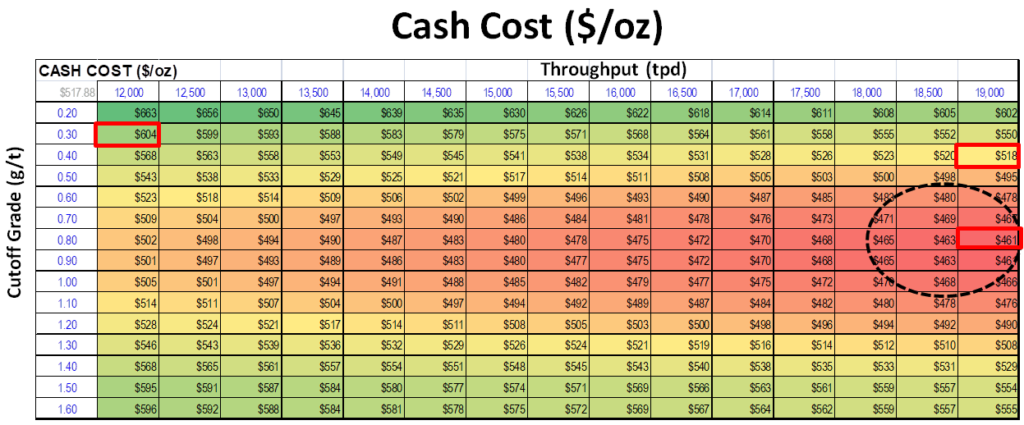

I had a grade tonnage curve, including the tonnes of ore and waste, for a designed pit. This data is shown graphically on the right. Essentially the mineable reserve is 62 Mt @ 0.94 g/t Pd with a strip ratio of 0.6 at a breakeven cutoff grade of 0.35 g/t. It’s a large tonnage, low strip ratio, and low grade deposit. The total pit tonnage is 100 Mt of combined ore and waste.

I had a grade tonnage curve, including the tonnes of ore and waste, for a designed pit. This data is shown graphically on the right. Essentially the mineable reserve is 62 Mt @ 0.94 g/t Pd with a strip ratio of 0.6 at a breakeven cutoff grade of 0.35 g/t. It’s a large tonnage, low strip ratio, and low grade deposit. The total pit tonnage is 100 Mt of combined ore and waste.

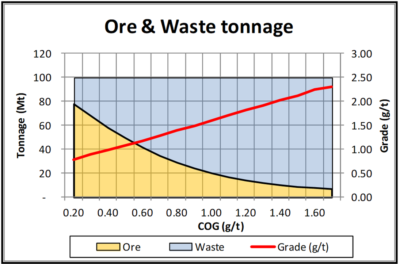

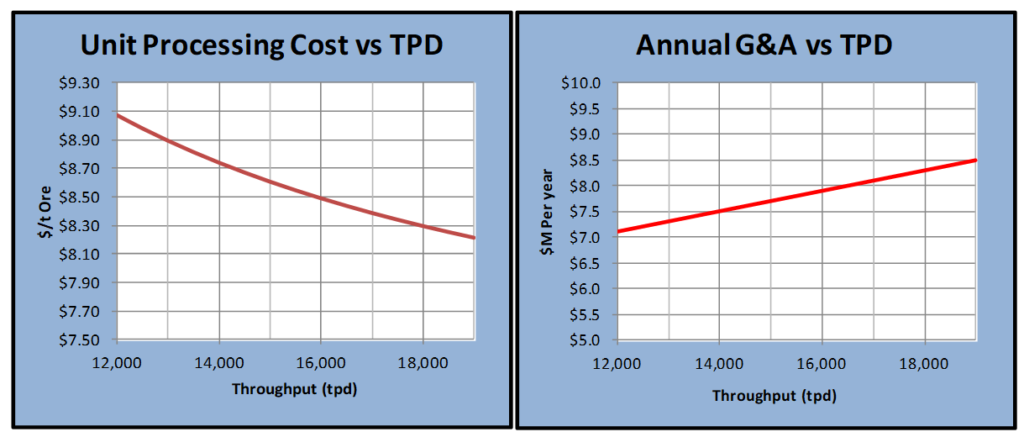

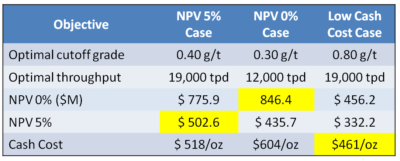

The Hill of Value is an interesting optimization concept to apply to a project. In the example I have provided, the optimal project varies depending on what the financial objective is. I don’t know if this would be the case with all projects, however I suspect so.

The Hill of Value is an interesting optimization concept to apply to a project. In the example I have provided, the optimal project varies depending on what the financial objective is. I don’t know if this would be the case with all projects, however I suspect so.