The article is Part 2 of discussion on my experiences working in the oilsands at the Syncrude Mine in northern Alberta. Part 1 can be read at this link https://kuchling.com/a-rookie-in-the-oilsands-part-1/

In Part 1, I described the great Engineer-in-Training rotational program that Syncrude had in place for new engineering graduates. Initially I had rotated through the Overburden Geotechnical and Industrial Engineering departments. I was then fortunate enough to go though the Mine Geotechnical department and Short Range Planning. Here are some experiences from those assignments.

Will the Draglines Be Safe

Syncrude had four large walking draglines, each with a 80 cubic metre bucket and 110 metre operating radius. These were very big machines; you could sit one in the end zone of a football field and the bucket would be digging (or dumping) in the other end zone. Two draglines were on the East side of the mine and two were on the West, mining the oilsand in 25 m wide strips.

Syncrude had four large walking draglines, each with a 80 cubic metre bucket and 110 metre operating radius. These were very big machines; you could sit one in the end zone of a football field and the bucket would be digging (or dumping) in the other end zone. Two draglines were on the East side of the mine and two were on the West, mining the oilsand in 25 m wide strips.

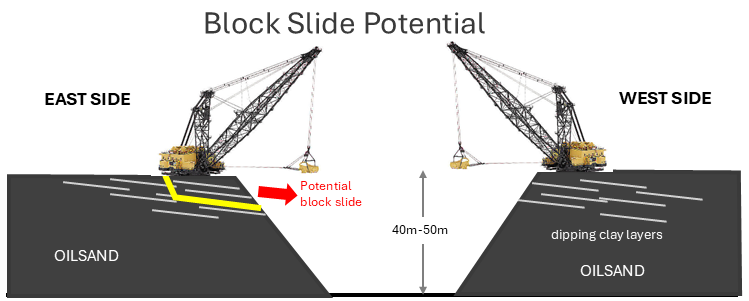

Mining oilsand while from the top of a 50 metre high and 45 degree highwall had never been done before. The geotechnical conditions were new. They were also dramatically different on the East and West sides of the mine, even though mining in the same orebody.

The East side was far more a greater geotechnical concern than the West side. I happened to be the West side mine geotechnical engineer (lucky for me I guess).

The oil sands are sedimentary deposits, and consist of inter-layered sands, silts and clays. At the Syncrude mine, the clay layers were regionally dipping towards the west at 5 to 10 degrees (as shown in the sketch below). Hence they were dipping into the wall on the West side and dipping out of the wall on the East side. The orebody also contained ancient creek scour channels, now infilled with clays and sands.

On the flanks of these scour zones, the thin clay layers could dip up to 25 degrees out of the wall. This was a problem. In university we learned rock slope failures generally require 30-35 deg dipping joint structures for sliding to occur; but here in the clays, sliding (block slides) could occur along 15 to 25 deg dips.

There were numerous instances of East mine block slides, where large portions of the upper slope would fail as large blocks, 50 metres long and up to 30 metres back from the crest. The fear was that if a dragline happened to be sitting on one of these failing blocks, the entire machine would slide along into the pit. Many block slides did occur over the years, but only a few came close to jeopardizing a machine. The geotechnical monitoring programs in place were successful (described later).

There were numerous instances of East mine block slides, where large portions of the upper slope would fail as large blocks, 50 metres long and up to 30 metres back from the crest. The fear was that if a dragline happened to be sitting on one of these failing blocks, the entire machine would slide along into the pit. Many block slides did occur over the years, but only a few came close to jeopardizing a machine. The geotechnical monitoring programs in place were successful (described later).

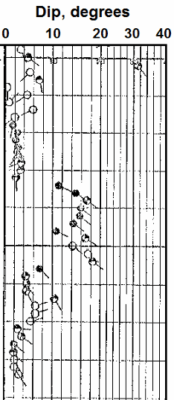

The insitu clay structures were identified using oil and gas borehole logging technology, with tadpole dipmeter plots (see image) used to analyse the bedding (the tail on the tadpole shows the dip direction). The vertical axis is depth from surface or elevation. The geotech engineers would use this information, combined with structural mapping of previously mined faces, to forecast potentially unstable areas.

The insitu clay structures were identified using oil and gas borehole logging technology, with tadpole dipmeter plots (see image) used to analyse the bedding (the tail on the tadpole shows the dip direction). The vertical axis is depth from surface or elevation. The geotech engineers would use this information, combined with structural mapping of previously mined faces, to forecast potentially unstable areas.

In these problem areas, the geotech teams would install slope indicators that were monitored while the dragline was mining through the area. Dedicated 24 hour field engineers were assigned to each of the East side draglines and mining operations were closely monitored at all times.

It was not uncommon for the Syncrude geotechnical engineer to get a 2 am phone call at home saying movement has been detected and they walked the dragline back from the face and then get asked “What should we do now?”.

In the places that the engineers knew were going to be very risk, they could implement mitigation measures. How would you deal with the steeper scour zones? They had three main options.

-

mine through the area with intense geotechnical monitoring in place, using slope indicators, survey prisms, and visual ground inspections.

-

sub-excavate the zone; using the dragline to dig out the area and then backfill with the same material to destroy the clay bedding. Then they could safely mine through the area, although the days used to sub-excavate would remove the dragline from oilsand production.

-

another option was to blast the area ahead of time, to destroy the clay bedding and allow pore pressure dissipation.

All three options were available at the discretion of the geotechnical engineering team. However they all cost money and/or loss in mining production, but safety was always the priority.

The four draglines are now mothballed and thankfully none were ever harmed. All oilsand mining operations are now based on truck-shovel systems.

Basal Slope Failures

On the West side of the mine, the bedding was mainly into the highwall, so block slides were not a major concern. In my brief time there, we never had a block slide on the West side although we did continually review dipmeter plots and face mapping results. One still couldn’t be too careful or get lazy.

The main geotechnical issue on the West side were basal slope failures, termed this due to sliding along weak clays and muds at the base of the highwall. This photo shows a typical basal failure. Basal failures also occured on the East side.

The main geotechnical issue on the West side were basal slope failures, termed this due to sliding along weak clays and muds at the base of the highwall. This photo shows a typical basal failure. Basal failures also occured on the East side.

Generally, these slope failures did not jeopardize the dragline since they occurred on freshly cut highwalls away from the machine. Eventually the dragline would be required to operate next to existing basal failures when mining the next panel (as shown in the photo).

The dragline would sit 15-25 metres from the wall, the closer is better to maximize reach into the pit.

The main concern with basal failures was that the toe of the failed slope would move beyond the reach of the dragline and could not be mined. As well, sometimes the dragline would need to cast waste layers back into the mined out pit while avoiding the burial of the oilsand toe. If the waste couldn’t be cast back inpit due to toe failure, it would be placed on the operating bench and trucked away later (at a cost).

The Alberta government focused on maximizing oilsand resource recovery. If the dragline could not reach the ore due to a failure, we would need to send mobile equipment down to get it. If we couldn’t do this due to access issues, we needed to prepare an Ore Loss Report that was tracked and submitted to the government agency (ERCB). We hated to submit those reports, taking it as a personal disappointment that we couldn’t get to that ore.

In the basal failure photo, one can see a vertical scarp next to the dragline. The oilsands were a “locked sand” in that the sand grains were tightly compacted or interlocked from the compressive weight of over a kilometre of glacial ice thickness in the past. The vertical scarps would stand indefinitely, sometime spalling off in slabs. The oilsand itself was a very strong geotechnical unit (friction angles in excess of 50 degrees).

Conclusion

Once our engineer-in-training rotation program was complete, we were to be assigned to a more permanent position. For me, that was going to be as an East side geotechnical engineer – ugh!. It’s at that time I decided to look for greener pastures. Three years was long enough from 1980 to 1983; given the amount of learning and responsibility I had undertaken. Other colleagues left the same time, while many other friends stayed in Ft McMurray for their entire careers.

Once our engineer-in-training rotation program was complete, we were to be assigned to a more permanent position. For me, that was going to be as an East side geotechnical engineer – ugh!. It’s at that time I decided to look for greener pastures. Three years was long enough from 1980 to 1983; given the amount of learning and responsibility I had undertaken. Other colleagues left the same time, while many other friends stayed in Ft McMurray for their entire careers.

In Part 1 of this two part blog post I would like to share some stories from the early days of my career working in Fort McMurray.

In Part 1 of this two part blog post I would like to share some stories from the early days of my career working in Fort McMurray. At the time Syncrude had an excellent engineer-in-training program for new graduates. Every six months they would rotate engineers into different technical areas.

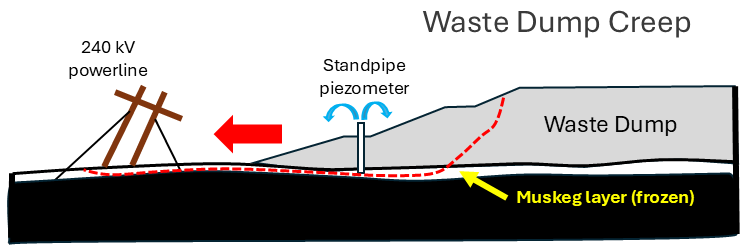

At the time Syncrude had an excellent engineer-in-training program for new graduates. Every six months they would rotate engineers into different technical areas. Next we sampled that depth carefully, revealing that frozen muskeg layers were present. When we installed standpipe piezometers in these holes, we saw water flowing out of the top of the pipes. This means the foundation pore pressure is high, way too high.

Next we sampled that depth carefully, revealing that frozen muskeg layers were present. When we installed standpipe piezometers in these holes, we saw water flowing out of the top of the pipes. This means the foundation pore pressure is high, way too high. For example, one project I had was to monitor the performance of different brands and styles of conveyor idlers. We would track about 2,000 individual idlers; when they were installed on the conveyors; when they were removed, why they were removed (bearing failure, cover failure, something else).

For example, one project I had was to monitor the performance of different brands and styles of conveyor idlers. We would track about 2,000 individual idlers; when they were installed on the conveyors; when they were removed, why they were removed (bearing failure, cover failure, something else).

The mining industry is implementing more and more technology in the mining cycle.

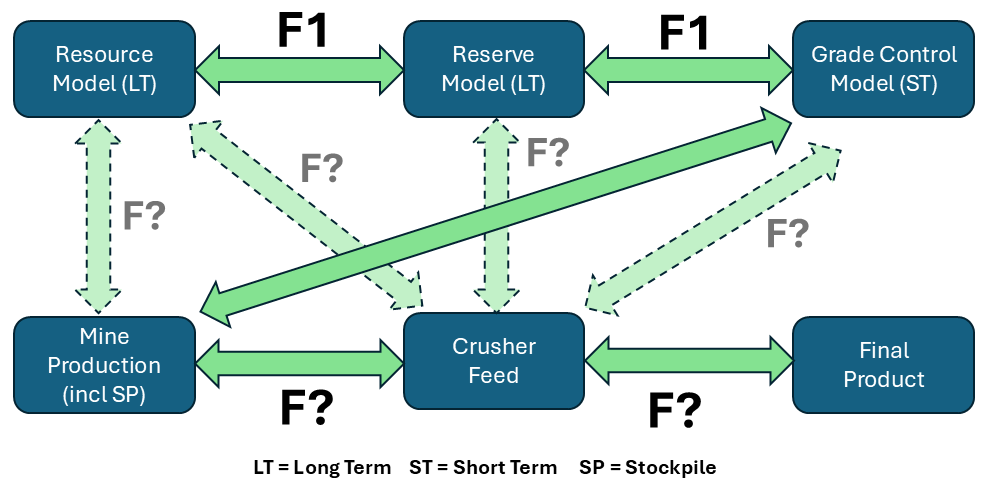

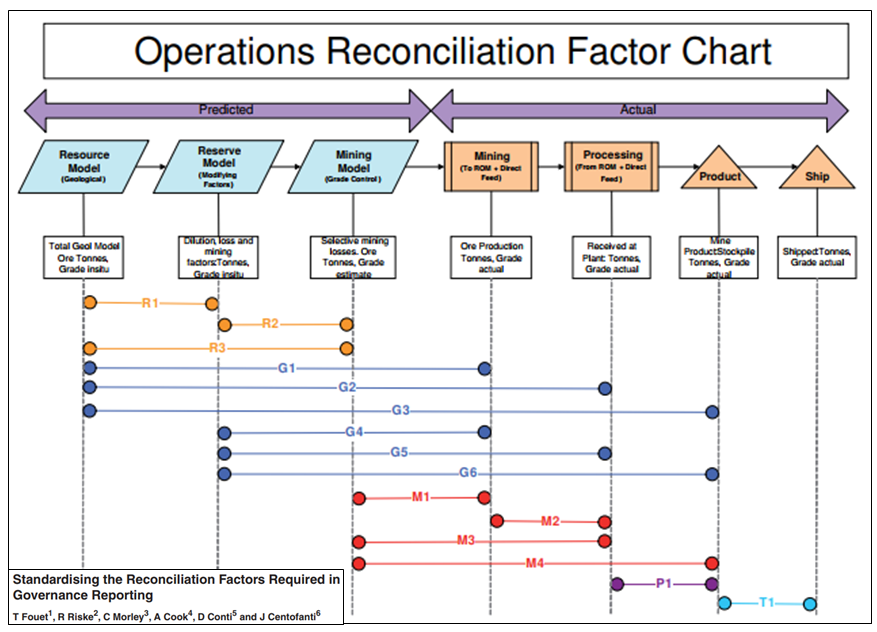

The mining industry is implementing more and more technology in the mining cycle. Mine reconciliation requires information such as initial predictions from exploration data and geological models, actual measurement: data from mining sources, such as blast holes, stockpile samples, or mill feed. As well it will need data on the final product being shipped off site. Do the metal quantities balance out throughout the mining operation?

Mine reconciliation requires information such as initial predictions from exploration data and geological models, actual measurement: data from mining sources, such as blast holes, stockpile samples, or mill feed. As well it will need data on the final product being shipped off site. Do the metal quantities balance out throughout the mining operation?

Each mine site may be unique with respect to; ore sources; terminology; ore types; mining methods; stockpiling philosophy; processing methods; technology availability; and personnel capability. So often the easiest approach for mine reconciliation is based on the Excel spreadsheet. (Reconciliation is generally not an easy undertaking).

Each mine site may be unique with respect to; ore sources; terminology; ore types; mining methods; stockpiling philosophy; processing methods; technology availability; and personnel capability. So often the easiest approach for mine reconciliation is based on the Excel spreadsheet. (Reconciliation is generally not an easy undertaking).

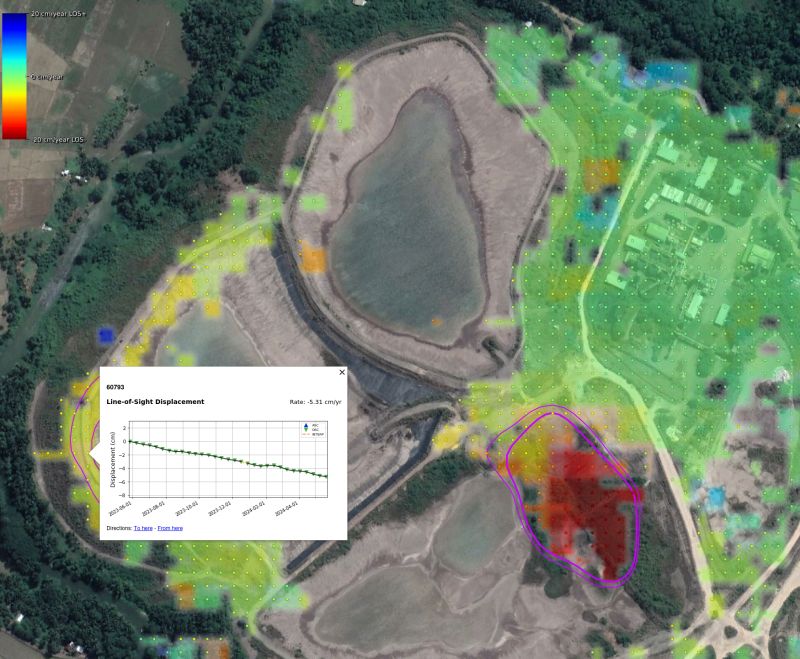

An example of a satellite being used is the Sentinel-1, launched in mid-2015 by the European Space Agency. This satellite information is open-source data. It will have a 6 to 12 day revisit cycle in many locations.

An example of a satellite being used is the Sentinel-1, launched in mid-2015 by the European Space Agency. This satellite information is open-source data. It will have a 6 to 12 day revisit cycle in many locations. On LinkedIn, one can see numerous posts where independent experts are examining historical InSAR data for recent failures to see whether early movement should have been detected. The results seem to be quite positive in that areas that have failed might have been red-flagged prior to failure.

On LinkedIn, one can see numerous posts where independent experts are examining historical InSAR data for recent failures to see whether early movement should have been detected. The results seem to be quite positive in that areas that have failed might have been red-flagged prior to failure. A mining site consists of numerous constructed embankments and slopes of all types and heights. Many of these slopes may be creeping and moving all the time – it’s a living beast.

A mining site consists of numerous constructed embankments and slopes of all types and heights. Many of these slopes may be creeping and moving all the time – it’s a living beast.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times. Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant.

Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant. Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate. These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers. There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work.

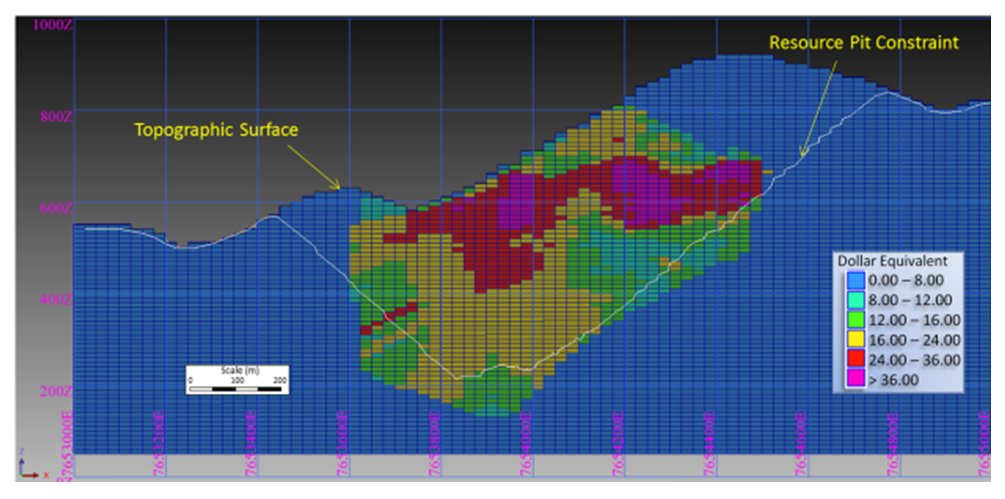

There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work. Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type.

Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type. Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal.

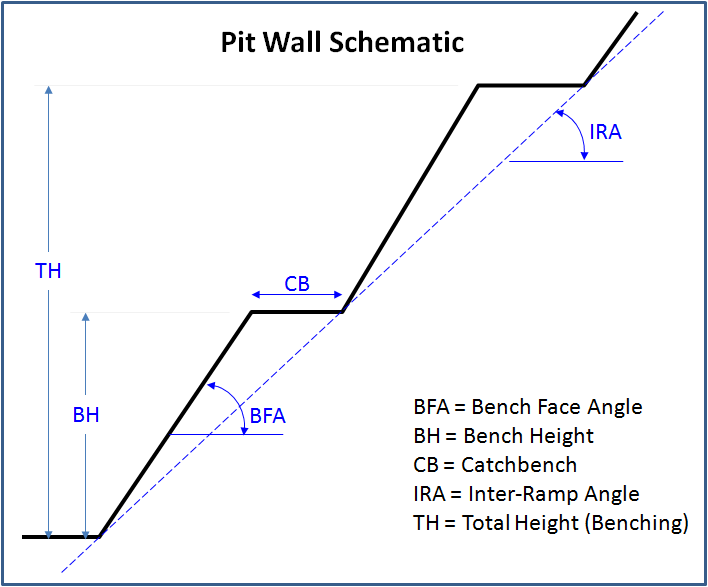

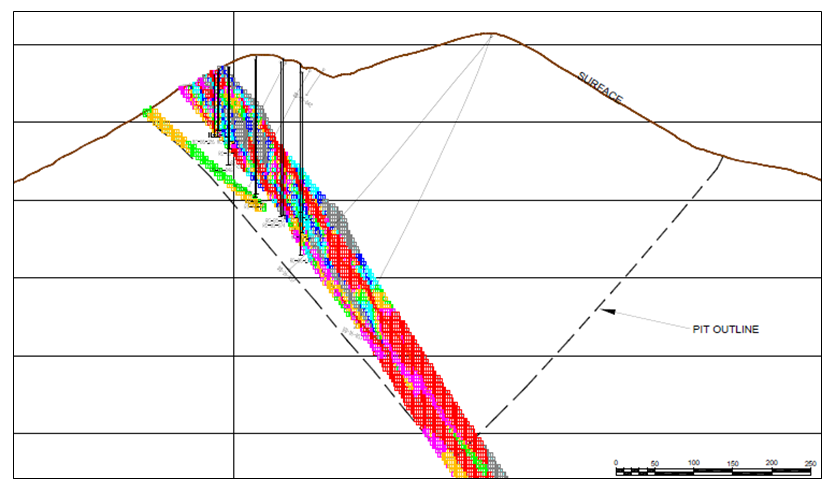

Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal. The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created. This ends Part 1. In Part 2 we will discuss the mining engineer’s next tasks; production scheduling; waste dump design; and equipment selection. The mining engineer QP will sign off and take responsibility for all the mine design work done so far. You can read Part 2 at this link “

This ends Part 1. In Part 2 we will discuss the mining engineer’s next tasks; production scheduling; waste dump design; and equipment selection. The mining engineer QP will sign off and take responsibility for all the mine design work done so far. You can read Part 2 at this link “

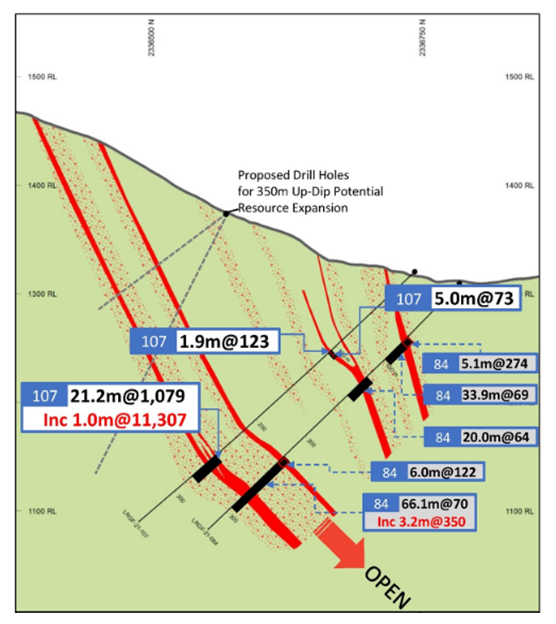

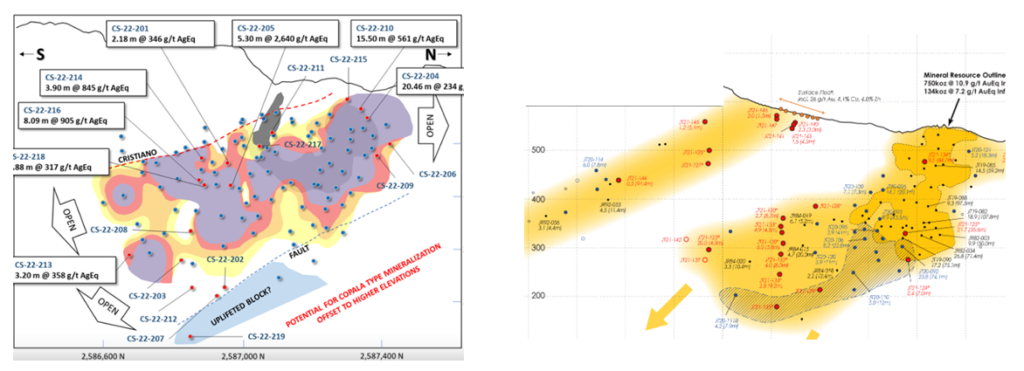

This article is about the benefit of preparing (cutting) more geological cross-sections and the value they bring.

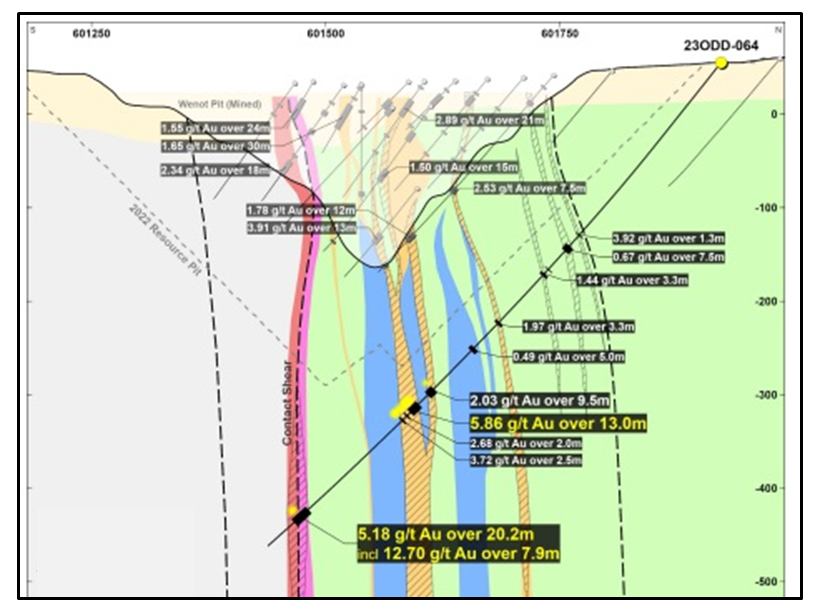

This article is about the benefit of preparing (cutting) more geological cross-sections and the value they bring. Long sections are aligned along the long axis of the deposit. They can be vertically oriented, although sometimes they may be tilted to follow the dip angle of an ore zone.

Long sections are aligned along the long axis of the deposit. They can be vertically oriented, although sometimes they may be tilted to follow the dip angle of an ore zone. When looking at cross-sections, it is always important to look at multiple cross-sections across the orebody. Too often in reports one may be presented with the widest and juiciest ore zone, as if that was typical for the entire orebody. It likely is not typical.

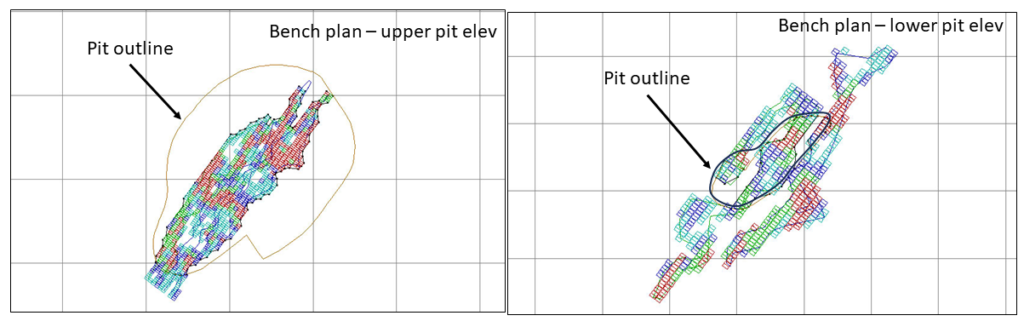

When looking at cross-sections, it is always important to look at multiple cross-sections across the orebody. Too often in reports one may be presented with the widest and juiciest ore zone, as if that was typical for the entire orebody. It likely is not typical. Bench plans (or level plans) are horizontal slices across the ore body at various elevations. In these sections one is looking down on the orebody from above.

Bench plans (or level plans) are horizontal slices across the ore body at various elevations. In these sections one is looking down on the orebody from above. 3D PDF files can be created by some of the geological software packages. They can export specific data of interest; for example topography, ore zone wireframes, underground workings, and block model information. These 3D files allows anyone to rotate an image, zoom in as needed and turn layers off and on.

3D PDF files can be created by some of the geological software packages. They can export specific data of interest; for example topography, ore zone wireframes, underground workings, and block model information. These 3D files allows anyone to rotate an image, zoom in as needed and turn layers off and on. The different types of geological sections all provide useful information. Don’t focus only on cross-sections, and don’t focus only on one typical section. Create more sections at different orientations to help everyone understand better.

The different types of geological sections all provide useful information. Don’t focus only on cross-sections, and don’t focus only on one typical section. Create more sections at different orientations to help everyone understand better.

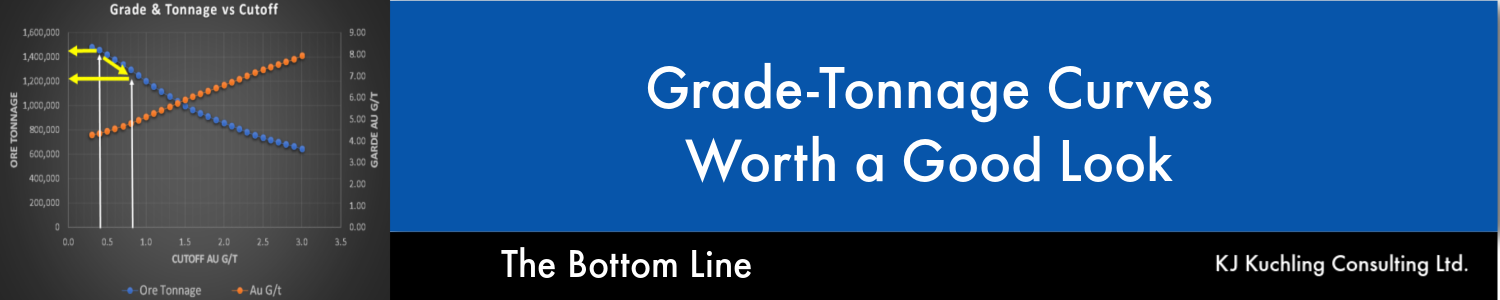

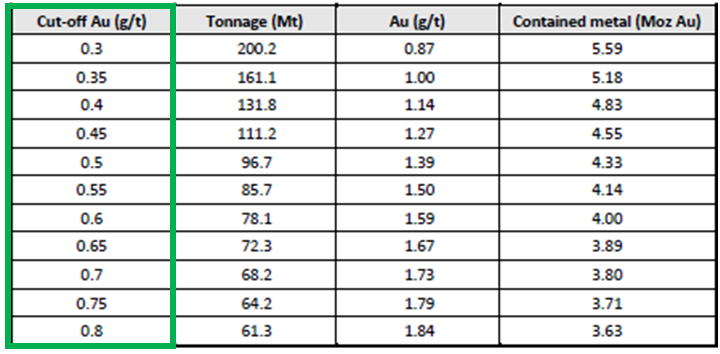

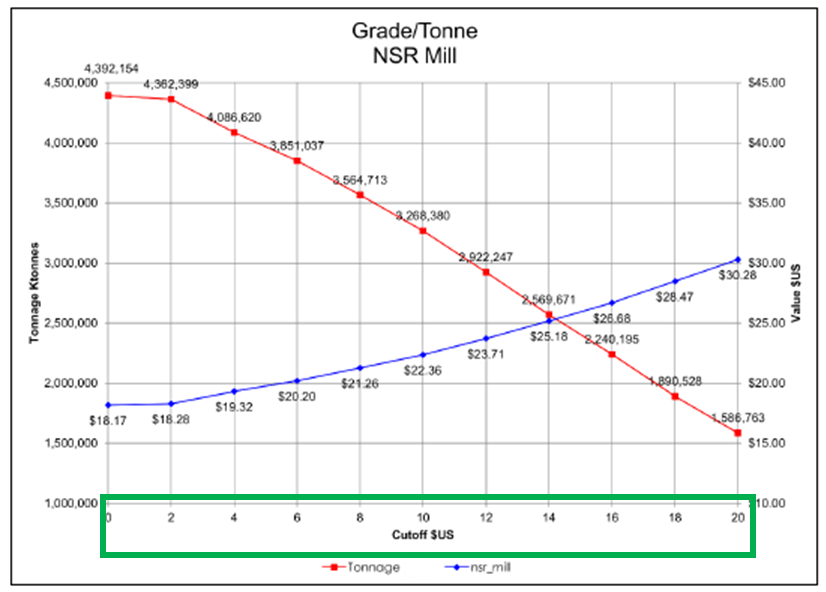

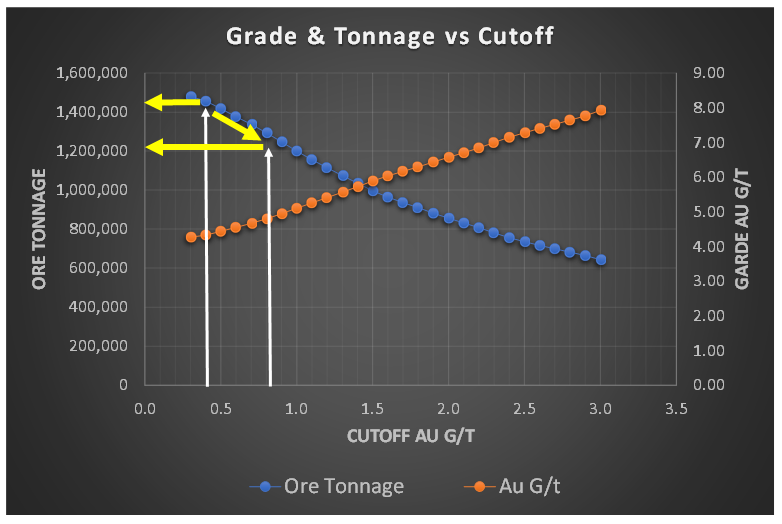

When I am undertaking a due diligence review or working on a study, very early on I like to have a look at the grade-tonnage information. This could be for the entire deposit resource, within a resource constraining shell, or in the pit design.

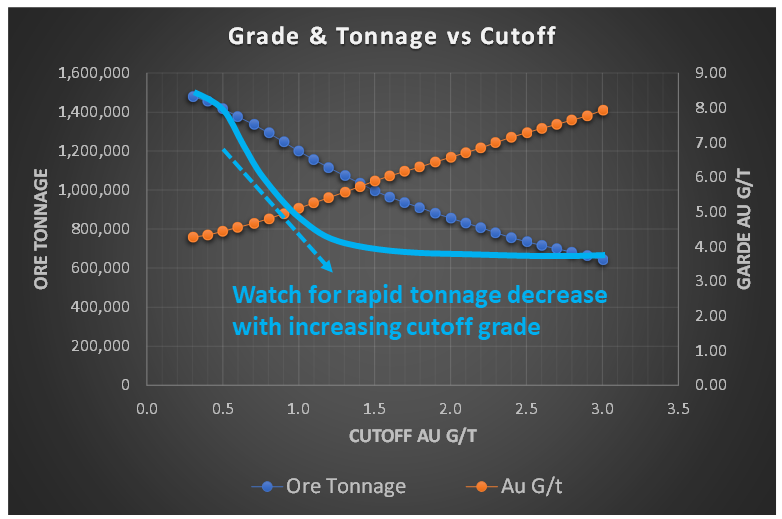

When I am undertaking a due diligence review or working on a study, very early on I like to have a look at the grade-tonnage information. This could be for the entire deposit resource, within a resource constraining shell, or in the pit design. However, if the tonnage curve profile resembled the light blue line in this image, with a concave shape, the ore tonnage is decreasing rapidly with increasing cutoff grade. This is generally not a favorable situation.

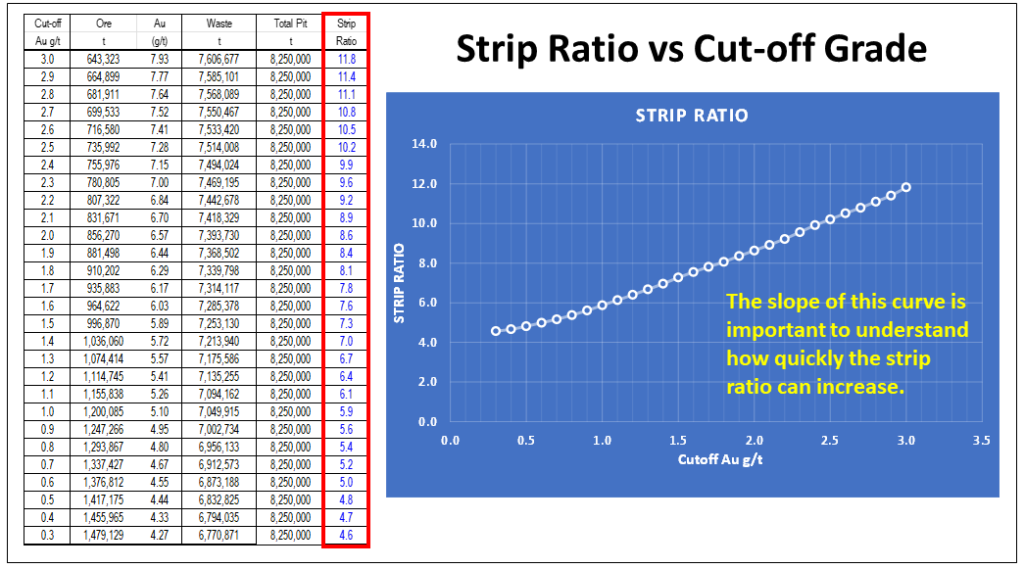

However, if the tonnage curve profile resembled the light blue line in this image, with a concave shape, the ore tonnage is decreasing rapidly with increasing cutoff grade. This is generally not a favorable situation. Regarding mineral resources, one should be required to disclose the waste tonnage and strip ratio when reporting resources inside a constraining shell. The constraining shell and cutoff grade are both based on defined economic factors such as unit mining costs, processing cost, process recoveries, and metal prices. With respect to the mining cost component, the strip ratio is a key aspect of the total mining cost, yet it normally isn’t disclosed.

Regarding mineral resources, one should be required to disclose the waste tonnage and strip ratio when reporting resources inside a constraining shell. The constraining shell and cutoff grade are both based on defined economic factors such as unit mining costs, processing cost, process recoveries, and metal prices. With respect to the mining cost component, the strip ratio is a key aspect of the total mining cost, yet it normally isn’t disclosed. In 43-101 technical reports, the financial Chapter 22 normally presents the project sensitivities expressed in a spider diagram or a table format.

In 43-101 technical reports, the financial Chapter 22 normally presents the project sensitivities expressed in a spider diagram or a table format.

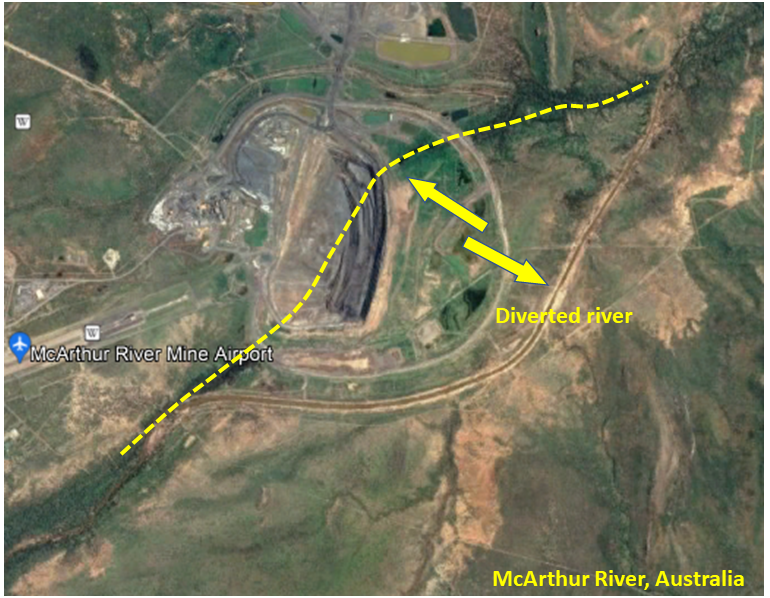

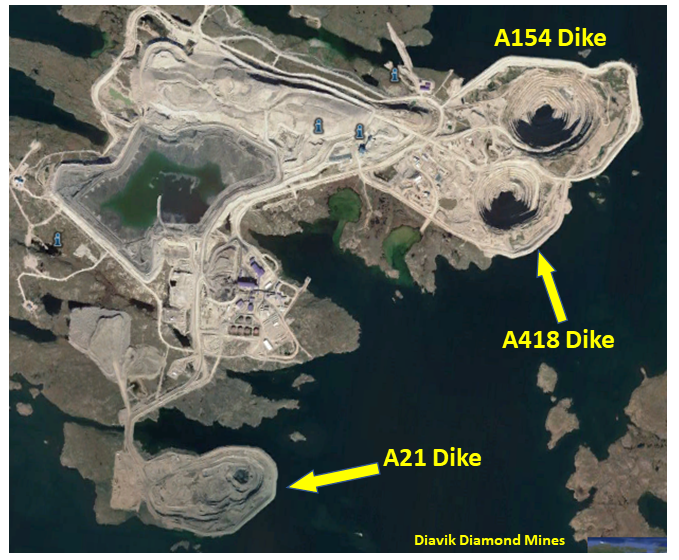

The primary question to be answered is whether one can mine safely and economically without creating significant impacts on the environment.

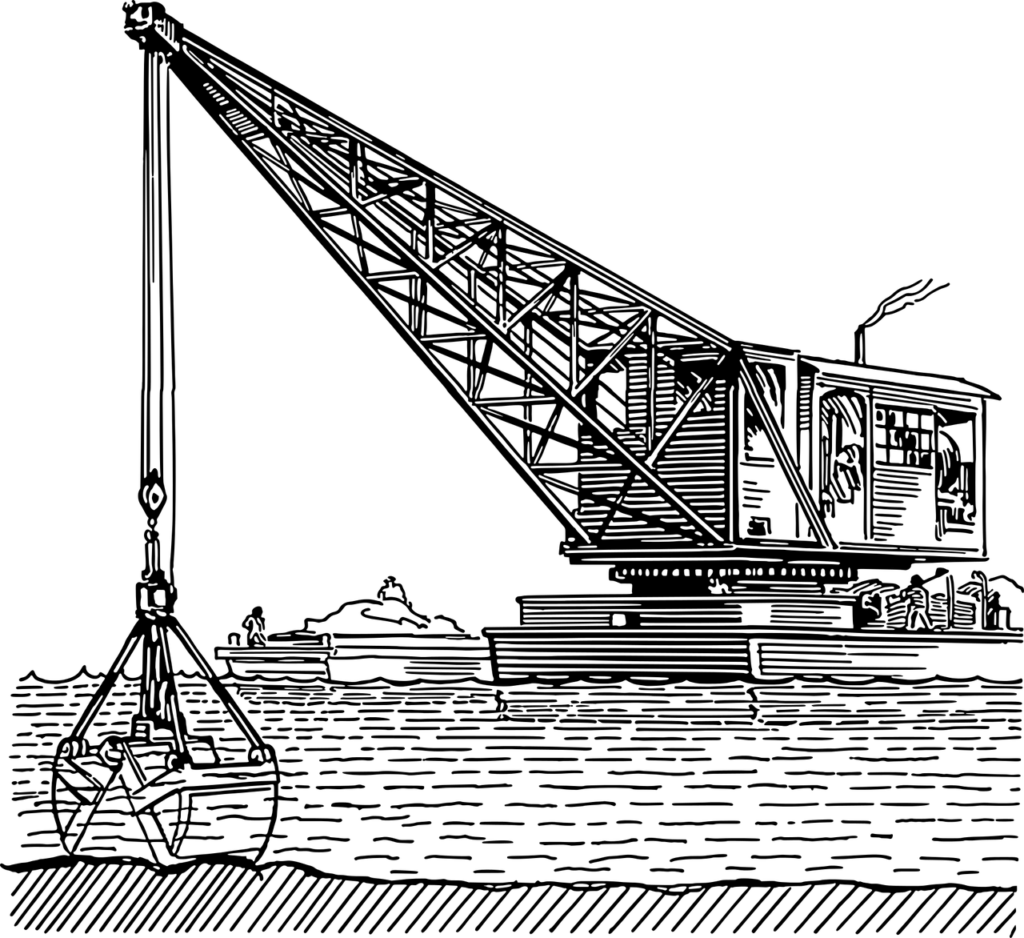

The primary question to be answered is whether one can mine safely and economically without creating significant impacts on the environment. Lake Turbidity: Dike construction will need to be done through the water column. Works such as dredging or dumping rock fill will create sediment plumes that can extend far beyond the dike. Is the area particularly sensitive to such turbidity disturbances, is there water current flow to carry away sediments?

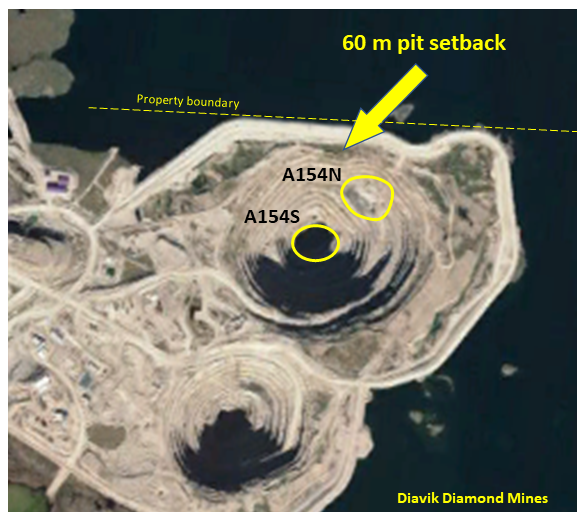

Lake Turbidity: Dike construction will need to be done through the water column. Works such as dredging or dumping rock fill will create sediment plumes that can extend far beyond the dike. Is the area particularly sensitive to such turbidity disturbances, is there water current flow to carry away sediments? Pit wall setback: Given the size and depth of the open pit, how far must the dike be from the pit crest? Its nice to have 200 metre setback distance, but that may push the dike out into deeper water.

Pit wall setback: Given the size and depth of the open pit, how far must the dike be from the pit crest? Its nice to have 200 metre setback distance, but that may push the dike out into deeper water. Once the approximate location of the dike has been identified, the next step is to examine the design of the dike itself. Most of the issues to be considered relate to the geotechnical site conditions.

Once the approximate location of the dike has been identified, the next step is to examine the design of the dike itself. Most of the issues to be considered relate to the geotechnical site conditions. Each mine site is different, and that is what makes mining into water bodies a unique challenge. However many mine operators have done this successfully using various approaches to tackle the challenge.

Each mine site is different, and that is what makes mining into water bodies a unique challenge. However many mine operators have done this successfully using various approaches to tackle the challenge.