This is Part 2 of the blog post discussing junior mining scams and the sanctioning of those responsible. Part 1 can be found at this link “Junior Mining Shams and Scams – Part 1” and can be read first to get some background.

Part 2 provides examples involving professional Qualified Persons (QPs). We may have the feeling that QP’s are never held accountable for their work, but that is not always the case. There are numerous instances of QP’s being hauled off in front of their professional organizations for unprofessionalism. This blog will highlight some of those cases.

The lesson is that QP’s signing off on technical information for clients should be proficient in the nature of their work and need to know the reporting rules very well. Some of these incidents involve error and poor judgment, not outright fraud.

The lesson is that QP’s signing off on technical information for clients should be proficient in the nature of their work and need to know the reporting rules very well. Some of these incidents involve error and poor judgment, not outright fraud.

These examples involve in-house QP’s that work for a company while others involve independent QP’s that have been contracted by the company.

In most of these cases, any sanctions, if applied, were mainly doled out by the professional engineering or geological associations. The legal courts are often not involved.

Examples (Part 2)

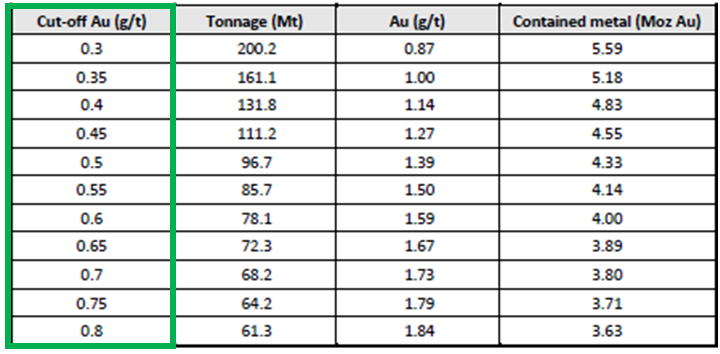

Inaccurate QP Resource Estimate: This example relates to the Barkerville Gold Mines resource estimate complete in 2012. The mineral resource estimate had numerous errors and issues related to assays, capping, cutoff grades, etc. The allegation was the QP had demonstrated incompetence, unprofessional conduct, and negligence. The sanctions on the QP included a $15,000 fine, $20,000 legal costs, re-training, and license suspension.

Link 1:

Link 2:

False QP Statements: Here is an example from 2011. The QP / company Director was charged with multiple allegations, including stating the mine was in commercial production (when it wasn’t), leaving the impression there were mineral resource (which there weren’t any), and generally approving information that was not accurate. Ultimately the allegation was demonstrating incompetence, unprofessional conduct, and negligence. The resulting sanctions included 2 year license suspension, re-training, payment of $80,000 to the professional association.

Link 1:

False QP Statements: This is case were a resource QP failed to comply with the NI43-101, Form 43-101F1, CIM Standards, and CIM Guidelines. The Panel concluded that the Member was guilty of non-compliance with the standards and hence guilty of professional misconduct. Its not clear what specifically was not complied with, but this illustrates that QP’s will be held accountable for their work. The two reports in question were either amended or withdrawn to address the concerns of the regulator in British Columbia, although there had been no intentional non-compliance and no economic impact. The penalty was 2 months suspension (deferred), and the QP had to work under a mentor for 9 months and pay a maximum $10,000 for the mentor’s fees.

Link 1:

False QP Statements: Here is another example of sanctioning a QP in 2018. The person was charged with unprofessional conduct and incompetence. He stated that he was responsible for the preparation of the technical report, had no prior involvement in the project, and was independent of the issuer. This was false. Sanctions included three month license suspension, taking some re-training, require peer review of the report. In 2022, further sanctions consisted of a $75,000 penalty, further sanctioned along with an executive in the company for insider trading issues (see Link 3 below).

Link 1:

Link 2:

Link 3:

False QP Statements: This is an example for 2017 when an independent QP took responsibility for the resource estimation work in section 14 of the report, yet they did not have the experience to take responsibility. They also misrepresented that the Report complied with 2014 CIM standards, yet it didn’t, resulting in an overestimation of the mineral resource in both confidence and magnitude. Other claims include relying on non-QP experts but not stating that, failing to adequately discuss the nature of sample quality control procedures as required. The sanctions included license suspension of 3 months, must work with a technical supervisor, re-training, and $7,500 in legal fees.

Link 1:

False QP Statements: This is another example from 2019, when the QP / Director permitted the disclosure of information to the public in multiple news releases where they should have known that that information was misleading. An example is the disclosure of inferred reserves when there were no reserves and “inferred” is not even a classification of reserves. The sanctions were a license suspension of 4 months, $5,000 legal costs, re-training, and requirement not to act as a QP again.

Link 1:

QP Resource Estimate Error: This occurred in 2012 when a QP and consulting firm delivered a incorrect resource estimate and reportedly withheld negative opinions on the project from the client. The company spent $3 million on a feasibility study during which the resource estimate error was discovered. The “corrected” resource made the project uneconomic, meaning the feasibility study should not have been done. The mining company sought compensation from the consulting firm, ultimately receiving $1.25 million. The Link 3 references is interesting in that it states “As this case demonstrates, it is critically important for professional service firms to be forthcoming about any reservations they may have regarding the work they are being employed to undertake.” Whatever that really means?

Link 1:

Link 2:

Link 3:

Disclaimers

Many QP’s realize the legal responsibility and liability they have. Hence in 43-101 reports QP’s sometimes attempt to mitigate this by putting in broad disclaimers to limited that liability. If the securities commission notices such disclaimers, they will require that they be removed.

For example, sometimes the QP of a chapter may have other geologists or engineers (i.e. experts) assisting them. They may then put in disclaimers saying “They disclaim responsibility for such expert content” for the work done by the others. A QP essentially has to sign off on the work of others in the sections they are responsible for. A recent example is a Generation Mining technical report prepared by G-Mining, that had to be amended from (March 31_2023 to May 31_2024) removing several QP liability limiting disclaimers.

43-101 regulations state that “An issuer must not file a technical report that contains a disclaimer by any qualified person responsible for preparing or supervising the preparation of all or part of the report that

43-101 regulations state that “An issuer must not file a technical report that contains a disclaimer by any qualified person responsible for preparing or supervising the preparation of all or part of the report that

(a) disclaims responsibility for, or limits reliance by another party on, any information in the part of the report the qualified person prepared or supervised the preparation of;

or (b) limits the use or publication of the report in a manner that interferes with the issuer’s obligation to reproduce the report by filing it on SEDAR.“

” These disclaimers are also potentially misleading disclosure because, in certain circumstances, securities legislation provides investors with a statutory right of action against a qualified person for a misrepresentation in disclosure that is based upon the qualified person’s technical report.

That right of action exists despite any disclaimer to the contrary that appears in the technical report. The securities regulatory authorities will generally require the issuer to have its qualified person remove any blanket disclaimers in a technical report that the issuer uses to support its public offering document.“

Conclusion

This ends Part 2 of this blog post. It hopefully highlights the importance of QP’s being knowledgably on the disclosure rules and the technical aspects of what they are hired to do.

This ends Part 2 of this blog post. It hopefully highlights the importance of QP’s being knowledgably on the disclosure rules and the technical aspects of what they are hired to do. The focus of this blog is on the types of activities that raised the red flags in the past. I am less interested in naming the people responsible, although the associated web links do provide more detail on the events.

The focus of this blog is on the types of activities that raised the red flags in the past. I am less interested in naming the people responsible, although the associated web links do provide more detail on the events. This ends Part 1 of this blog post. Part 2 will continue with a few more examples, specifically involving Qualified Persons, and can be found at this link

This ends Part 1 of this blog post. Part 2 will continue with a few more examples, specifically involving Qualified Persons, and can be found at this link

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some.

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some. The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates.

The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates. ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen.

ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen. Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times. Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant.

Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant. Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate. These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers. There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work.

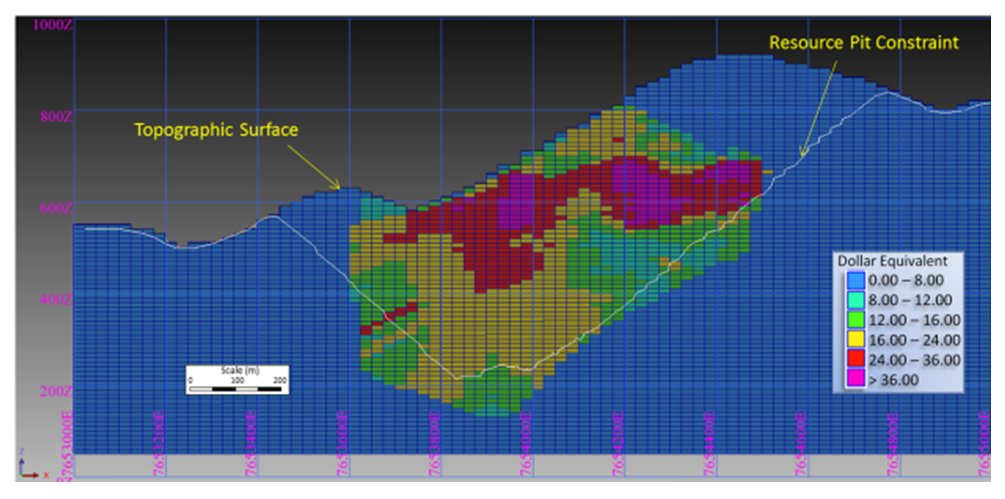

There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work. Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type.

Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type. Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal.

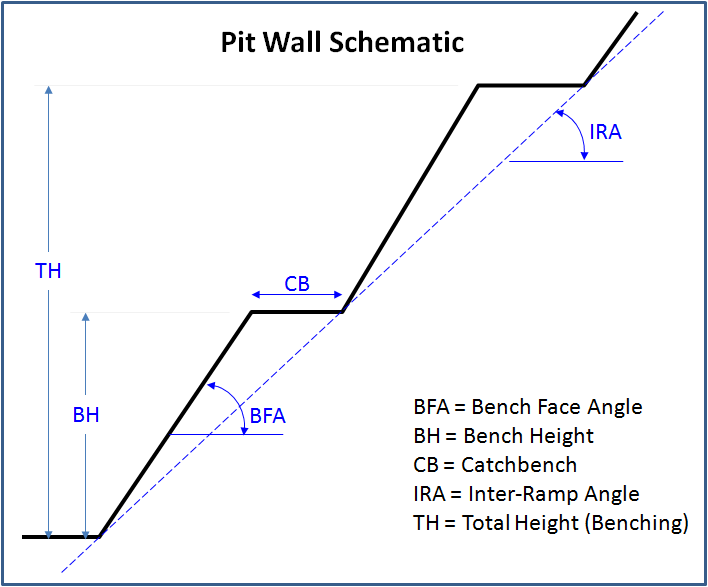

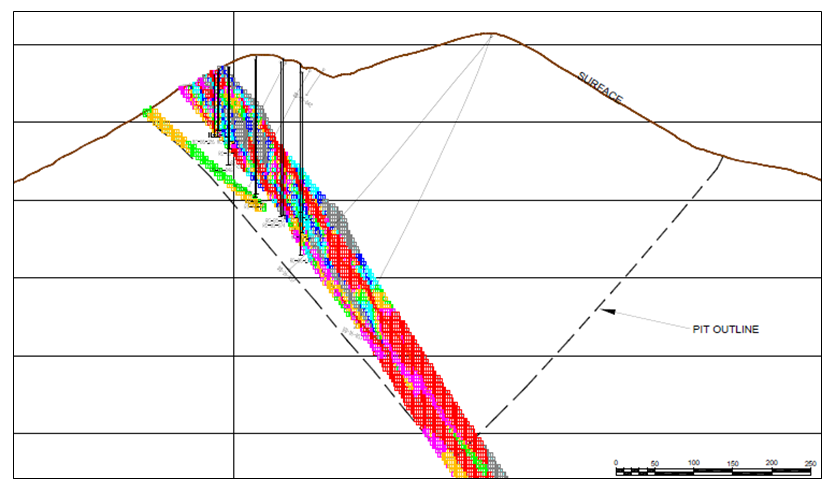

Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal. The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created.

This article is about the benefit of preparing (cutting) more geological cross-sections and the value they bring.

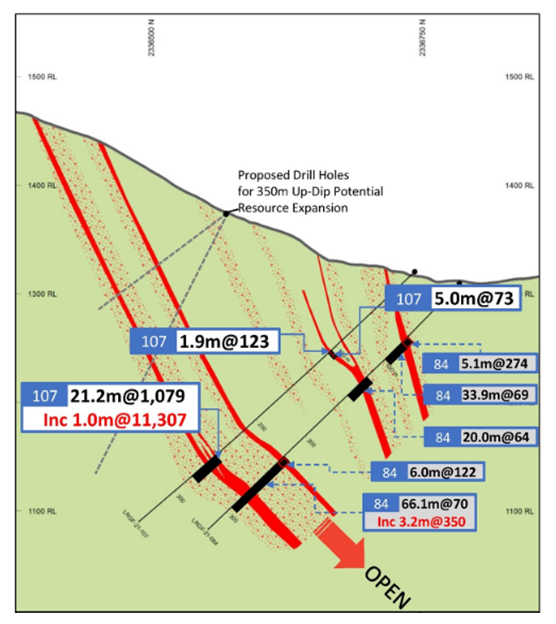

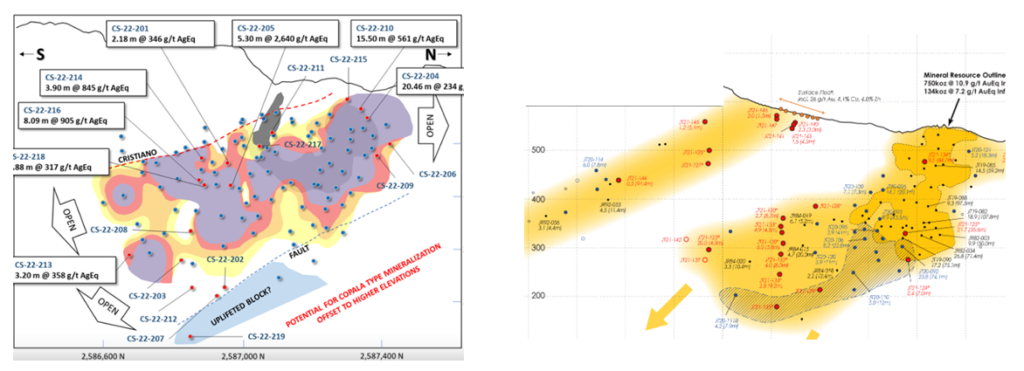

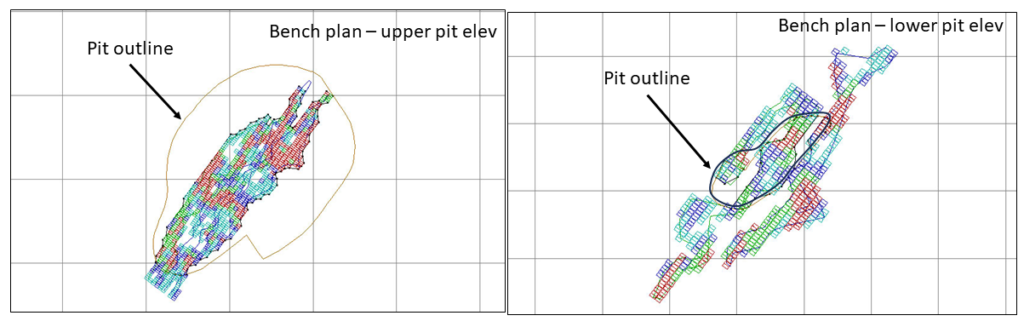

This article is about the benefit of preparing (cutting) more geological cross-sections and the value they bring. Long sections are aligned along the long axis of the deposit. They can be vertically oriented, although sometimes they may be tilted to follow the dip angle of an ore zone.

Long sections are aligned along the long axis of the deposit. They can be vertically oriented, although sometimes they may be tilted to follow the dip angle of an ore zone. When looking at cross-sections, it is always important to look at multiple cross-sections across the orebody. Too often in reports one may be presented with the widest and juiciest ore zone, as if that was typical for the entire orebody. It likely is not typical.

When looking at cross-sections, it is always important to look at multiple cross-sections across the orebody. Too often in reports one may be presented with the widest and juiciest ore zone, as if that was typical for the entire orebody. It likely is not typical. Bench plans (or level plans) are horizontal slices across the ore body at various elevations. In these sections one is looking down on the orebody from above.

Bench plans (or level plans) are horizontal slices across the ore body at various elevations. In these sections one is looking down on the orebody from above. 3D PDF files can be created by some of the geological software packages. They can export specific data of interest; for example topography, ore zone wireframes, underground workings, and block model information. These 3D files allows anyone to rotate an image, zoom in as needed and turn layers off and on.

3D PDF files can be created by some of the geological software packages. They can export specific data of interest; for example topography, ore zone wireframes, underground workings, and block model information. These 3D files allows anyone to rotate an image, zoom in as needed and turn layers off and on. The different types of geological sections all provide useful information. Don’t focus only on cross-sections, and don’t focus only on one typical section. Create more sections at different orientations to help everyone understand better.

The different types of geological sections all provide useful information. Don’t focus only on cross-sections, and don’t focus only on one typical section. Create more sections at different orientations to help everyone understand better.

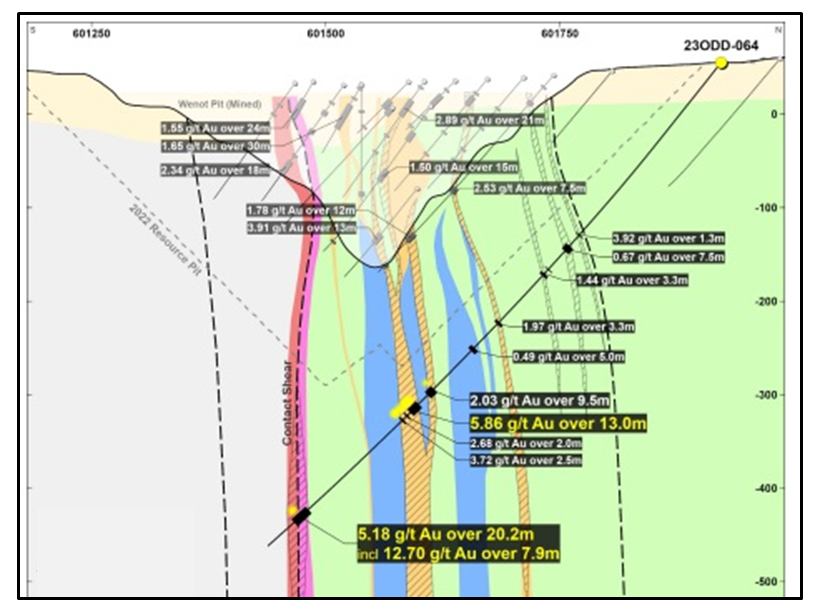

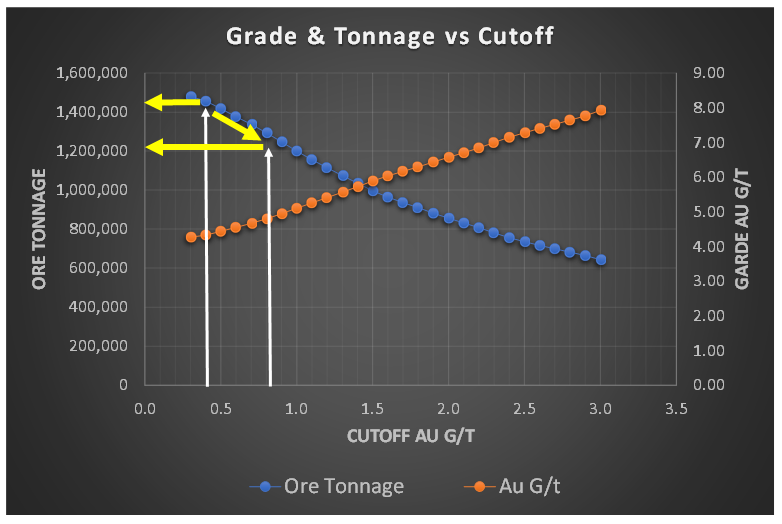

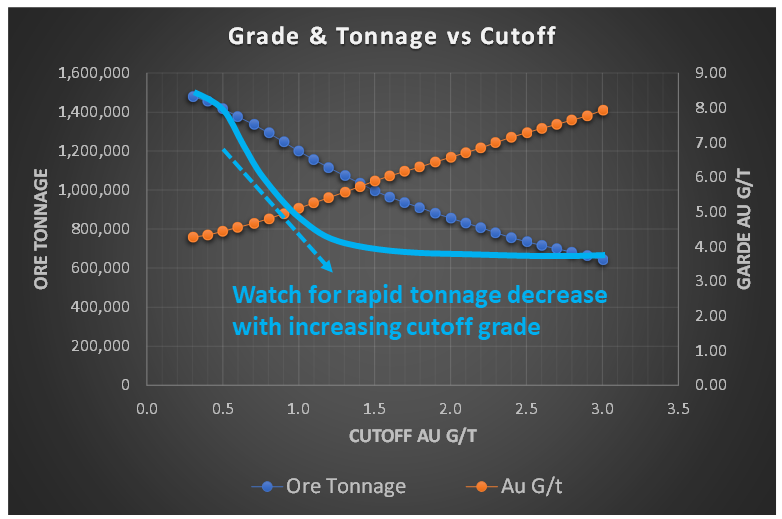

When I am undertaking a due diligence review or working on a study, very early on I like to have a look at the grade-tonnage information. This could be for the entire deposit resource, within a resource constraining shell, or in the pit design.

When I am undertaking a due diligence review or working on a study, very early on I like to have a look at the grade-tonnage information. This could be for the entire deposit resource, within a resource constraining shell, or in the pit design. However, if the tonnage curve profile resembled the light blue line in this image, with a concave shape, the ore tonnage is decreasing rapidly with increasing cutoff grade. This is generally not a favorable situation.

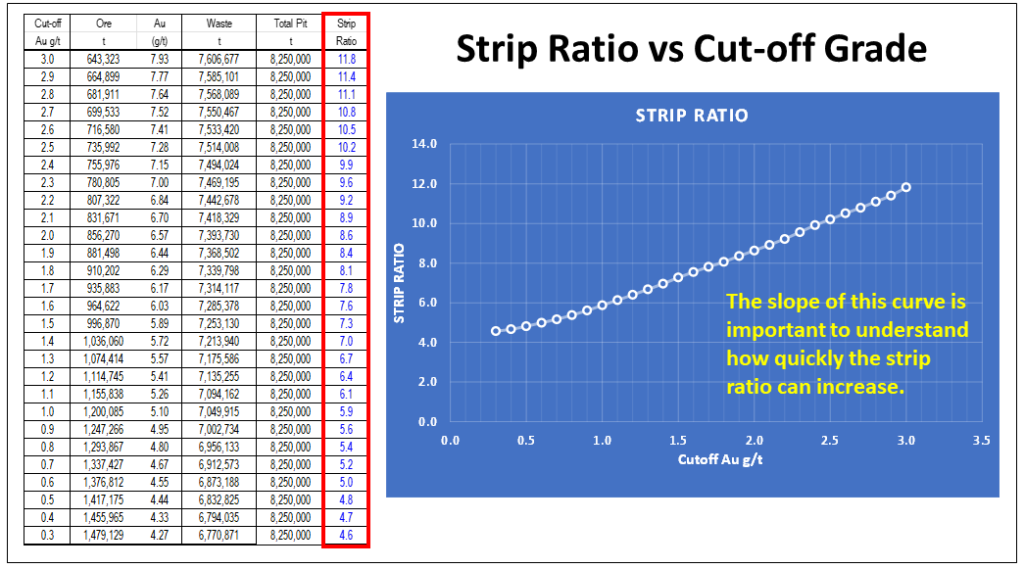

However, if the tonnage curve profile resembled the light blue line in this image, with a concave shape, the ore tonnage is decreasing rapidly with increasing cutoff grade. This is generally not a favorable situation. Regarding mineral resources, one should be required to disclose the waste tonnage and strip ratio when reporting resources inside a constraining shell. The constraining shell and cutoff grade are both based on defined economic factors such as unit mining costs, processing cost, process recoveries, and metal prices. With respect to the mining cost component, the strip ratio is a key aspect of the total mining cost, yet it normally isn’t disclosed.

Regarding mineral resources, one should be required to disclose the waste tonnage and strip ratio when reporting resources inside a constraining shell. The constraining shell and cutoff grade are both based on defined economic factors such as unit mining costs, processing cost, process recoveries, and metal prices. With respect to the mining cost component, the strip ratio is a key aspect of the total mining cost, yet it normally isn’t disclosed. In 43-101 technical reports, the financial Chapter 22 normally presents the project sensitivities expressed in a spider diagram or a table format.

In 43-101 technical reports, the financial Chapter 22 normally presents the project sensitivities expressed in a spider diagram or a table format.

When disclosing polymetallic drill results, many companies will convert the multiple metal grades into a single equivalent grade. I am not a big proponent of that approach.

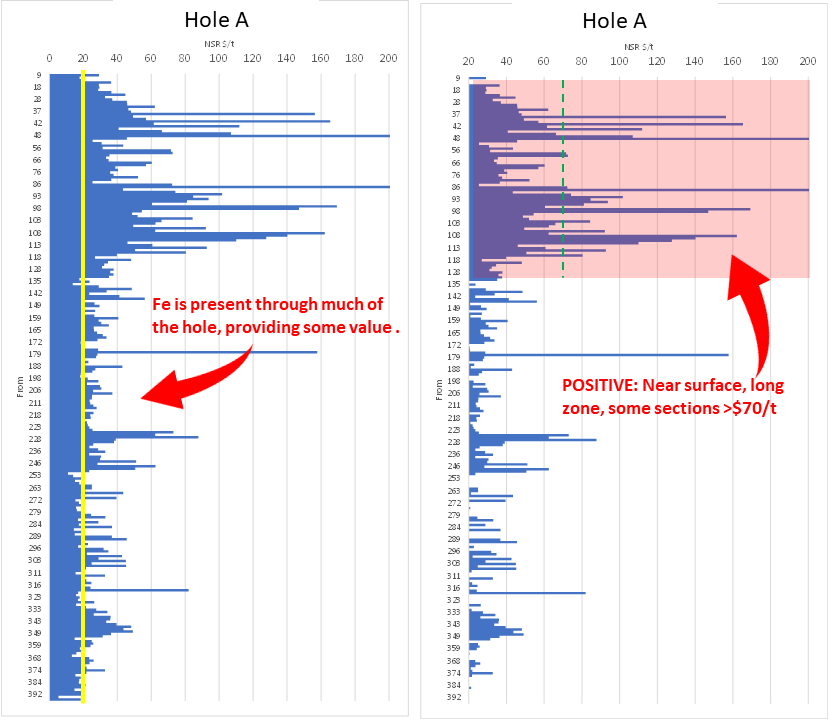

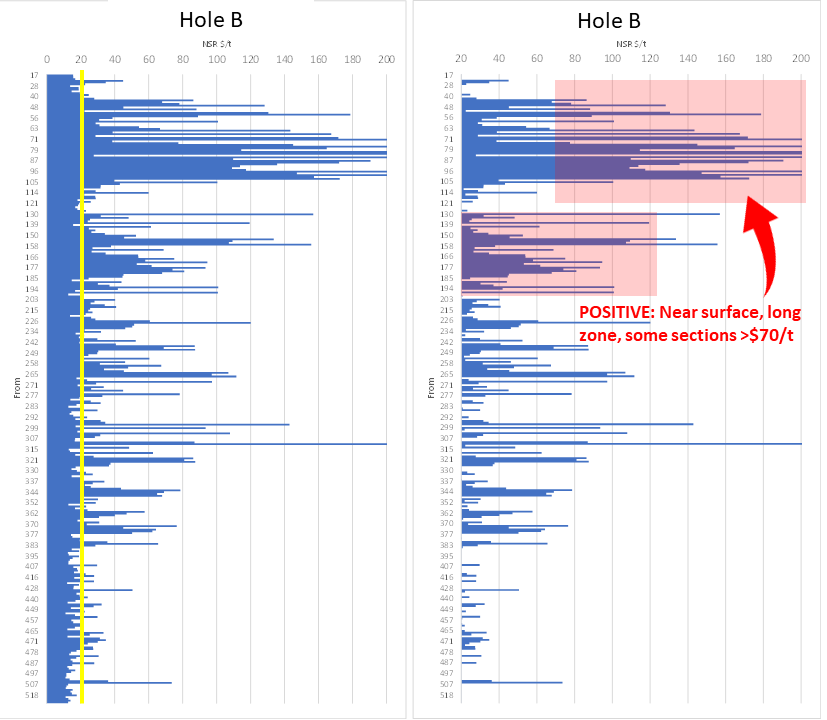

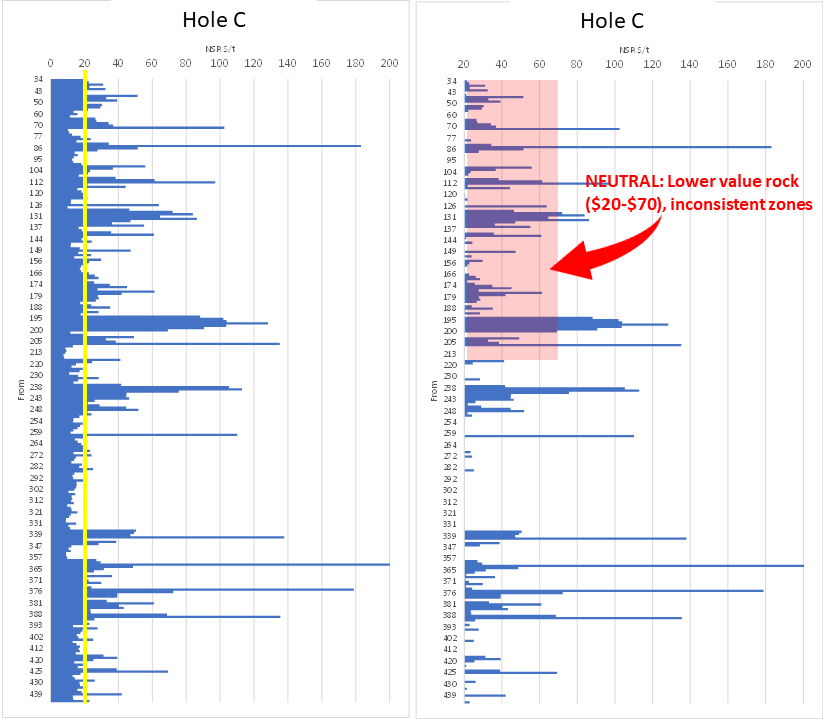

When disclosing polymetallic drill results, many companies will convert the multiple metal grades into a single equivalent grade. I am not a big proponent of that approach. The three aspects that interest me the most when looking at early-stage drill results are:

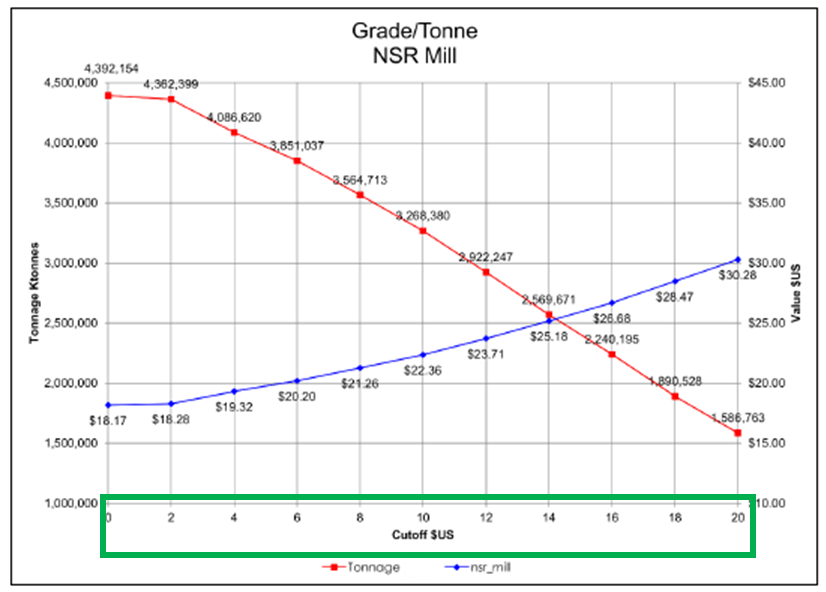

The three aspects that interest me the most when looking at early-stage drill results are: The “NSR factor” would now be 85% x 85% or 75%. Therefore, if the breakeven cost is $14/t, then one should target to mine rock with an insitu value greater than $20/tonne (i.e. $14 / 0.75). This would be the approximate ore vs waste cutoff. It is still only ballpark estimate at this early stage, but good enough for this type of review.

The “NSR factor” would now be 85% x 85% or 75%. Therefore, if the breakeven cost is $14/t, then one should target to mine rock with an insitu value greater than $20/tonne (i.e. $14 / 0.75). This would be the approximate ore vs waste cutoff. It is still only ballpark estimate at this early stage, but good enough for this type of review.

This might be better than each company applying their own unique equivalent grade calculation to their exploration results.

This might be better than each company applying their own unique equivalent grade calculation to their exploration results.

I would suggest that the three reporting categories be used instead of two, described as follows:

I would suggest that the three reporting categories be used instead of two, described as follows:

The DRX Drill Hole and Reporting algorithm developed by

The DRX Drill Hole and Reporting algorithm developed by