This is Part 2 of my story about working at a potash mine in Saskatchewan. If you haven’t read Part 1, here is the link to it “Potash Stories from 3000 Feet Down – Part 1“. It’s best to read it first.

Flooded Russian Potash Mine

As mentioned in Part 1, water seepage and potential leaks were always an operational concern. There were essentially two main fears; (i) that a borer would tunnel into an unforeseen collapse zone (i.e. an ancient sink hole) or (ii) that long term deformations in the mine would result in cracking of the overlying protective salt layer resulting in water inflow.

Any time wet spots were seen on the roof, the mining engineers or geologists were called out to take a look.

Sometimes the wet area was due to pockets of interstitial moisture. Other times it might have just been oil from a blown hydraulic hose on the borer. Wet spots all look the same when covered in dust.

Water ingress was such a concern in that an unmined pillar of 100 ft. would be left around all exploration core holes. These 3,000 ft. holes were supposedly plugged after drilling but you could never be certain of that. Furthermore, you couldn’t be certain of their location at potash depth. Hence, we didn’t want to mine anywhere close to them.

The process plant also had several water injection wells whereby excess water was injected into geological formations deep below the potash level. We left a 700 ft. pillar around these injection wells.

Carnallite is a magnesium salt that we encountered in some areas of the mine. It was weaker than the halite, resulting in more rapid room closure and deteriorating ground conditions. It was also hydroscopic and could absorb moisture out of the air. Sometimes we would water the underground travel ways to mitigate dust issues. With the resulting high humidity sometimes the carnallite areas might start to drip water. This resulted in another call to the engineers to come out and investigate.

Working on a production crew brings new learnings.

My period as a production foreman was great. When first assigned to this role, I was less than enthusiastic but when it was over 6 months later, I appreciated the opportunity. As a production foreman, we had a crew of 15 to 20 people responsible for mining 9,500 tons over a 12 hour shift. There was one foreman in the underground dispatch room and one face foreman travelling around supervising the borers and inspecting conveyors.

Ore grade control was a key responsibility of both the borer operator and mine foreman. The goal for the borer operator was to cut the roof even with the top of the high grade potash bed. The goal for the foreman was to ensure the operator was maintaining his goal. However, when looking at the potash face all the beds generally looked the same, especially when they are dusty.

Feel the glow

One key distinction was that the middle low grade bed had a higher percentage of insol clays. It was used as a marker bed. You would take your hardhat lamp and run it down against the wall. In the upper high grade potash bed, the cap lamp would have a halo, not unlike like the glowing salt rock lamps you see in stores. In the marker bed the halo would disappear, like putting a lamp against a rock wall.

Thus using the lamp you could identify the top of the marker bed, which was supposed to be kept 3.5 to 4 ft. off the floor. If borer operators were consistently more than 12 “ inches off optimal level, they could be written up (i.e. reprimanded). This was one of my tasks as foreman and I always hated doing it.

Lasers were used to guide the borer in a straight line but the marker bed was used for vertical control. Nowadays the use of machine mounted ore grade monitors is an option. By the way, if you’re looking at a potash project, be aware of the grade units being reported. A previous blog discusses this “Potash Ore Grades – Check the Units”.

The underground conveyor network consisted of 32” conveyors, feeding onto 42” conveyors, feeding on to 48”or 54” conveyors. Typically the length of the larger conveyors was in the range of a mile (5,000-6,000 ft.). The conveyors were all roof mounted, allowing for easy clean up underneath. Roof mounting was critical. Even some of the 600 hp conveyor drive stations were roof mounted, structure and all.

Conveyors were the reason for my one and only safety incident.

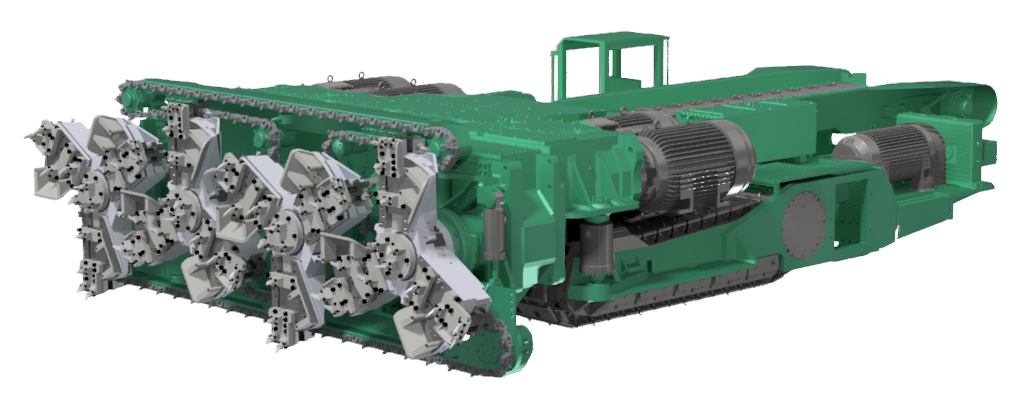

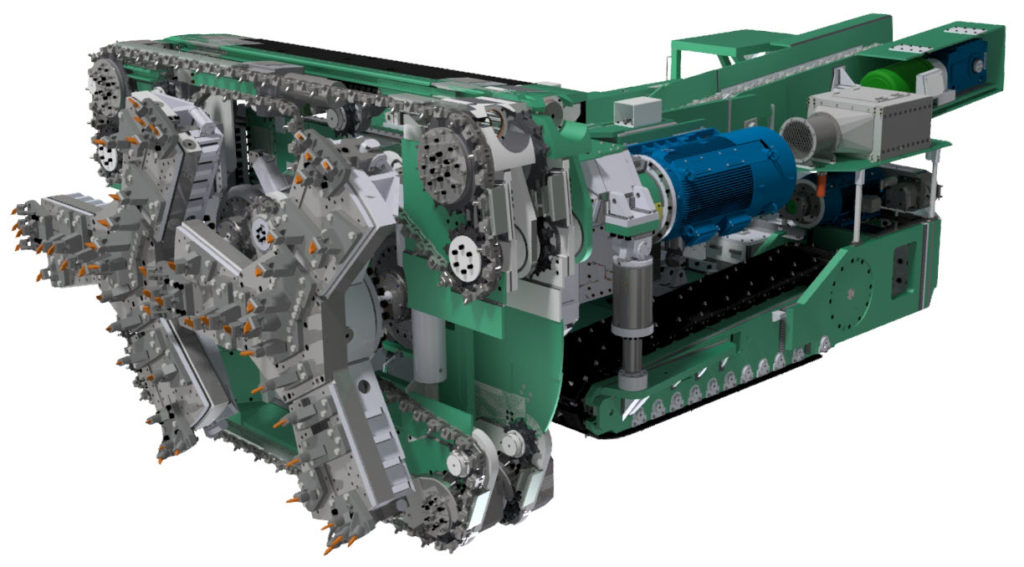

4-rotor borer side pass

First a little background. The underground ore storage capacity at K1 was about 3,000 tons. If the underground bins were filled anytime during a shift, the entire conveyor system would automatically trip off; all 10 miles of it. If you happened to have a mile long conveyor shut off while it was loaded to the brim with ore, good luck starting it up again.

If this happened, there were two choices. You could bring in the operators from the borers to start shovelling off the conveyor until it was unloaded enough to re-start. This option went over like a lead balloon with the crew.

The other not so great option was to use a scooptram to lift the belt counterweight up to reduce the belt tension. This allows the drive pulleys to start spinning. Then by lowering the counterweight back down perhaps the drives can inch the belt along. The idea being that possibly the momentum of the moving mass of potash would keep it moving. The downside is that you could break the belt. There was nothing worse than having to tell the cross shift they have both a stalled conveyor and a broken belt. Have a good shift people.

At 4 a.m. working as night shift face foreman, I knew the underground bins were nearing full. Driving along I saw that the mainline conveyor was full and spilling over the sides. A worst case conveyor shutdown was imminent. I called the dispatch office to ask why he hasn’t been shutting down borers and conveyors but there was no answer.

After several unanswered calls I started to hustle back to dispatch. I remember driving alongside the conveyor thinking “don’t shut off, don’t shut off”. Just then a heavy duty service vehicle pulled out of a cross-cut and I plowed right into it. I wasn’t going very fast (~20 km), but when a Toyota Land Cruiser hits a steel plate truck, the Toyota is the loser. The front end crumpled, and I later was told that there was major frame damage.

I’m not sure why the other driver didn’t see my lights. I’m also certain his lights were not on. Nevertheless, I did get written up for this incident with a reprimand for my personnel file. The reprimander had become the reprimandee. I still insist that the incident wasn’t my fault.

The Land Cruiser laid around the shaft for a few days until it could be hoisted up to surface. Everyone coming on shift got to see it . Once it was hoisted up, it laid outside the headframe for a few more days for all the surface workers to see. Ultimately, this incident resulted in the underground miners giving me the nickname “Crash”.

This is where I’ll end the potash story.

Conclusion

Saskatchewan potash is a unique mining situation. It has its own history and mining method. The people are great and it’s a great place to learn the difference between engineering school and real life.

Mine Engineering Dream Team

By the way, I also learned that small town Saskatchewan loves their senior hockey league (20-30 year age range). The local towns compete all winter; sometimes combatively. It was Esterhazy vs. Langenburg vs. Whitewood vs. Rocanville vs. Stockholm vs. Moosomin.

One of the first questions asked in my job interview at Mosaic was if I played hockey. You see, the ideal candidate for the job would have been an ex-NHL player, preferably an enforcer, who is also a mining engineer. Gotta stack the local team.

If you enjoy reading these types of stories about working as an engineer, there is an entire book on the subject, written by a former colleague of mine. You can learn a bit more about this civil engineer’s experiences working around the global at this link “Life as an Engineer – Read All About It”

Potash is termed a plastic rock, in that it will deform slowly under stress. Hard rock will build up stresses and erupt violently in a “rock burst”. Potash will go with the flow and deform. Pillars will compress vertically and expand horizontally. Room heights can decrease over time as much as 6 inches over several weeks in higher stress areas.

Potash is termed a plastic rock, in that it will deform slowly under stress. Hard rock will build up stresses and erupt violently in a “rock burst”. Potash will go with the flow and deform. Pillars will compress vertically and expand horizontally. Room heights can decrease over time as much as 6 inches over several weeks in higher stress areas. For a year or so, I also worked as a production foreman. It was an interesting role. How does a young mining engineer four years out of school tell guys working underground for 20 years what they need to do?

For a year or so, I also worked as a production foreman. It was an interesting role. How does a young mining engineer four years out of school tell guys working underground for 20 years what they need to do?

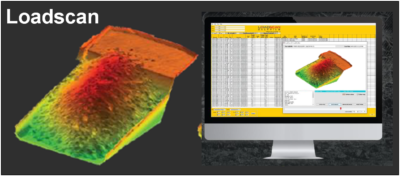

Loadscan has been around for a few years, but I only became aware of it recently. It is a technology that allows the rapid assessment of the load being carried in truck. It does not rely on the use of load cells or weigh scales to measure the payload.

Loadscan has been around for a few years, but I only became aware of it recently. It is a technology that allows the rapid assessment of the load being carried in truck. It does not rely on the use of load cells or weigh scales to measure the payload. What is interesting about this technology is that it is simple to install in an operation. It does not require retrofitting of a truck.

What is interesting about this technology is that it is simple to install in an operation. It does not require retrofitting of a truck. SedimentIQ is a new smartphone vehicle tracking platform that is trying to establish itself. Their proposed technology makes use of a phone’s built-in GPS, Bluetooth, and accelerometer to track vehicle operation. The phone’s sensor can measure vibrations produced by an operating truck or loader.

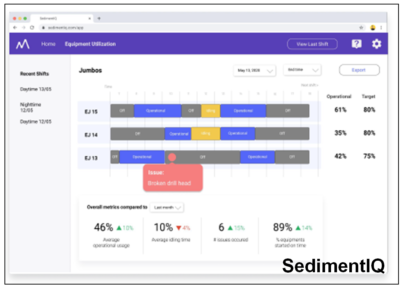

SedimentIQ is a new smartphone vehicle tracking platform that is trying to establish itself. Their proposed technology makes use of a phone’s built-in GPS, Bluetooth, and accelerometer to track vehicle operation. The phone’s sensor can measure vibrations produced by an operating truck or loader. The SedimentIQ software will aggregate the cycle time and delay information and upload it in real time to a cloud based database. A web-based dashboard allows anyone with access to view the real time production data graphically or export it to Excel.

The SedimentIQ software will aggregate the cycle time and delay information and upload it in real time to a cloud based database. A web-based dashboard allows anyone with access to view the real time production data graphically or export it to Excel.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction. There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project.

There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project. An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit.

An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit. Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time?

Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time? As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

This pessimism training started early in my career while working as a geotechnical engineer. Geotechnical engineers were always looking at failure modes and the potential causes of failure when assessing factors of safety.

This pessimism training started early in my career while working as a geotechnical engineer. Geotechnical engineers were always looking at failure modes and the potential causes of failure when assessing factors of safety. When undertaking a due diligence, particularly for a major company or financier, we are not hired to tell them how great the project is. We are hired to look for fatal flaws, identify poorly based design assumptions or errors and omissions in the technical work. We are mainly looking for negatives or red flags.

When undertaking a due diligence, particularly for a major company or financier, we are not hired to tell them how great the project is. We are hired to look for fatal flaws, identify poorly based design assumptions or errors and omissions in the technical work. We are mainly looking for negatives or red flags. It has been my experience that digging in a data room or speaking with the engineering consultants can reveal issues not identifiable in a 43-101 report. Possibly some of these issues were mentioned or glossed over in the report, but you won’t understand the full extent of the issues until digging deeper.

It has been my experience that digging in a data room or speaking with the engineering consultants can reveal issues not identifiable in a 43-101 report. Possibly some of these issues were mentioned or glossed over in the report, but you won’t understand the full extent of the issues until digging deeper. My hesitance in investing in some companies unfortunately can be penalizing. I may end up sitting on the sidelines while watching the rising stock price. Junior mining investors tend to be a positive bunch, when combined with good promotion can result in investors piling into a stock.

My hesitance in investing in some companies unfortunately can be penalizing. I may end up sitting on the sidelines while watching the rising stock price. Junior mining investors tend to be a positive bunch, when combined with good promotion can result in investors piling into a stock. Most times the issue is something we couldn’t fully address given the level of study. We might have been forced to make best guess assumptions to move forward. The review engineers will have their opinions about what assumptions they would have used. Typically the common comment is that our assumption is too optimistic and their assumption would have been more conservative or realistic (in their view).

Most times the issue is something we couldn’t fully address given the level of study. We might have been forced to make best guess assumptions to move forward. The review engineers will have their opinions about what assumptions they would have used. Typically the common comment is that our assumption is too optimistic and their assumption would have been more conservative or realistic (in their view).

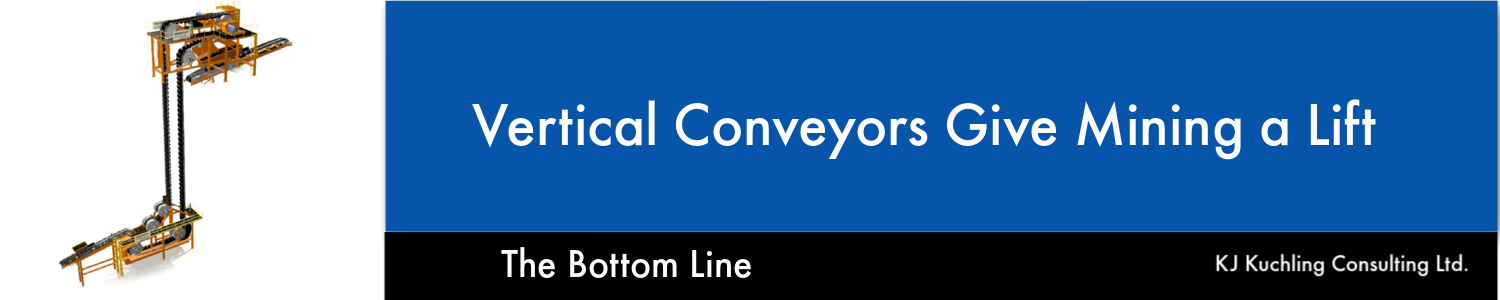

The background information on vertical conveying was provided to me by FKC-Lake Shore, a construction contractor that installs these systems. FKC itself does not fabricate the conveyor hardware. A link to their website is

The background information on vertical conveying was provided to me by FKC-Lake Shore, a construction contractor that installs these systems. FKC itself does not fabricate the conveyor hardware. A link to their website is  The FLEXOWELL®-conveyor system is capable of running both horizontally and vertically, or any angle in between. These conveyors consist of FLEXOWELL®-conveyor belts comprised of 3 components: (i) Cross-rigid belt with steel cord reinforcement; (ii) Corrugated rubber sidewalls; (iii) transverse cleats to prevent material from sliding backwards. They can handle lump sizes varying from powdery material up to 400 mm (16 inch). Material can be raised over 500 metres with reported capacities up to 6,000 tph.

The FLEXOWELL®-conveyor system is capable of running both horizontally and vertically, or any angle in between. These conveyors consist of FLEXOWELL®-conveyor belts comprised of 3 components: (i) Cross-rigid belt with steel cord reinforcement; (ii) Corrugated rubber sidewalls; (iii) transverse cleats to prevent material from sliding backwards. They can handle lump sizes varying from powdery material up to 400 mm (16 inch). Material can be raised over 500 metres with reported capacities up to 6,000 tph. Vendors have evaluated the use of vertical conveying against the use of a conventional vertical shaft hoisting. They report the economic benefits for vertical conveying will be in both capital and operating costs.

Vendors have evaluated the use of vertical conveying against the use of a conventional vertical shaft hoisting. They report the economic benefits for vertical conveying will be in both capital and operating costs. The vendors indicate the conveying system should be able to achieve heights of 700 metres. This may facilitate the use of internal shafts (winzes) to hoist ore from even greater depths in an expanding underground mine. It may be worth a look at your mine.

The vendors indicate the conveying system should be able to achieve heights of 700 metres. This may facilitate the use of internal shafts (winzes) to hoist ore from even greater depths in an expanding underground mine. It may be worth a look at your mine.

Based on my own career, mining has definitely provided me with a chance to travel the world. It will also help anyone overcome their fear of travel. One will also learn that both international and domestic travel can be as equally rewarding. There is nothing wrong with learning more about your own country.

Based on my own career, mining has definitely provided me with a chance to travel the world. It will also help anyone overcome their fear of travel. One will also learn that both international and domestic travel can be as equally rewarding. There is nothing wrong with learning more about your own country.

Business travel has always been one of the best parts of my mining career. I can remember the details about a lot of the travel that I did. Unfortunately the project details themselves will blur with those of other projects.

Business travel has always been one of the best parts of my mining career. I can remember the details about a lot of the travel that I did. Unfortunately the project details themselves will blur with those of other projects.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy. With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation.

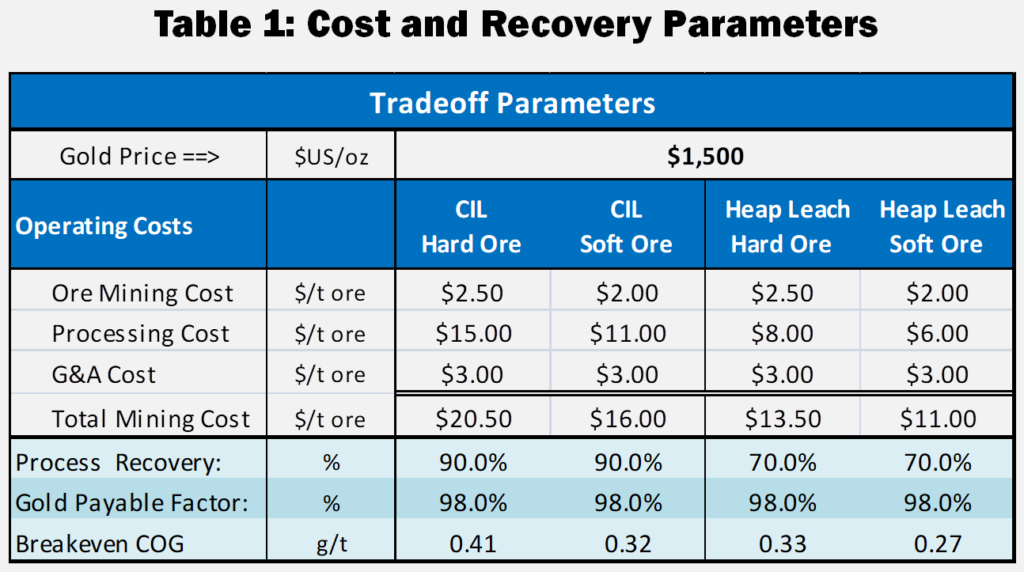

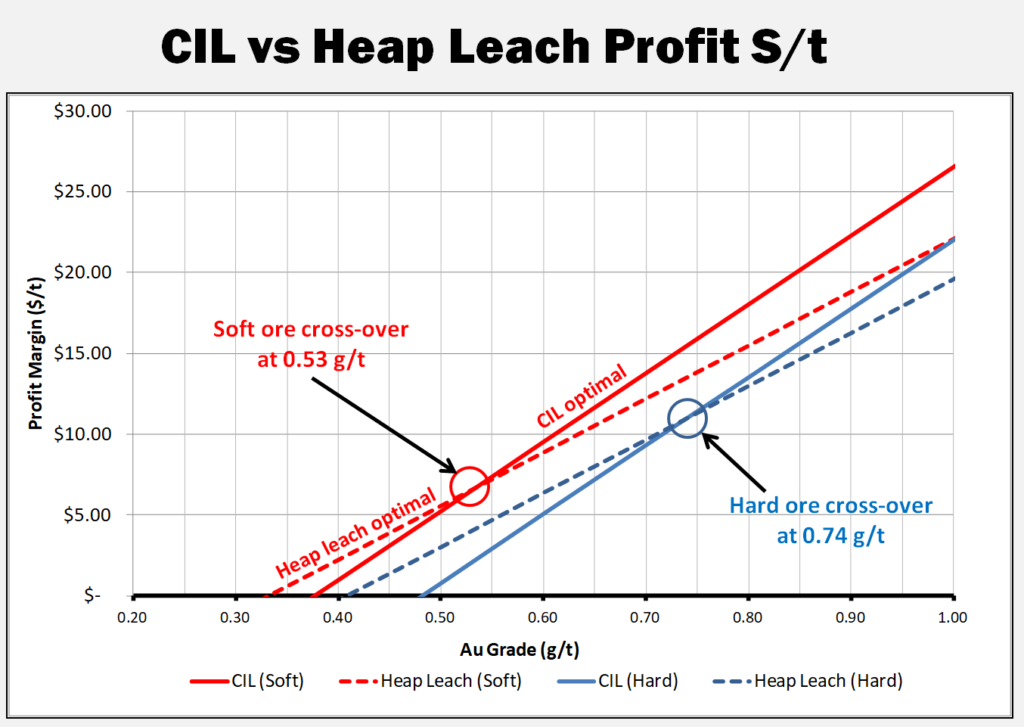

With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation. I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz.

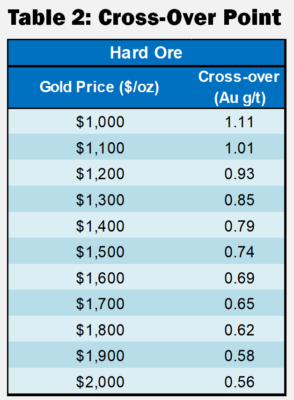

I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz. These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

Normally I don’t write about mining stock markets, preferring instead to focus on technical matters. However I have seen some recent discussions on Twitter about stock price trends. For every stock there are a wide range of price expectations. Ultimately some of the expectations and realizations can be linked back to the Lassonde Curve.

Normally I don’t write about mining stock markets, preferring instead to focus on technical matters. However I have seen some recent discussions on Twitter about stock price trends. For every stock there are a wide range of price expectations. Ultimately some of the expectations and realizations can be linked back to the Lassonde Curve.

Stage 5 is the start-up and commercial production period, possibly nerve-racking for some investors. This is where the rubber hits the road. The stock price can fall if milled grades, operating costs, or production rates are not as expected.

Stage 5 is the start-up and commercial production period, possibly nerve-racking for some investors. This is where the rubber hits the road. The stock price can fall if milled grades, operating costs, or production rates are not as expected. Some corporate presentations will highlight the Lassonde Curve, particularly when they are rising in Stage 1. You are less likely to see the curve presented when they are rolling along in Stages 2 or 3.

Some corporate presentations will highlight the Lassonde Curve, particularly when they are rising in Stage 1. You are less likely to see the curve presented when they are rolling along in Stages 2 or 3.

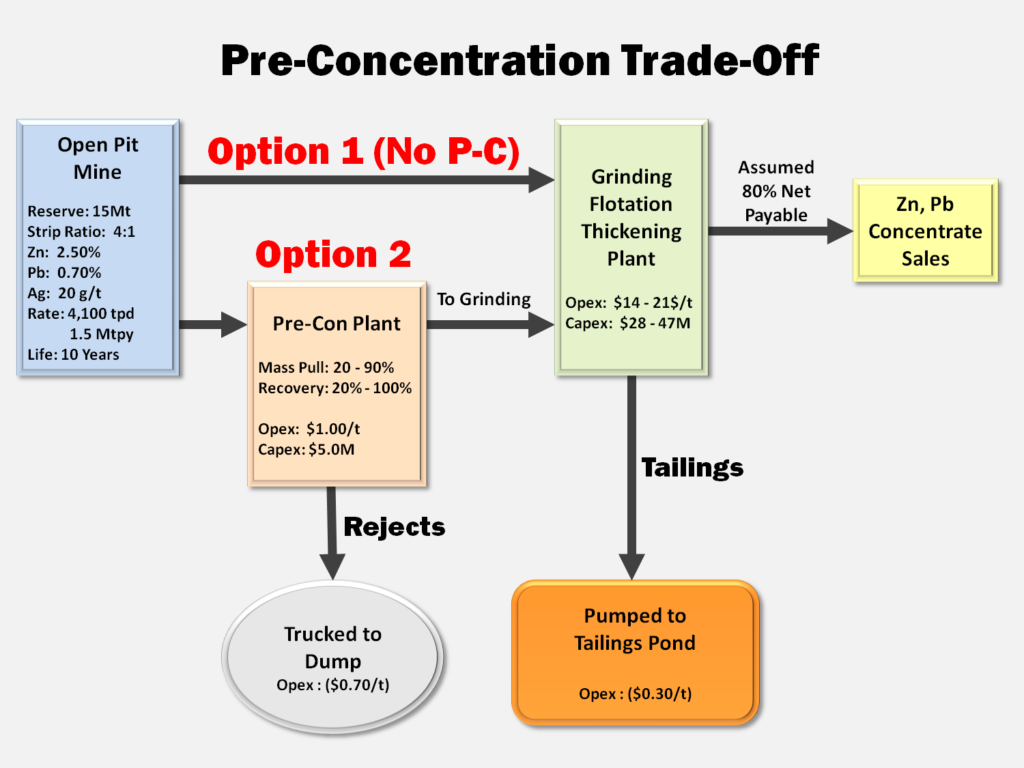

Concentrate handling systems may not differ much between model options since roughly the same amount of final concentrate is (hopefully) generated.

Concentrate handling systems may not differ much between model options since roughly the same amount of final concentrate is (hopefully) generated.

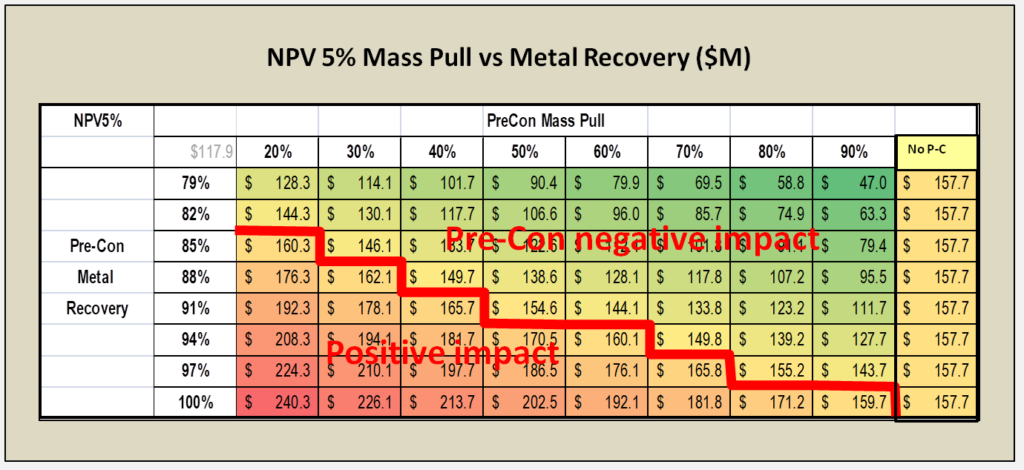

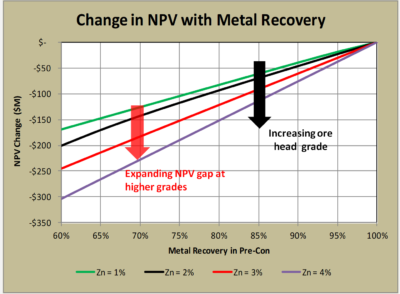

4. The head grade of the deposit also determines how economically risky pre-concentration might be. In higher grade ore bodies, the negative impact of any metal loss in pre-concentration may be offset by accepting higher cost for grinding (see chart on the right).

4. The head grade of the deposit also determines how economically risky pre-concentration might be. In higher grade ore bodies, the negative impact of any metal loss in pre-concentration may be offset by accepting higher cost for grinding (see chart on the right).