In my view, one of the most important things you need to understand about your orebody is the insitu rock value. Hopefully it is economic, i.e. an ore value. Its the key driver in shaping the economics of any mining project.

The two main nature-driven factors in the economics of a mining project are the ore grade and the ore tonnage. In simplistic terms, the ore grade will determine how much incremental profit can be generated by each tonne of rock processed.

The two main nature-driven factors in the economics of a mining project are the ore grade and the ore tonnage. In simplistic terms, the ore grade will determine how much incremental profit can be generated by each tonne of rock processed.

The ore tonnage will determine whether the cumulative profit generated all the ore will be sufficient to pay back the project’s capital investment plus provide some reasonable profit to the owner.

Does the Ore Grade Generate a Profit ?

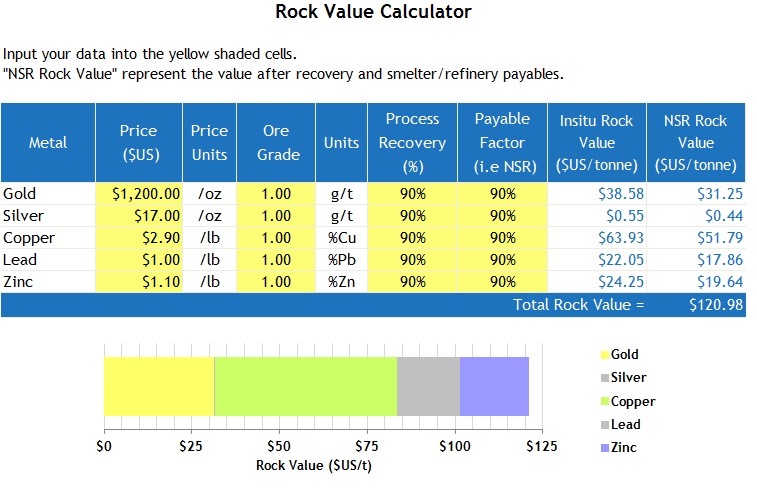

In order to understand the incremental profit generated by each ore tonne one must first convert the ore grade into a revenue dollar value. This calculation will obviously depend on metal prices and the amount of metal recovered. For some deposits with multiple metals, the total revenue per tonne will be based on the summation of value contributed by each metal. Some metals may have different process recoveries and different net smelter payable factors, so several factors come into play.

To help calculate the value of the insitu ore, I have created a simple cloud-based spreadsheet at this link (Rock Value Calculator). An example screenshot is shown below. Simply enter your own data in the yellow shaded cells and the rock values are calculated on a “$ per tonne” basis. since the table is pre-populated, one must zero out the values for metals of no interest.

Price: represents the metal prices, in US dollars for the metals of interest.

Ore Grade: represents that head grades for the metals of interest in the units as shown (g/t and %).

Process Recovery: represents the average % recovery for each of the metals of interest.

Payable Factor: represents the net payable percentage after various treatment, smelting, refining, penalty charges. This is simply an estimate depending on the specific products produced at site. For example, concentrates would have an overall lower payable factor than say gold-silver dore production.

Insitu Rock Value: this output is the dollar value of the insitu rock (in US dollars), without any process recovery or payable factors being applied.

NSR Rock Value: this output represents the net smelter return dollar value after applying the recovery and payable factors. This represents the actual revenue that could be generated and used to pay back operating costs. One can see the impact that these payables have on the overall value.

Mining Profit = Revenue – Cost

The final profit margin will be determined by subtracting the mine operating cost from the NSR Rock Value. These operating costs would include mining, processing, G&A, and some offsite costs. Typically large capacity open pit operations may have total operating costs in the range of $10-15/tonne, while conventional hardrock underground operations would be much higher ($50->$100/t).

Conclusion

The bottom line is that very early on one should understand the net revenue that your project’s head grades may deliver. How valuable is the rock? It is a fairly simple calculation to undertake.

You can even start evaluating the rock at the exploration drilling stage. I have a cloud-based calculator for this at the link “Drill Intercept Analysis“. This calculator is a bit more complex than the Rock Value Calculation but relies on inputting drill intercept data.

Ore value will give sense for whether its a high margin project or whether the ore grades are marginal and higher metal prices or low operating costs will be required. The earlier one understands the potential economics of the different ore types, the better one will be able to visualize, design, and advance the project.

For gold deposits, I have another blog post that discusses grades, values, and how they related to open pit or underground mining costs. Low grade narrow intervals like have much less economic potential than wide low grade interval or narrow high grade gold intervals. You can read that post at this link “Gold Exploration Intercepts – Interesting or Not?“

Note: If you would like to get notified when new blogs are posted, then sign up on the KJK mailing list on the website. Otherwise I post notices on LinkedIn, so follow me at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kenkuchling/.

In my personal experience I find that larger consultants are best suited for managing the large scale feasibility studies. This isn’t because they necessarily provide better technical expertise. Its because they generally have the internal project management and costing systems to manage the complexities of such larger studies.

In my personal experience I find that larger consultants are best suited for managing the large scale feasibility studies. This isn’t because they necessarily provide better technical expertise. Its because they generally have the internal project management and costing systems to manage the complexities of such larger studies. For certain aspects of a feasibility study, one may get better technical expertise by subcontracting to smaller highly specialized engineering firms. However too much subcontracting may become an onerous task. Often the larger firms may be better positioned to do this.

For certain aspects of a feasibility study, one may get better technical expertise by subcontracting to smaller highly specialized engineering firms. However too much subcontracting may become an onerous task. Often the larger firms may be better positioned to do this. One of the purposes of an early stage study is to see if the project has economic merit and would therefore warrant further expenditures in the future. An early stage study is (hopefully) not used to defend a production decision. The objective of an early stage study is not necessarily to terminate a project (unless it is obviously highly uneconomic).

One of the purposes of an early stage study is to see if the project has economic merit and would therefore warrant further expenditures in the future. An early stage study is (hopefully) not used to defend a production decision. The objective of an early stage study is not necessarily to terminate a project (unless it is obviously highly uneconomic).

Some of the models I have reviewed will build the entire operating cost (mining, processing, G&A) in one grand file. They will build in the capital cost too and finally provide the economic model… all in one spreadsheet!

Some of the models I have reviewed will build the entire operating cost (mining, processing, G&A) in one grand file. They will build in the capital cost too and finally provide the economic model… all in one spreadsheet!