Several years ago I worked in the Saskatchewan potash industry where I grew my appreciation for continuous mining systems. Some of the key benefits were the high productivity per man-hour and the safe operating conditions. On a 12 hour nightshift, with a crew of 16 people we could mine over 9,000 tonnes of ore. Productivity is likely even higher now with the larger machines. Therefore, since that time, I have always kept an eye out for when similar technology can be applied in hard rock mining.

One of the research areas we are seeing these days is the development of continuous cutting technology for hard rock mine development. The idea is to replace the conventional drill & blast approach with something more efficient and safer. No need to deal with explosives, noxious gases, shatter the wall rock, or have personnel scale their way under loose conditions.

Recently I was contacted by someone associated with Robbins asking if I was aware of their MDM5000 mine development technology. I wasn’t aware of it, but I wondered if there finally is a light at the end of the tunnel.

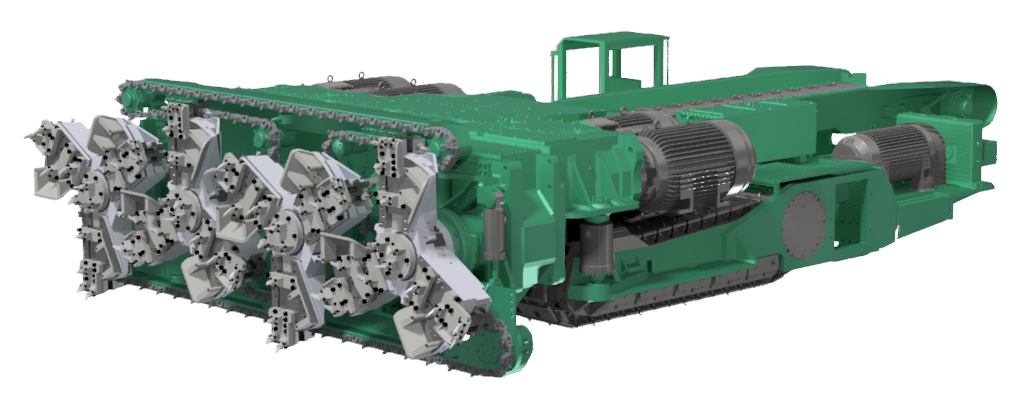

4-rotor miner

In Saskatchewan potash the entire mining operation relies on track-mounted continuous miner technology. The miners are connected directly to the shaft area using a network of conveyors, up to 10 km worth of conveyor.

The potash miners are able to undertake both development work and production mining whilst connected to conveyor.

From time to time they will rely on shuttle cars, scooptrams, or grasshopper conveyors for small development tasks. A roadheader may also be available for localized ground stabilization.

All of this mechanical cutting is done in potash (sylvinite rock), considered a soft rock with a compressive strength of 20-40 MPa. For comparison, hard rock can have compressive strengths exceeding 250 MPa.

Two approaches in hard rock

Hard rock piloting trials are underway at a few operations, using different vendors with different equipment. These trials include companies like Komatsu, Robbins, Sandvik, and Epiroc. Each are testing their own equipment and cutting technologies.

The hard rock cutting approaches generally fall into two camps.

Roadheader style

There are the track mounted roadheader style cutters, typically with a movable arm used to shape the excavation. Any excavation shape is possible.

Tunnel Borer Style

Then there are the tunnel borer styles, where the machine propels itself with hydraulic shoes and the opening shape is based on the machine configuration. Normally a circular shaped opening is the result.

The roadheader style cutter is normally restricted to softer rock (< 50 MPa) while the tunnel borer is capable of much harder rock (200-250 MPa).

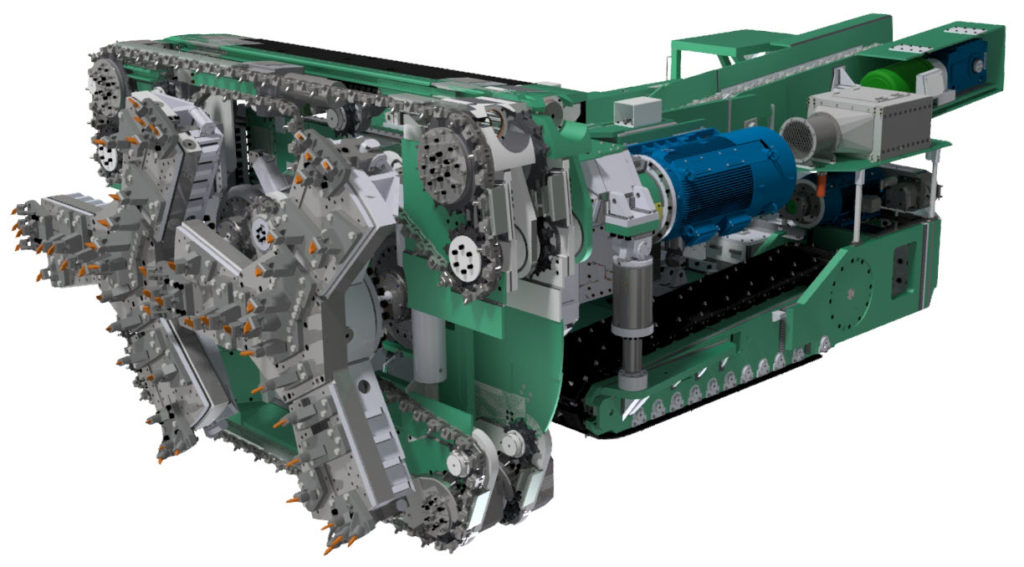

Robbins MDM5000

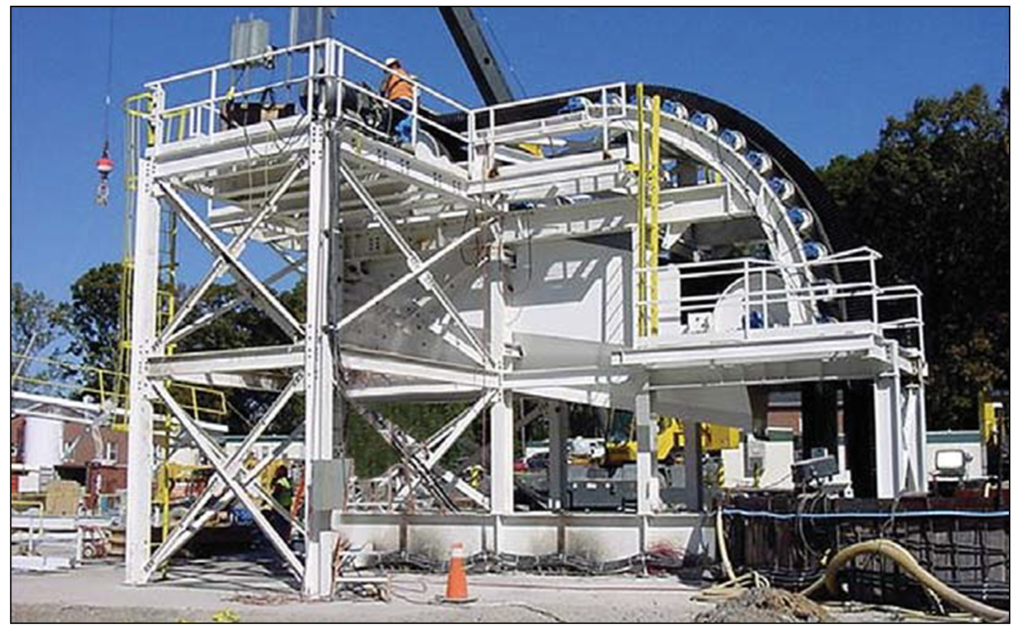

One system that peaked my interest is the Robbins MDM5000 because it can both cut hard rock and create a rectangular opening. Speaking with the vendor, this unit uses shoes to propel itself while cutting a rectangular shaped opening about 5m x 4.5m in size (see image). A rectangular shape is preferred to the circular opening whereby the floor invert must be backfilled to provide a level operating surface.

MDM5000 opening shape

The MDM5000 configuration and advance rate allows the installation of ground support and utilities behind the advancing face. Water sprays and dust collectors help to maintain visibility and air quality at the working face.

The Robbins unit is best suited for long straight drives although reportedly it can turn curves with 450-m radius. Tighter turns may be feasibility in the future by tweaking the machine design. Interestingly driving a drift uphill is easier than driving downhill due to the more efficient cuttings removal capability.

The MDM5000 unit can be linked to a Robbins conveyor system, which includes a head drive and an extensible belt storage unit that can feed out the conveyor belt as the machine advances forward. This operation is similar to that used in the Saskatchewan potash industry.

Robbins MDM5000

A Robbins machine has been in operation at the Fresnillo mine for several years with favorable results (check out the link here).

One nice thing about disc cutters is that they can accommodate variable rock types (softer and harder) while road headers can be hindered by hard rock zones. Roadheaders require a bit more consistency in rock quality.

Continuous cutting systems, such as the MDM5000, can be combined with vertical conveying technology, leading to safe and rapid development (>200m per month) in the right situation.

Conclusion

No doubt that we will eventually see more application of hard rock continuous cutting technology in the right situations. The Stillwater Mine in Montana has been using a Robbins tunnel borer for years for development tasks.

No matter how well these new systems perform, there will still be some limitations. This means the conventional drill and blast development will always be around. However, keep your eyes on this mining technology sector as improvements in cutter head design and equipment mobility continue to evolve.

Coincidentally International Mining (Nov-Dec 2021) recently published an in-depth article on the various systems being looked at. The link is here.

Potash is termed a plastic rock, in that it will deform slowly under stress. Hard rock will build up stresses and erupt violently in a “rock burst”. Potash will go with the flow and deform. Pillars will compress vertically and expand horizontally. Room heights can decrease over time as much as 6 inches over several weeks in higher stress areas.

Potash is termed a plastic rock, in that it will deform slowly under stress. Hard rock will build up stresses and erupt violently in a “rock burst”. Potash will go with the flow and deform. Pillars will compress vertically and expand horizontally. Room heights can decrease over time as much as 6 inches over several weeks in higher stress areas. For a year or so, I also worked as a production foreman. It was an interesting role. How does a young mining engineer four years out of school tell guys working underground for 20 years what they need to do?

For a year or so, I also worked as a production foreman. It was an interesting role. How does a young mining engineer four years out of school tell guys working underground for 20 years what they need to do?

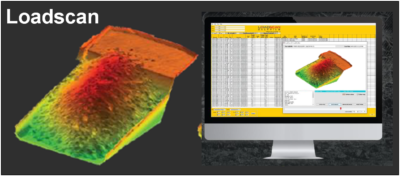

Loadscan has been around for a few years, but I only became aware of it recently. It is a technology that allows the rapid assessment of the load being carried in truck. It does not rely on the use of load cells or weigh scales to measure the payload.

Loadscan has been around for a few years, but I only became aware of it recently. It is a technology that allows the rapid assessment of the load being carried in truck. It does not rely on the use of load cells or weigh scales to measure the payload. What is interesting about this technology is that it is simple to install in an operation. It does not require retrofitting of a truck.

What is interesting about this technology is that it is simple to install in an operation. It does not require retrofitting of a truck. SedimentIQ is a new smartphone vehicle tracking platform that is trying to establish itself. Their proposed technology makes use of a phone’s built-in GPS, Bluetooth, and accelerometer to track vehicle operation. The phone’s sensor can measure vibrations produced by an operating truck or loader.

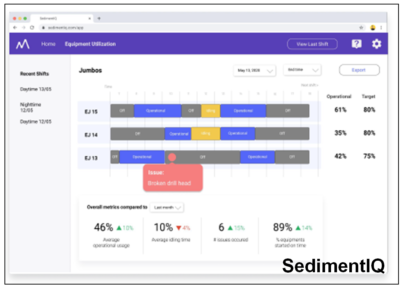

SedimentIQ is a new smartphone vehicle tracking platform that is trying to establish itself. Their proposed technology makes use of a phone’s built-in GPS, Bluetooth, and accelerometer to track vehicle operation. The phone’s sensor can measure vibrations produced by an operating truck or loader. The SedimentIQ software will aggregate the cycle time and delay information and upload it in real time to a cloud based database. A web-based dashboard allows anyone with access to view the real time production data graphically or export it to Excel.

The SedimentIQ software will aggregate the cycle time and delay information and upload it in real time to a cloud based database. A web-based dashboard allows anyone with access to view the real time production data graphically or export it to Excel.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction.

The majority of mining projects tend to consist of either open pit only or underground only operations. However there are instances where the orebody is such that eventually the mine must transition from open pit to underground. Open pit stripping ratios can reach uneconomic levels hence the need for the change in direction. There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project.

There are several reasons why open pit and underground can be considered as two different projects within the same project. An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit.

An underground mine that uses a backfilling method will be able to dispose of some tailings underground. Conversely moving towards a larger open pit will require a larger tailings pond, larger waste dumps and overall larger footprint. This helps make the case for underground mining, particularly where surface area is restricted or local communities are anti-open pit. Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time?

Open pit and underground operations will require different skill sets from the perspective of supervision, technical, and operations. Underground mining can be a highly specialized skill while open pit mining is similar to earthworks construction where skilled labour is more readily available globally. Do local people want to learn underground mining skills? Do management teams have the capability and desire to manage both these mining approaches at the same time? As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

As you can see from the foregoing discussion, there are a multitude of factors playing off one another when examining the open pit to underground cross-over point. It can be like trying to mesh two different projects together.

The background information on vertical conveying was provided to me by FKC-Lake Shore, a construction contractor that installs these systems. FKC itself does not fabricate the conveyor hardware. A link to their website is

The background information on vertical conveying was provided to me by FKC-Lake Shore, a construction contractor that installs these systems. FKC itself does not fabricate the conveyor hardware. A link to their website is  The FLEXOWELL®-conveyor system is capable of running both horizontally and vertically, or any angle in between. These conveyors consist of FLEXOWELL®-conveyor belts comprised of 3 components: (i) Cross-rigid belt with steel cord reinforcement; (ii) Corrugated rubber sidewalls; (iii) transverse cleats to prevent material from sliding backwards. They can handle lump sizes varying from powdery material up to 400 mm (16 inch). Material can be raised over 500 metres with reported capacities up to 6,000 tph.

The FLEXOWELL®-conveyor system is capable of running both horizontally and vertically, or any angle in between. These conveyors consist of FLEXOWELL®-conveyor belts comprised of 3 components: (i) Cross-rigid belt with steel cord reinforcement; (ii) Corrugated rubber sidewalls; (iii) transverse cleats to prevent material from sliding backwards. They can handle lump sizes varying from powdery material up to 400 mm (16 inch). Material can be raised over 500 metres with reported capacities up to 6,000 tph. Vendors have evaluated the use of vertical conveying against the use of a conventional vertical shaft hoisting. They report the economic benefits for vertical conveying will be in both capital and operating costs.

Vendors have evaluated the use of vertical conveying against the use of a conventional vertical shaft hoisting. They report the economic benefits for vertical conveying will be in both capital and operating costs. The vendors indicate the conveying system should be able to achieve heights of 700 metres. This may facilitate the use of internal shafts (winzes) to hoist ore from even greater depths in an expanding underground mine. It may be worth a look at your mine.

The vendors indicate the conveying system should be able to achieve heights of 700 metres. This may facilitate the use of internal shafts (winzes) to hoist ore from even greater depths in an expanding underground mine. It may be worth a look at your mine.

His topic is interesting and relevant to today’s mining industry. Paul raised many thoughtful points supported by data. He gave me permission to share his information.

His topic is interesting and relevant to today’s mining industry. Paul raised many thoughtful points supported by data. He gave me permission to share his information. I agree with many of the points raised by Paul in his study. The mining industry has some credibility issues based on recent performance and therefore understanding the causes and then repairing that credibility will be important for the future.

I agree with many of the points raised by Paul in his study. The mining industry has some credibility issues based on recent performance and therefore understanding the causes and then repairing that credibility will be important for the future.