So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some.

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some.

Now what to do? Its time to jump into NPV repair mode.

Hopefully this blog post isn’t too controversial but will lead to some discussion about how studies are done. Its based on observations I have made over the years as to what different studies will do to try to improve their economics.

The first thought typically is to lower (i.e. low ball) the capital and operating costs. We know that will certainly improve the economics. A risk with that is it might discredit the entire study if the costs are not in line with similar projects. Perhaps someone does a deep dive into the costing details or does some benchmarking against other projects. Also, advanced studies will develop more accurate costs, ultimately highlighting that the initial study was inaccurate and misleading. So overly optimistic, under-estimated costing is not a good approach.

What other things can help bump up the NPV? Let’s look at some of the ones I have seen, some of which I have applied in my work. I would expect (and hope) that some of these ideas will already have been adopted in the initial engineering and cashflow model.

Using the Time Value of Money

The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates.

The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates.

Hence looking at ways to bring revenue forward or push costs backwards are typically the first options considered. Here are a few of the ways this will be done.

High Grading and Stockpiling: One can bring revenue forward by using a Low Grade Ore stockpiling strategy. Select an elevated cutoff grade to define High Grade Ore and send only that ore to the plant. The Low Grade Ore can be placed into a stockpile and processed gradually or all at once at the end of the mine life. One must mine more tonnes to undertake stockpiling and will eventually incur an ore rehandling cost. However, in my experience, the early revenue benefit from high grade normally outweighs the associated cost impacts.

Stockpiling Tramming: If using the stockpiling approach described above, many assume that all stockpile rehandling to the crusher will simply be done by tramming with a wheel loader. Having to re-load the ore into trucks will cost more than double the cost of tramming. So place the ore stockpiles close to the crusher to lower rehandling costs.

Milling Soft Ore: If the deposit has both an upper soft ore (oxide, saprolite) and a deeper hard ore, one can take advantage of the soft material and push more ore tonnage through the plant at start-up. This will increase the up-front revenue. It may also allow the cost deferral of some plant components that are only needed for processing the harder ore.

Defer Stripping Tonnages: Delaying some waste stripping costs from pre-production (Y-1) to Year 1 or Year 2 will help improve the NPV. However, care must be taken that increasing mining tonnages in Year 1 or 2 doesn’t trigger the purchase of additional loaders and trucks. The deferred tonnes need to be small enough not to trigger a fleet size increase or could negate the impact of the cost deferral.

Capitalize Waste Stripping: It may be possible to capitalize waste stripping for satellite pits and pit wall pushbacks to better align stripping costs with the timing of ore mining. Capitalizing waste stripping may result in lower short term taxable income since the entire expense is not immediately deducted. This can reduce tax liabilities and improve cash flow. Each situation may be unique.

Accelerate Depreciation: In some jurisdictions, tax laws permit accelerated depreciation rates. This will help to lower or eliminate taxable income in the early years. This boosts the after-tax cashflow in those years, bumping up the NPV. If accelerated depreciation is the case, enhancing revenue (by high grading) at the same time, gives an even bigger nudge to the NPV. Maximize the revenue during tax free periods.

Apply Tax Losses: On some projects there are historical corporate tax loss carry-overs. These losses allow one to offset future taxes payable in the early years. This help bump up the initial after-tax cashflows.

Leasing of Equipment: One can look at equipment leasing to defer some of the initial capital costs. Leasing will distribute the purchase cost over several years (typically 60 months). Although the lease interest will increase the total cost of the machine, the capital cost deferral likely results in an NPV benefit.

Use Contract Mining: To avoid the entire cost of purchasing major mining equipment, many will look to contract mining. In studies, sometimes contract mining costs are estimated or they can be derived from budgetary contractor quotes. At an early stage these contractor quotes might be quite “favorable” as the contractor tries to stay in the good books of the mining company. Contract mining will greatly reduce the mining equipment capital cost and can help the NPV, even if the unit mining costs may be slightly higher with a contractor.

Using Other Cashflow Tweaks

There are other tweaks that one can m ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen.

ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen.

Increase Metal Prices: Normally when selecting metal prices for the cashflow model one looks at; trailing averages; analyst consensus forecasts; marketing study forecasts; and prices being used in other current studies. It is usually simple to defend whatever price you wish to use. In a rising price environment, one can see what other recent studies have used and escalate those prices by 5%-10%. That likely won’t be viewed as unreasonable. After all, someone has to be the trailblazer in raising modelling metal prices.

Improve metal recoveries: At an early study stage, one may have limited number of metallurgical tests upon which to base the process recoveries. I have seen some bump up the recoveries slightly and add the statement “Further metallurgical testing, grind size optimization, and reagent optimization should improve the recovery above those shown by the current test work”. This can gain a bit of revenue at no extra cost.

Optimistic Dilution: It can be very difficult to predict ore mining dilution at an early stage. Two different engineers looking at he same mining method, may come up with different dilution assumptions. Hence one may have the opportunity to select an optimistic dilution. Lower dilution will increase the head grade to the mill and hence increase the revenue at no extra cost. Even a modest reduction in dilution will play its role in nudging up the NPV.

Reduction in Working Capital: Some cashflow models do not include the cost for working capital, while others will include it. Working capital is the money needed on hand to pay the monthly operating cost in Year 1 before payable revenue is generated. If difficulties arise in achieving commercial production, one wishes to have more working capital on hand. Working capital typical is 2-4 months of operating cost. To bump up NPV, some will use the lower range of 2 months working capital. Some will just omit working capital entirely. Take a look at the working capital needs and decide what is reasonable.

Buy the Royalty: Some projects may have the option for a company to buy out the royalty from the royalty holder. Although doing this may result in an upfront cost, the payable royalty saving may offset that up-front buy-out cost. At high metal prices, the royalty saving could be significant.

Reclamation Cost Equals Salvage Value: At the end of the mine life, the final closure and reclamation cost will be in the tens of millions of dollars. Although this cost is heavily discounted back to the start of the cashflow model, I have seen cases where it is assumed that salvage value of the mine and plant equipment is sufficient to pay the entire closure cost. I don’t know how realistic this is, but I have seen that assumption used.

Lower The Discount Rate: A few years ago, it seems the benchmark discount rate was 5% used in most studies. In 2024, the cost of capital has gone up. Hence many studies seem to be using 8%-10% as their base case. A project at the PEA stage today isn’t going to be built for a few years. Some can argue that interest rates will likely be lower in a few years, and so using 5% discount rate today is still reasonable. Conversely some will maintain that is is best to use what others are using so that current projects are all comparable.

Conclusion

Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times. Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant.

Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant. Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate. These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers.

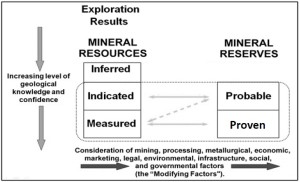

So I thought what better way to explain the mining engineer role than by describing the anatomy of a typical Chapter 16 (MINING) in a 43-101 Technical Report. That chapter is a good example of the range of tasks typically undertaken by mining engineers. There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work.

There is always a mineral resource estimate available before doing a PEA. The way the resource is reported will indicate what type of mine this likely is. The geologists have already done some of the mining engineer’s work. Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type.

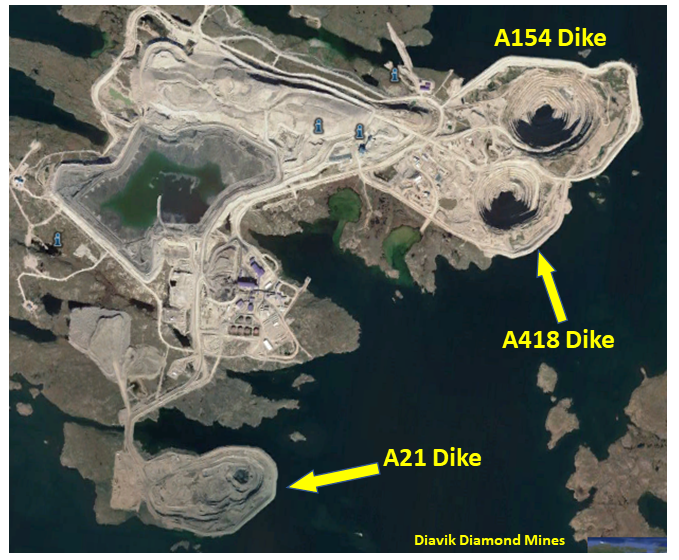

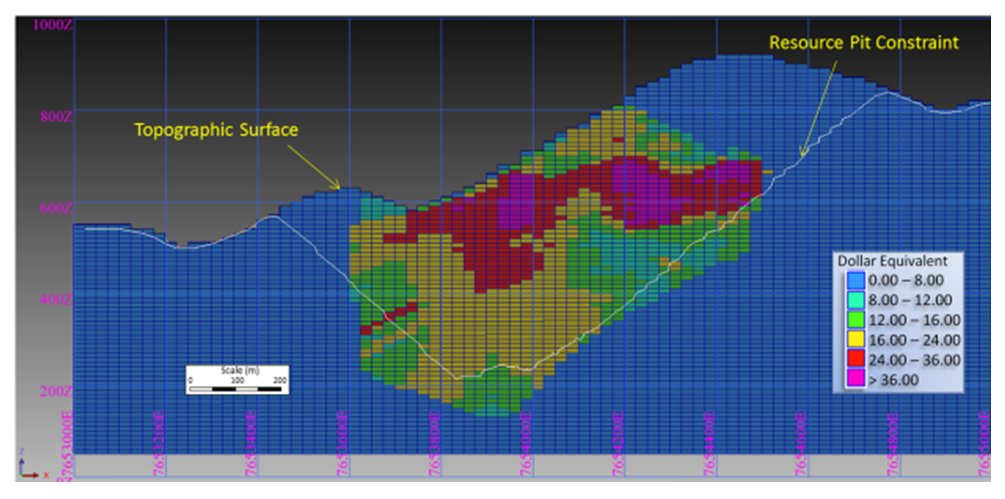

Before starting pit optimization, we require economic inputs from several people. The base case metal prices must be selected (normally with input from the client). The mining operating cost per tonne must be estimated (by the mining engineer). The processing engineers will provide the processing cost and recovery for each ore type. Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal.

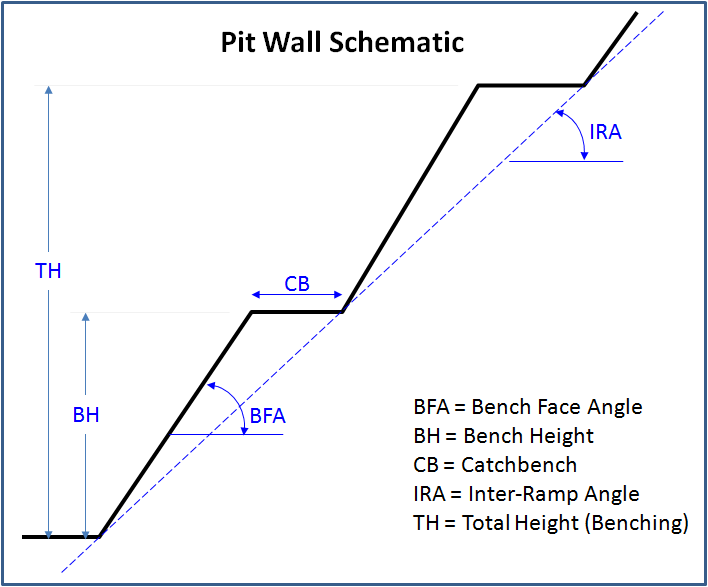

Once the optimization is run, a series of nested pit shells are created, each with its own tonnes and grade. These shells are compared for incremental strip ratio, incremental head grade, total tonnes, and contained metal. The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

The mining engineer is now ready to undertake the pit design. The pit design step introduces a benched slope profile, smooths out the pit shape, and adds haulroads. Hence a couple of key input parameters are required at this time. The mining engineer will need to know the geotechnical pit slope criteria and the truck size & haul road widths. Let’s look at both of these.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created.

Ramps: Next the mining engineer needs to select the truck size, even though the production schedule has not yet been created. This ends Part 1. In Part 2 we will discuss the mining engineer’s next tasks; production scheduling; waste dump design; and equipment selection. The mining engineer QP will sign off and take responsibility for all the mine design work done so far. You can read Part 2 at this link “

This ends Part 1. In Part 2 we will discuss the mining engineer’s next tasks; production scheduling; waste dump design; and equipment selection. The mining engineer QP will sign off and take responsibility for all the mine design work done so far. You can read Part 2 at this link “

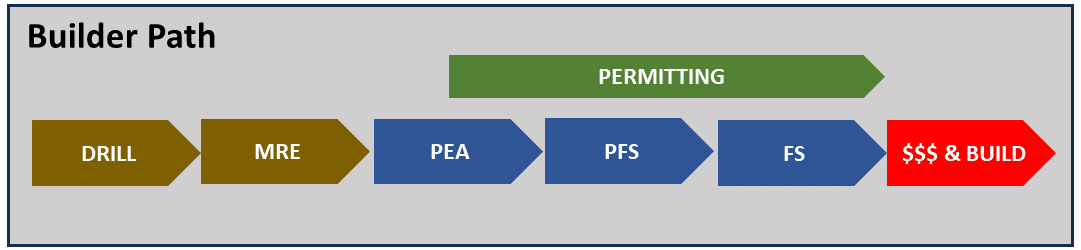

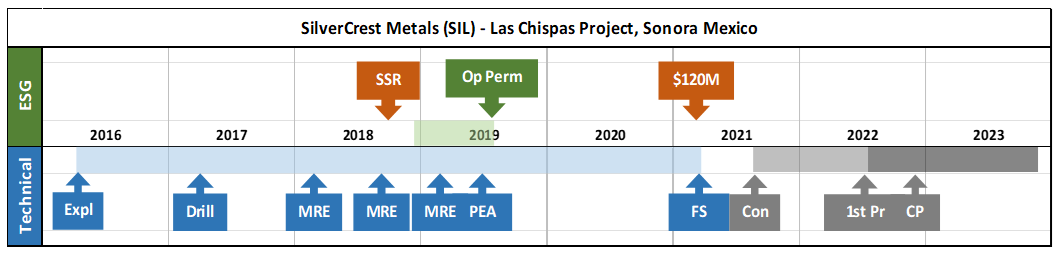

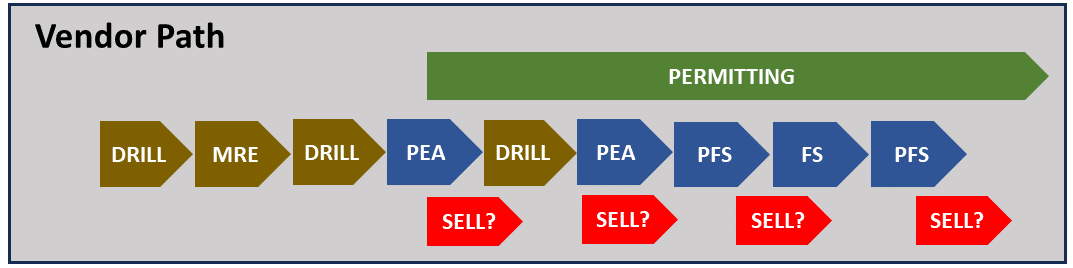

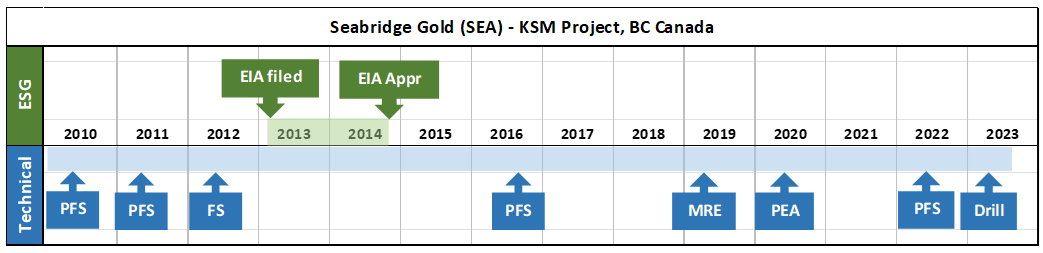

If an engineer understands that a Mine Builder’s project will move from PEA to PFS to FS in rapid succession, then there is more incentive to ensure each study is somewhat integrated.

If an engineer understands that a Mine Builder’s project will move from PEA to PFS to FS in rapid succession, then there is more incentive to ensure each study is somewhat integrated. As an engineer, it is helpful to understand the objectives of the project owner and then tailor the technical studies to meet those objectives. This does not mean low balling costs to make the study a promotional tool. It means focusing on what is important. It means recognizing the path, and what doesn’t need to be engineered in detail at this time. This may save the client time, money, and improve credibility in the long run.

As an engineer, it is helpful to understand the objectives of the project owner and then tailor the technical studies to meet those objectives. This does not mean low balling costs to make the study a promotional tool. It means focusing on what is important. It means recognizing the path, and what doesn’t need to be engineered in detail at this time. This may save the client time, money, and improve credibility in the long run. This post is just a brief discussion of mining project timelines. For those interested, there a few additional project timelines for curiosity purposes. Each path is unique because no two mining projects are the same. You can find these examples at this link “

This post is just a brief discussion of mining project timelines. For those interested, there a few additional project timelines for curiosity purposes. Each path is unique because no two mining projects are the same. You can find these examples at this link “

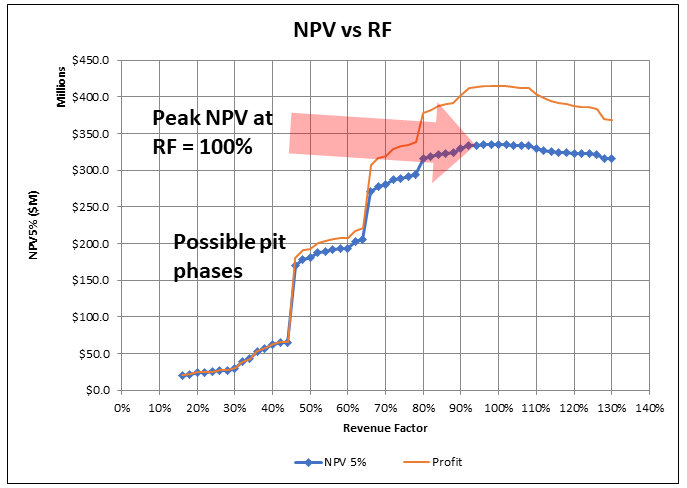

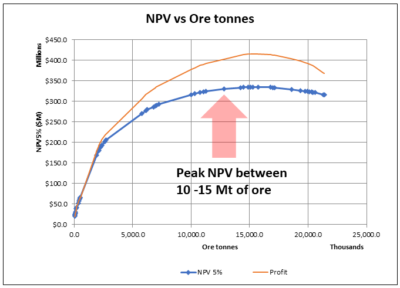

Often in 43-101 technical reports, when it comes to pit optimization, one is presented with the basic “NPV vs Revenue Factor (RF)” curve. That’s it.

Often in 43-101 technical reports, when it comes to pit optimization, one is presented with the basic “NPV vs Revenue Factor (RF)” curve. That’s it.

Pit optimization is a approximation process, as I outlined in a prior post titled “

Pit optimization is a approximation process, as I outlined in a prior post titled “

It’s always a good idea to drill down deeper into the optimization output data, even if you don’t intend to present that analysis in a final report. It will help develop an understanding of the nature of the orebody.

It’s always a good idea to drill down deeper into the optimization output data, even if you don’t intend to present that analysis in a final report. It will help develop an understanding of the nature of the orebody.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy.

While waiting for various third-party due diligences to be completed, the company continue to do exploration drilling. There were still a lot of untested showings on the property and geologists need to stay busy. With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation.

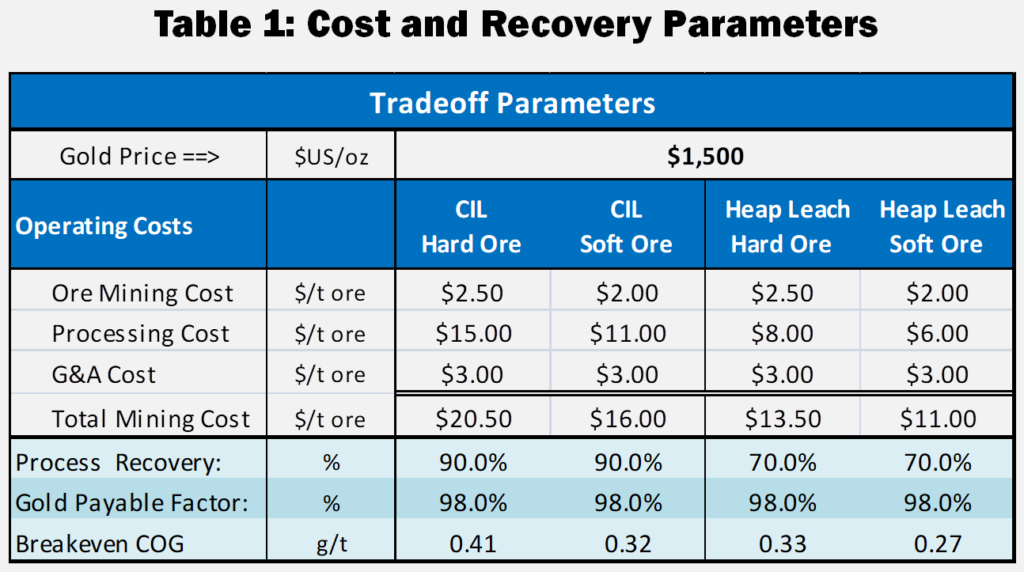

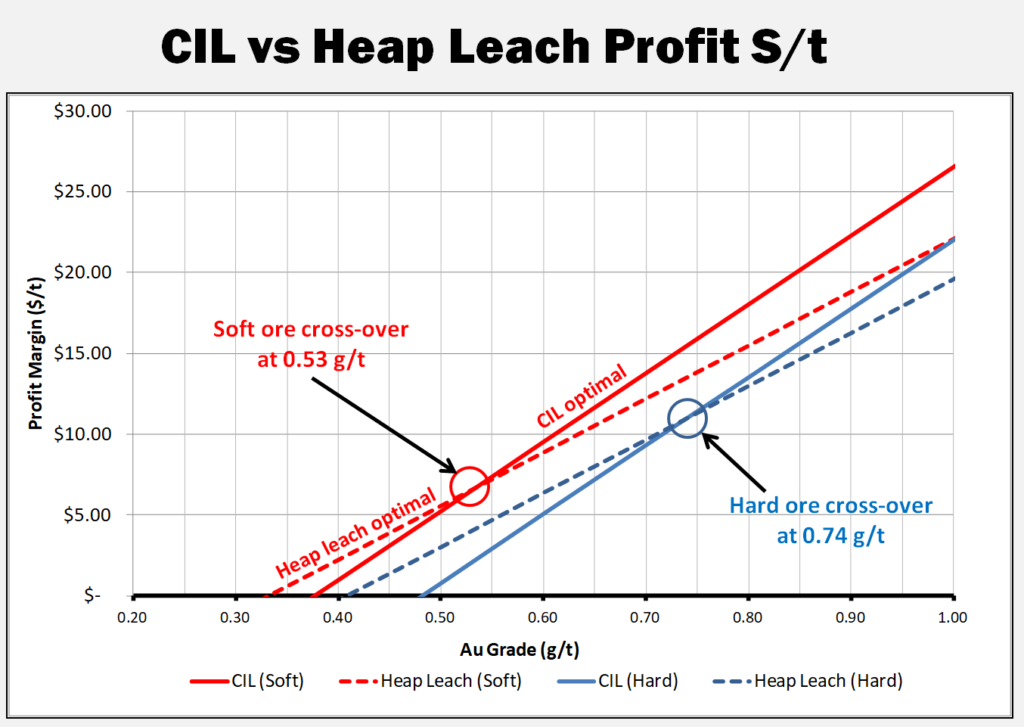

With regards to the Heap Leach PEA, we did not wish to complicate the Feasibility Study by adding a new feed supply to that plant from mixed CIL/HL pits. The heap leach project was therefore considered as a separate satellite operation. I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz.

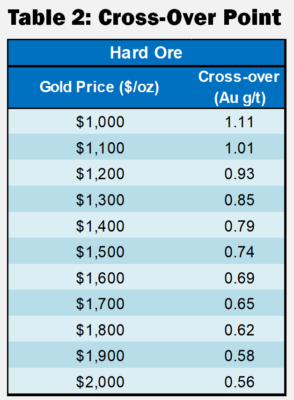

I have updated and simplified the trade-off analysis for this blog. Table 1 provides the costs and recoveries used herein, including increasing the gold price to $1500/oz. These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

These cross-over points described in Table 2 are relevant only for the costs shown in Table 1 and will be different for each project.

Perhaps with technology, like Zoom, one can replicate the personal feel of a trade show booth. One can still have back and forth conversations with investors rather than just doing lecture style webinars.

Perhaps with technology, like Zoom, one can replicate the personal feel of a trade show booth. One can still have back and forth conversations with investors rather than just doing lecture style webinars. Management teams should introduce more than just the CEO or COO. Include VP’s of geology, engineering, corporate development, from time to time. Don’t hesitate to let the public meet more of your team. Trade show booths are often manned by different team members.

Management teams should introduce more than just the CEO or COO. Include VP’s of geology, engineering, corporate development, from time to time. Don’t hesitate to let the public meet more of your team. Trade show booths are often manned by different team members. Better communication with investors can increase confidence in a management team. Although some investors may not enjoy technical discussions, I think there is a subset that will find them very helpful and interesting. There will likely be an audience out there.

Better communication with investors can increase confidence in a management team. Although some investors may not enjoy technical discussions, I think there is a subset that will find them very helpful and interesting. There will likely be an audience out there. As an aside, if you are using Zoom make sure the host has configured the right settings. There are instances where anonymous participants can suddenly share their own computer screen, i.e. with questionable videos, to the group. It’s been referred to as “zoom bombing”.

As an aside, if you are using Zoom make sure the host has configured the right settings. There are instances where anonymous participants can suddenly share their own computer screen, i.e. with questionable videos, to the group. It’s been referred to as “zoom bombing”.

On the site they have a searchable database for tax information for specific countries.

On the site they have a searchable database for tax information for specific countries.

Changes in economic parameters would impact the original pit optimization used to define the pit upon which everything is based.

Changes in economic parameters would impact the original pit optimization used to define the pit upon which everything is based.