In my view one thing lacking in the mining industry today is a consistent approach to quantifying and presenting the risks associated with mining projects. In a blog written in 2015 titled “Mining Cashflow Sensitivity Analyses – Be Careful” I discussed the limitations of the standard “spider graph” sensitivity analysis often seen in Section 22 of 43-101 reports.

This blog post expands on that discussion by describing a better approach. A six-year time gap between the two articles – no need to rush I guess.

This blog summarizes excerpts from an article written by a colleague that specializes in probabilistic financial analysis. That article is a result of conversations we had about the current methods of addressing risk in mining. The full article can be found at this link, however selected excerpts and graphs have been reprinted here with permission from the author.

The author is Lachlan Hughson, the Founder of 4-D Resources Advisory LLC. He has a 30-year career in the mining/metals and oil gas industry as an investment banker and a corporate executive. His website is here 4-D Resources Advisory LLC.

Excerpts from the article

Mining can be risky

“The natural resources industry, especially the finance function, tends to use a static, or single data estimate, approach to its planning, valuation and M&A models. This often fails to capture the dynamic interrelationships between the strategic, operational and financial variables of the business, especially commodity price volatility, over time.”

“A comprehensive financial model should correctly reflect the dynamic interplay of these fundamental variables over the company life and commodity price cycles. This requires enhancing the quality of key input variables and quantitatively defining how they interrelate and change depending on the strategy, operational focus and capital structure utilized by the company.”

“Given these critical limitations, a static modeling approach fundamentally reduces the decision making power of the results generated leading to unbalanced views as to the actual probabilities associated with expected outcomes. Equally, it creates an over-confident belief as to outcomes and eliminates the potential optionality of different courses of action as real options cannot be fully evaluated.”

Monte Carlo can be risky

“Fortunately, there is another financial modeling method – using Monte Carlo simulation – which generates more meaningful output data to enhance the company’s decision making process.”

Monte Carlo simulation is not new. For example @RISK has been available as an easy to use Excel add-in for decades. Crystal Ball does much the same thing.

“Dynamic, or probabilistic, modeling allows for far greater flexibility of input variables and their correlation, so they better reflect the operating reality, while generating an output which provides more insight than single data estimates of the output variable.”

“The dynamic approach gives the user an understanding of the likely output range (presented as a normal distribution here) and the probabilities associated with a particular output value. The static approach is relatively “random” as it is based on input assumptions that are often subject to biases and a poor understanding of their potential range vs. reality (i.e. +/- 10%, 20% vs. historical or projected data range).”

“In the case of a dynamic model, there is less scope for the biases (compensation, optionality, historic perspective, desire for optimal transaction outcome) that often impact the static, single data estimates modeling process. Additionally, it imposes a fiscal discipline on management as there is less scope to manipulate input data for desired outcomes (i.e. strategic misrepresentation), especially where strong correlations to historical data exist.”

“It encourages management to consider the likely range of outcomes, and probabilities and options, rather than being bound to/driven by achieving a specific outcome with no known probability. Equally, it introduces an “option” mindset to recognize and value real options as a key way to maintain/enhance company momentum over time.”

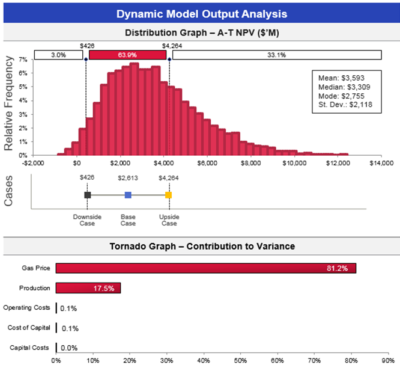

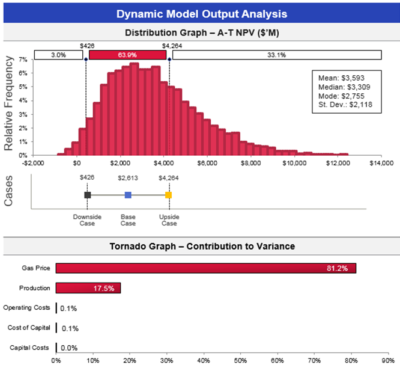

Image from the 4-D Resources article

“In the simple example (to the right), the financial model was more real-world through using input variables and correlation assumptions that reflect historical and projected reality rather than single data estimates that tend towards the most expected value.”

“Additionally, the output data provide greater insight into the variability of outcomes than the static model Downside, Base and Upside cases’ single data estimates did.”

The tornado diagram, shown below the histogram, essentially is another representation of the spider diagram information. ie.e which factors have the biggest impact.

“The dynamic data also facilitated the real option value of the asset in a manner a static model cannot. And the model took less time to build, with less internal relationships to create to make the output trustworthy, given input variables and correlation were set using the @RISK software options. This dynamic modeling approach can be used for all types of financial models.”

To read the full article, follow this link.

Conclusion

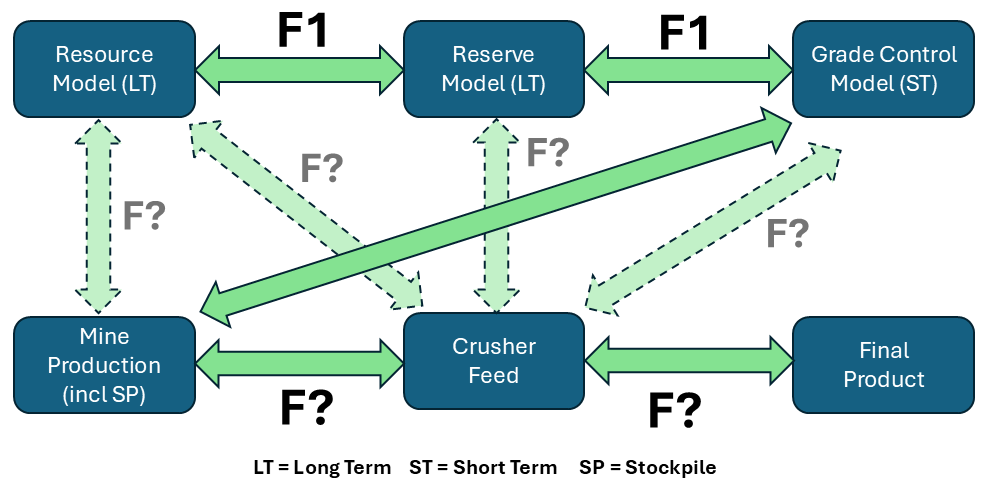

image from 4-D Resources article

Improvements are needed in the way risks are evaluated and explained to mining stakeholders. Improvements are required given increasing complexity in the risks impacting on decision making.

The probabilistic risk evaluation approach described above isn’t new and isn’t that complicated. In fact, it can be very intuitive when undertaken properly.

Probabilistic risk analysis isn’t something that should only be done within the inner sanctums of large mining companies. The approach should filter down to all mining studies and 43-101 reports.

It should ultimately become a best practice or standard part of all mining project economic analyses. The more often the approach is applied, the sooner people will become familiar (and comfortable) with it.

Mining projects can be risky, as demonstrated by the numerous ventures that have derailed. Yet recognition of this risk never seems to be brought to light beforehand.

Essentially all mining projects look the same to outsiders from a risk perspective, when in reality they are not. The mining industry should try to get better in explaining this.

Management understandably have a difficult task in making go/no-go decisions. Financial institutions have similar dilemmas when deciding on whether or not to finance a project. You can read that blog post at this link “Flawed Mining Projects – No Such Thing as Perfection“

Note: You can sign up for the KJK mailing list to get notified when new blogs are posted. Follow me on Twitter at @KJKLtd for updates.

The mining industry is implementing more and more technology in the mining cycle.

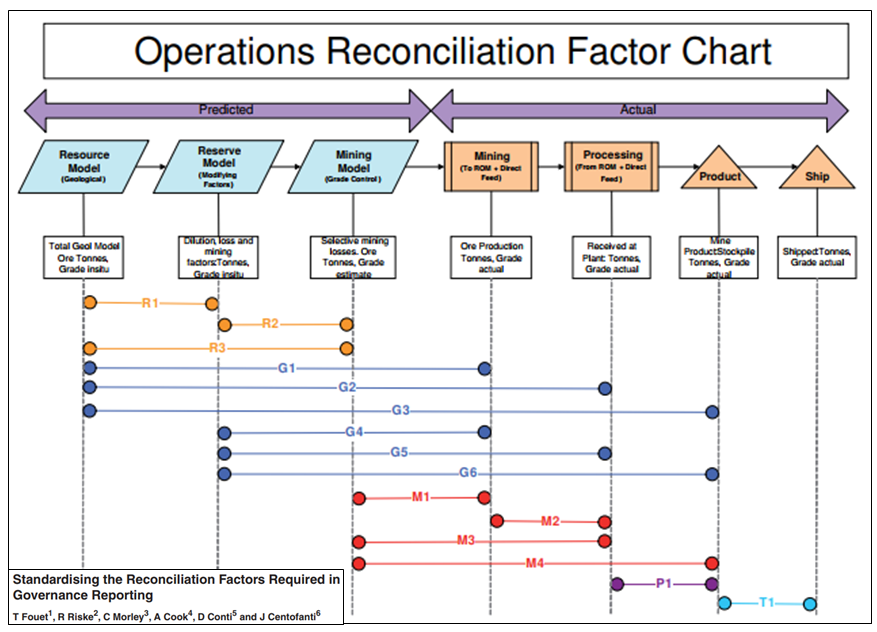

The mining industry is implementing more and more technology in the mining cycle. Mine reconciliation requires information such as initial predictions from exploration data and geological models, actual measurement: data from mining sources, such as blast holes, stockpile samples, or mill feed. As well it will need data on the final product being shipped off site. Do the metal quantities balance out throughout the mining operation?

Mine reconciliation requires information such as initial predictions from exploration data and geological models, actual measurement: data from mining sources, such as blast holes, stockpile samples, or mill feed. As well it will need data on the final product being shipped off site. Do the metal quantities balance out throughout the mining operation?

Each mine site may be unique with respect to; ore sources; terminology; ore types; mining methods; stockpiling philosophy; processing methods; technology availability; and personnel capability. So often the easiest approach for mine reconciliation is based on the Excel spreadsheet. (Reconciliation is generally not an easy undertaking).

Each mine site may be unique with respect to; ore sources; terminology; ore types; mining methods; stockpiling philosophy; processing methods; technology availability; and personnel capability. So often the easiest approach for mine reconciliation is based on the Excel spreadsheet. (Reconciliation is generally not an easy undertaking).

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some.

So, you just completed your initial PEA cashflow model and the resulting NPV and IRR are a little disappointing. They are not what everyone was expecting. They don’t meet the ideal targets of an IRR greater than 30% and an NPV that is more than 2x the initial capital cost. The project could now be on life support in the eyes of some. The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates.

The discounting of cashflows in a cashflow model means that up-front revenues and costs have a bigger impact on the final economics than those far off in the future. This effect is amplified at higher discount rates. ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen.

ake to the cashflow model. Sometimes several of the small ones, when compounded together, will result in a significant impact. Here are some of the other cashflow model adjustments that I have seen. Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Don’t let a disappointing NPV get you down. There may be a few ways to boost the NPV by applying some common practices. However, if after applying all of these adjustments, the NPV still isn’t great, something bigger may be required. That could be an entire project scope re-think.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times.

Two dilution approaches are common. One can either construct a diluted block model; or one can apply dilution afterwards in the production schedule. I have used both approaches at different times. Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant.

Sometimes lower grade stockpiles are built up by the mine each year but only processed at the end of the mine life. Periodically the ore mining rate may exceed the processing rate and other times it may be less. This is where the stockpile provides its service, smoothing the ore delivery to the plant. Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

Once the schedules are finalized, they are normally reviewed by the client for approval. The strip ratio and ore grade profile by date are of interest. One may then be asked to look to at different stockpiling approaches to see if an NPV (i.e. head grade) improvement is possible.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The last task for the mine engineer in Chapter 16 is estimating the open pit equipment fleet and manpower needs. The capital and operating costs for the mining operation will also be calculated as part of this work, but the costs are only presented in Chapter 21.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate.

The support equipment needs (dozers, graders, pickups, mechanics trucks, etc.) are typically fixed. For example, 2 graders per year regardless if the annual tonnages mined fluctuate. These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

These two blog posts hopefully give an overview of some of the things that mining engineers do as part of their jobs. Hopefully the posts also shed light on the amount of work that goes into Chapter 16 of a 43-101 report. While that chapter may not seem that long compared to some of the others, a lot of the effort is behind the scenes.

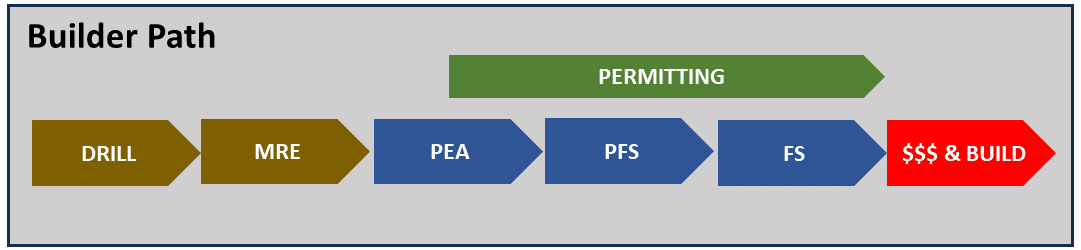

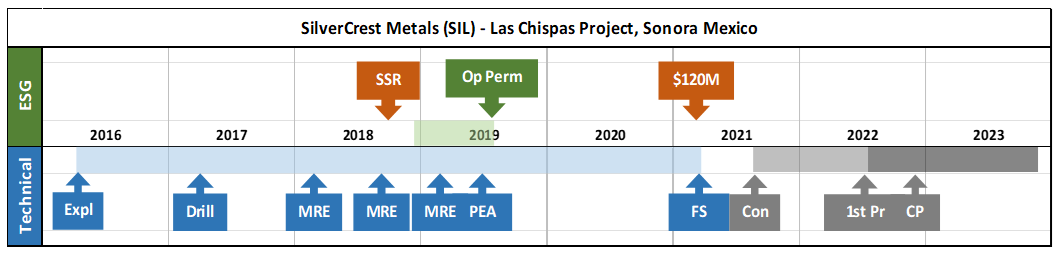

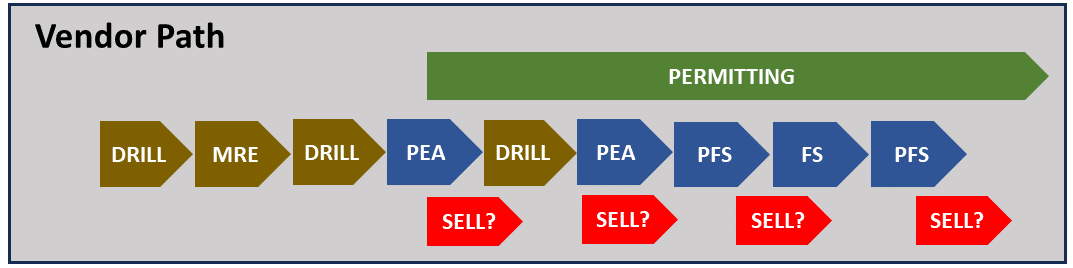

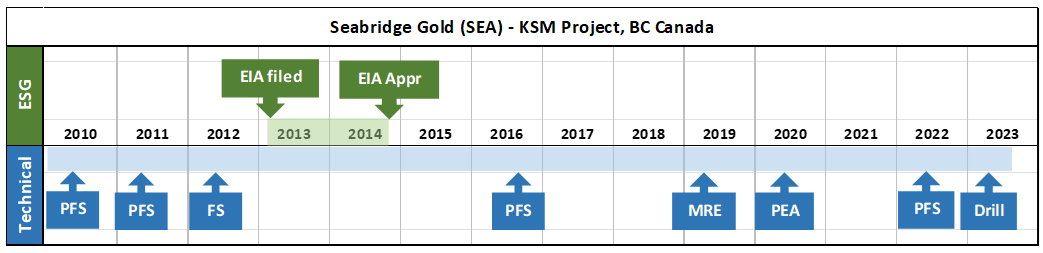

If an engineer understands that a Mine Builder’s project will move from PEA to PFS to FS in rapid succession, then there is more incentive to ensure each study is somewhat integrated.

If an engineer understands that a Mine Builder’s project will move from PEA to PFS to FS in rapid succession, then there is more incentive to ensure each study is somewhat integrated. As an engineer, it is helpful to understand the objectives of the project owner and then tailor the technical studies to meet those objectives. This does not mean low balling costs to make the study a promotional tool. It means focusing on what is important. It means recognizing the path, and what doesn’t need to be engineered in detail at this time. This may save the client time, money, and improve credibility in the long run.

As an engineer, it is helpful to understand the objectives of the project owner and then tailor the technical studies to meet those objectives. This does not mean low balling costs to make the study a promotional tool. It means focusing on what is important. It means recognizing the path, and what doesn’t need to be engineered in detail at this time. This may save the client time, money, and improve credibility in the long run. This post is just a brief discussion of mining project timelines. For those interested, there a few additional project timelines for curiosity purposes. Each path is unique because no two mining projects are the same. You can find these examples at this link “

This post is just a brief discussion of mining project timelines. For those interested, there a few additional project timelines for curiosity purposes. Each path is unique because no two mining projects are the same. You can find these examples at this link “

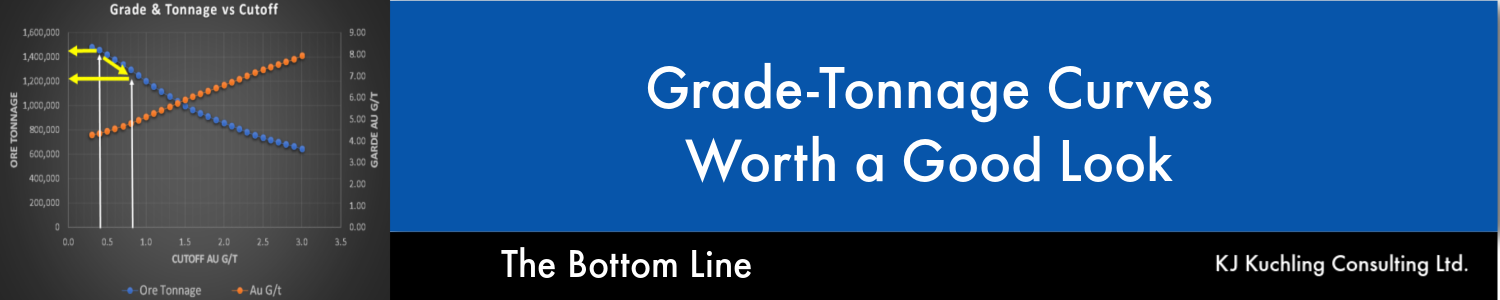

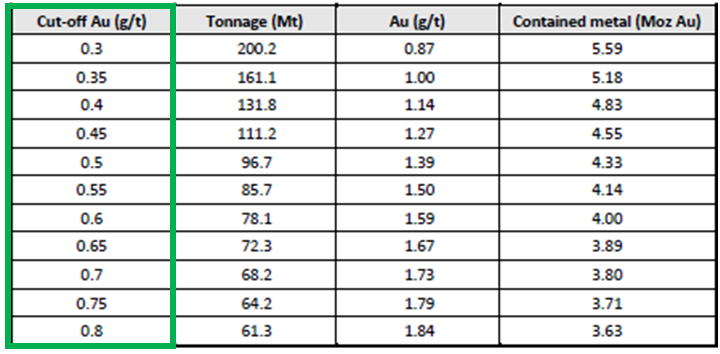

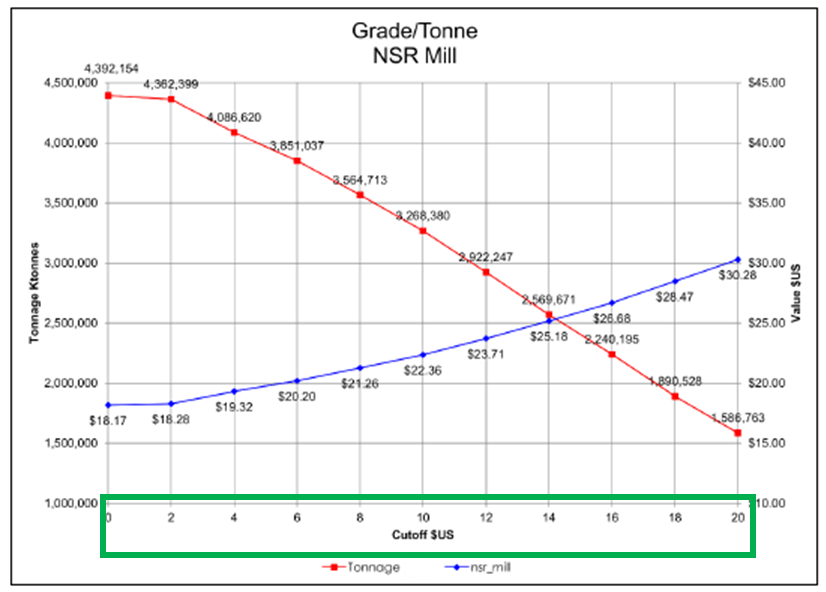

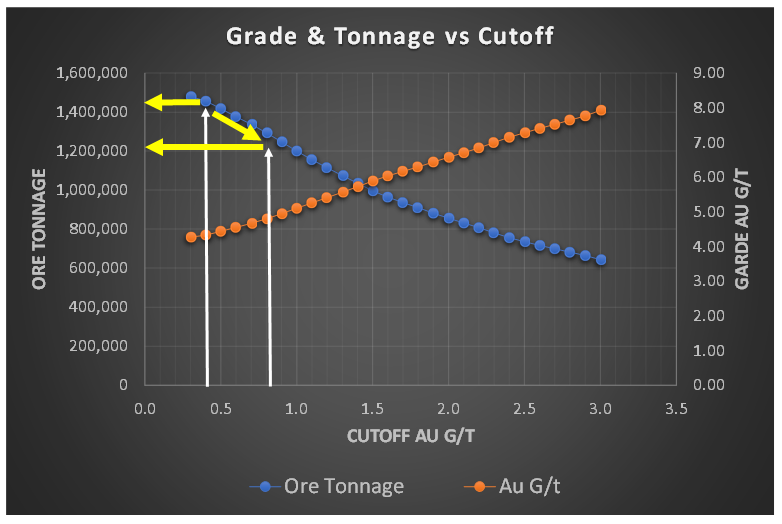

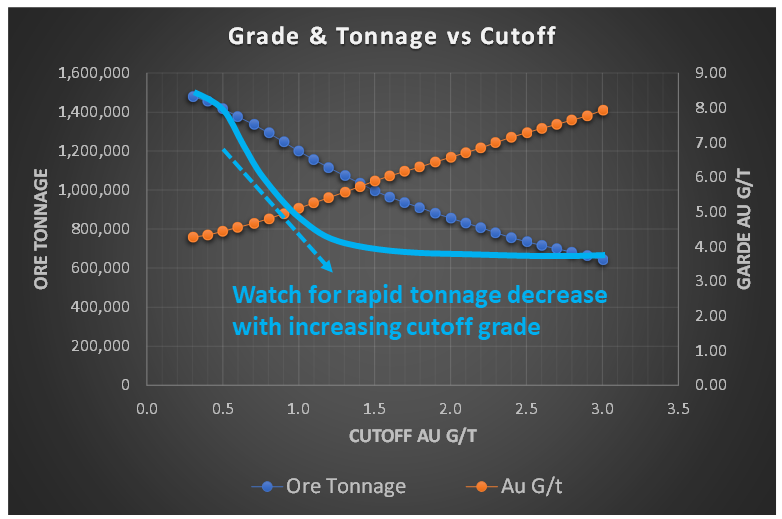

When I am undertaking a due diligence review or working on a study, very early on I like to have a look at the grade-tonnage information. This could be for the entire deposit resource, within a resource constraining shell, or in the pit design.

When I am undertaking a due diligence review or working on a study, very early on I like to have a look at the grade-tonnage information. This could be for the entire deposit resource, within a resource constraining shell, or in the pit design. However, if the tonnage curve profile resembled the light blue line in this image, with a concave shape, the ore tonnage is decreasing rapidly with increasing cutoff grade. This is generally not a favorable situation.

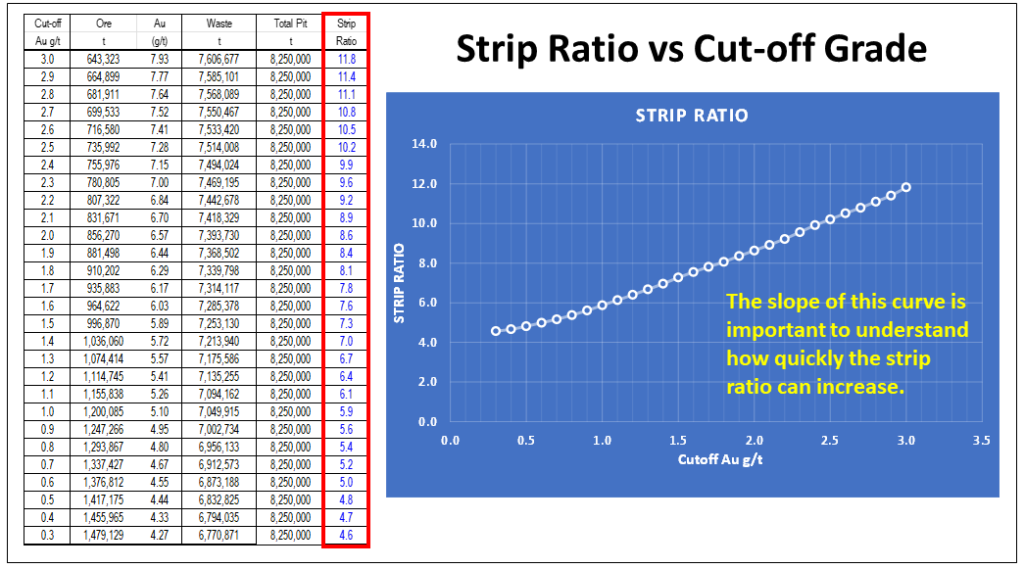

However, if the tonnage curve profile resembled the light blue line in this image, with a concave shape, the ore tonnage is decreasing rapidly with increasing cutoff grade. This is generally not a favorable situation. One complaint I have about reporting mineral resources inside a resource constraining shell is the lack of strip ratio information. This applies whether disclosing a single mineral resource estimate or variable grade-tonnage data.

One complaint I have about reporting mineral resources inside a resource constraining shell is the lack of strip ratio information. This applies whether disclosing a single mineral resource estimate or variable grade-tonnage data. Regarding mineral resources, one should be required to disclose the waste tonnage and strip ratio when reporting resources inside a constraining shell. The constraining shell and cutoff grade are both based on defined economic factors such as unit mining costs, processing cost, process recoveries, and metal prices. With respect to the mining cost component, the strip ratio is a key aspect of the total mining cost, yet it normally isn’t disclosed.

Regarding mineral resources, one should be required to disclose the waste tonnage and strip ratio when reporting resources inside a constraining shell. The constraining shell and cutoff grade are both based on defined economic factors such as unit mining costs, processing cost, process recoveries, and metal prices. With respect to the mining cost component, the strip ratio is a key aspect of the total mining cost, yet it normally isn’t disclosed. In 43-101 technical reports, the financial Chapter 22 normally presents the project sensitivities expressed in a spider diagram or a table format.

In 43-101 technical reports, the financial Chapter 22 normally presents the project sensitivities expressed in a spider diagram or a table format.

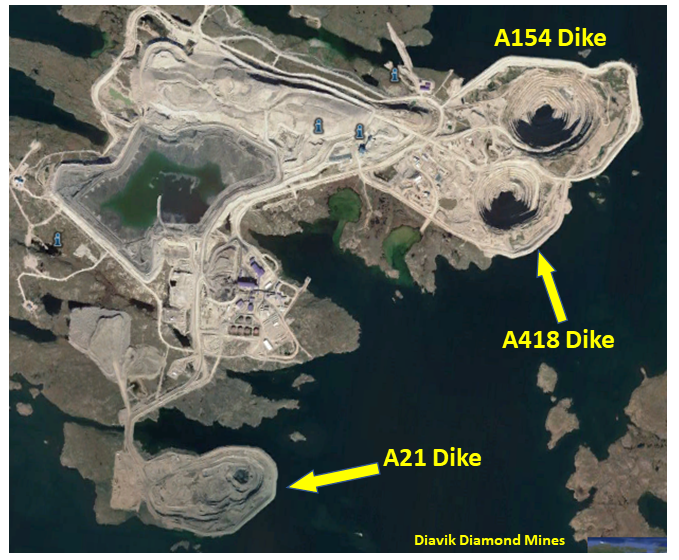

The primary question to be answered is whether one can mine safely and economically without creating significant impacts on the environment.

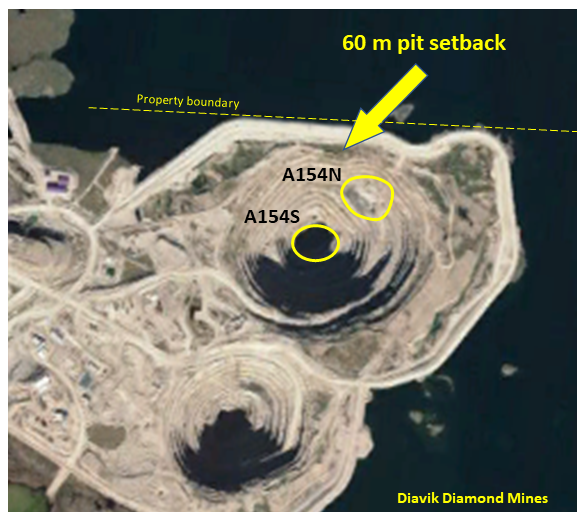

The primary question to be answered is whether one can mine safely and economically without creating significant impacts on the environment. Lake Turbidity: Dike construction will need to be done through the water column. Works such as dredging or dumping rock fill will create sediment plumes that can extend far beyond the dike. Is the area particularly sensitive to such turbidity disturbances, is there water current flow to carry away sediments?

Lake Turbidity: Dike construction will need to be done through the water column. Works such as dredging or dumping rock fill will create sediment plumes that can extend far beyond the dike. Is the area particularly sensitive to such turbidity disturbances, is there water current flow to carry away sediments? Pit wall setback: Given the size and depth of the open pit, how far must the dike be from the pit crest? Its nice to have 200 metre setback distance, but that may push the dike out into deeper water.

Pit wall setback: Given the size and depth of the open pit, how far must the dike be from the pit crest? Its nice to have 200 metre setback distance, but that may push the dike out into deeper water. Once the approximate location of the dike has been identified, the next step is to examine the design of the dike itself. Most of the issues to be considered relate to the geotechnical site conditions.

Once the approximate location of the dike has been identified, the next step is to examine the design of the dike itself. Most of the issues to be considered relate to the geotechnical site conditions. Each mine site is different, and that is what makes mining into water bodies a unique challenge. However many mine operators have done this successfully using various approaches to tackle the challenge.

Each mine site is different, and that is what makes mining into water bodies a unique challenge. However many mine operators have done this successfully using various approaches to tackle the challenge.

NPV One is targeting to replace the typical Excel based cashflow model with an online cloud model. It reminds me of personal income tax software, where one simply inputs the income and expense information, and then the software takes over doing all the calculations and outputting the result.

NPV One is targeting to replace the typical Excel based cashflow model with an online cloud model. It reminds me of personal income tax software, where one simply inputs the income and expense information, and then the software takes over doing all the calculations and outputting the result. Pros

Pros Like anything, nothing is perfect and NPV may have a few issues for me.

Like anything, nothing is perfect and NPV may have a few issues for me. The NPV One software is an option for those wishing to standardize or simplify their financial modelling.

The NPV One software is an option for those wishing to standardize or simplify their financial modelling.

We likely have all heard the statement that increasing pit wall angles will result in significant cost savings to the mining operation.

We likely have all heard the statement that increasing pit wall angles will result in significant cost savings to the mining operation. The results of applying the increased inter-ramp angle to each of the four pits is shown in the Bar Chart. Note that the waste reduction is not necessarily the same for each pit. It depends on the specific topography around each pit.

The results of applying the increased inter-ramp angle to each of the four pits is shown in the Bar Chart. Note that the waste reduction is not necessarily the same for each pit. It depends on the specific topography around each pit. In general one can typically see four positive outcomes from adopting steeper pit walls. They are as follows:

In general one can typically see four positive outcomes from adopting steeper pit walls. They are as follows: 4. Pit Crest Location: The steeper wall angles result in a shift in the final pit crest location. The Image shows the impact that the 5 degree steepening had on the crest location for one of the pits in this scenario.

4. Pit Crest Location: The steeper wall angles result in a shift in the final pit crest location. The Image shows the impact that the 5 degree steepening had on the crest location for one of the pits in this scenario. It is relatively easy to justify spending additional time and money on proper geotechnical investigations and geotechnical monitoring given the potential slope steepening benefits.

It is relatively easy to justify spending additional time and money on proper geotechnical investigations and geotechnical monitoring given the potential slope steepening benefits.

In today’s world, it is an onerous task to permit, finance, build, and operate a new mine. This is a significant achievement.

In today’s world, it is an onerous task to permit, finance, build, and operate a new mine. This is a significant achievement. I would suggest that the three reporting categories be used instead of two, described as follows:

I would suggest that the three reporting categories be used instead of two, described as follows: